The numbers that drove China’s Zero-COVID policy

At the beginning of the pandemic, several countries pursued a zero-COVID policy. Governments such as those in China, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand saw potential in an approach that focused all resources into total control and maximum suppression of the virus. Throughout 2021, as the rest of the world suffered from the rapid spread of emerging variants, people living in zero-COVID countries appeared to regain a large semblance of normal life.

Simultaneously, their COVID-related deaths were only a fraction of those experienced throughout the rest of the world. However, as more infectious but less deadly variants emerged, one-by-one those other countries had outbreaks of their own and were ultimately forced to abandon the policy. China, with its immense state resources and powerful social controls, maintained its zero-COVID approach.

Successfully controlling case numbers bred complacency. In 2022 other countries built capacity to manage the virus through robust vaccination campaigns targeting the elderly, new therapeutics and treatments, and rising natural immunity. In contrast, China’s own policy approach, such as the lockdown of its most populous city Shanghai, appeared increasingly chaotic and oppressive.

Zero-COVID has also become disastrous for the Chinese economy. For the first time since 1989, Beijing signaled it may miss its annual growth target of 5.5 percent, in part, because of its COVID restrictions. In recent days outraged citizens’ feelings transformed from waves of online anger into the largest protests China has seen in decades across Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and other cities and university campuses.

So why then has Beijing maintained its zero-COVID approach that has led to historic protests and a stifled economy?

Vaccinations

On its face, China has managed an incredibly successful vaccination campaign. As of November 11, 90 percent of China’s population had received two jabs, with 63 percent also receiving a booster. The United States has only fully vaccinated around 68 percent of its population with 34 percent also receiving a booster. China’s current vaccination rate is higher than any large nation when they began their respective openings. However, unlike other nations including the United States, China has been unable to encourage substantial vaccine uptake by its most vulnerable population groups, namely seniors.

China’s elderly population’s vaccination status remains the primary hurdle preventing a safe removal of the country’s COVID restrictions. While senior vaccination rates largely match the rest of the country, their booster status continues to lag. This is especially treacherous for Beijing as China resists the use of Western mRNA vaccines, the backbone to the US and European COVID health response. They instead rely on less effective, homegrown Chinese vaccines. As the chart below demonstrates, Chinese-made vaccines are only able to match the protection offered by mRNA vaccines such as the BioNTech-Pfizer vaccine in seniors after three doses. To prevent the surge of elderly deaths, China must roll out widespread booster campaigns to inoculate its seniors ahead of any reduction in its zero-COVID policies.

Beijing began taking steps to address this in late October. Regulators authorized the world’s first inhalable COVID vaccine which they hope will increase uptake among seniors with vaccination hesitancy. Following recent widespread protests, China has doubled down on these efforts and its top epidemic prevention body urged local governments to focus on getting the country’s elderly vaccinated against COVID. However, until China is able to get booster shots into the arms of its 254 million seniors, and particularly those older than eighty, Beijing risks a wave of deaths if it loosens restrictions.

Health care infrastructure

Even with an effective vaccination campaign, China’s health care system is not prepared to manage the inevitable nationwide COVID outbreak that will follow any easing of its strict COVID restrictions. Because of Beijing’s current approach, China has focused its resources on containment and failed to build the robust defenses needed to treat severe cases in a mass outbreak. Since early 2020 China has heavily invested in a colossal construction campaign to build field hospitals which are designed to house and treat mild and asymptomatic COVID cases. This stands in contrast to governments such as those of the United States and European Union which directed asymptomatic and mild cases to isolate at home, easing the burden on their health care systems, and focusing on building care infrastructure and treatment capacity for serious cases. Now, as protests force Beijing to begin pivoting towards reopening, the country’s health care system has been caught flat-footed.

China lacks both the treatment capacity and the personnel to handle an intense COVID surge. China has 3.1 nurses per one thousand people, below developing economy peers such as Brazil which have 7.4 nurses per one thousand people—and a far cry from developed nations like Germany which have fourteen nurses per one thousand people. China also lacks the critical care beds needed to treat a surge. Demand for intensive-care beds could reach fifteen times the current capacity during a surge according to a study published in May. While vaccination rates have improved since then, they are still not high enough to prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed.

China’s infrastructure deficit is further complicated by the country’s urban-rural divide. Rural areas have, on average, nearly 30 percent fewer doctors per one thousand people than China’s cities. They also still need major infrastructure investments as demonstrated by a $300 million loan the Asian Development Bank approved earlier this fall to improve public health services in poorer, rural regions in China after earlier waves of COVID exposed gaps in the state health system. Worryingly, the bank’s experts identify “admission surges that can negatively affect patient care and overburden facilities” as one of the motivating factors for the investment.

China may not be able to build the staffing and treatment capacity needed under the timeline Beijing may adhere to following widespread protests. But it could still turn to stockpiling antiviral drugs and therapeutics such as the drug Paxlovid to help manage a future COVID wave.

Towards a safer exit from zero-COVID

The coming winter will be the key test for Chinese policy makers. A late-November model suggests that if China were to lift strict restrictions now, Omicron could infect between one hundred and sixty million and two hundred and eighty million people—resulting in some 1.3 million to 2.1 million deaths, largely among unvaccinated seniors.

Despite this, Beijing seems resolved in shifting away from its zero-COVID approach. To do this safely, it should prioritize pragmatic preparations, otherwise it risks a large, deadly wave of COVID infections such as the one Hong Kong experienced in spring 2022. When Hong Kong began repealing its COVID restrictions it lacked a concrete plan for exit. Its infrastructure was woefully underprepared and the policy directions its government provided were outdated and unrealistic. For example, even at the peak of its outbreak, the city continued to isolate mild cases in hospitals, exacerbating capacity issues and leaving those with severe infections underserved leading to a spike in deaths.

Beijing has appeared to learn from the city state’s mistakes and taken some initial steps to facilitate a safer exit from zero-COVID. On December 6th the CCP announced new policies aimed at accelerating vaccination among the elderly as well as a nationwide expansion of rules that allow home isolation for asymptomatic and mild infections, already allowed in Beijing after its quarantine facilities ran out of space.

China should continue to prioritize the transition from preventing the spread of COVID towards the treatment of serious cases. Crucial areas to watch include Beijing’s ability to rollout an aggressive vaccination campaign focused on booster shots for vulnerable groups; the approval of new vaccines that either increase uptake or are more effective—such as China’s first homegrown mRNA vaccine; growth in China’s stockpile of COVID treatments; and updated guidance on the health risks of COVID and how hospitals and public health officials ought prioritize treatment. After 3 years of zero-COVID, a surge in cases may be inevitable but, through prudent policy and good preparations, a surge in deaths may still be avoided.

Niels Graham is an Assistant Director with the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center focusing on the Chinese economy.

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.

Further reading

Wed, May 11, 2022

China’s faltering “zero COVID” policy: Politics in command, economy in reverse

Report By Jeremy Mark, Michael Schuman

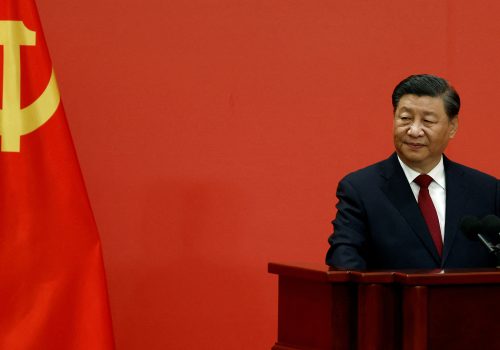

Could Beijing's doubling down on the "zero COVID" policy undermine the narrative of China’s superiority in responding to the pandemic—and the image and stature of Xi’s rule?

Mon, Nov 28, 2022

Experts react: What this wave of protests means for the future of the Chinese Communist Party

New Atlanticist By

How is the CCP likely to scramble to save face in the midst of rare protests—and will its efforts even work? Our experts give their takes on what the future holds.

Thu, Nov 10, 2022

Will Xi take a new economic direction? China has trillions at stake.

New Atlanticist By Niels Graham

Without reform, China's economy could be five trillion dollars smaller than projected by the end of the decade—with ramifications for global growth.

Image: Hong Kong - January 7, 2022 : People at a COVID-19 Mobile Vaccination Station receiving the BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine in Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon, Hong Kong. It enable people in the district, in particular elderly persons, to receive the BioNTech vaccine conveniently.