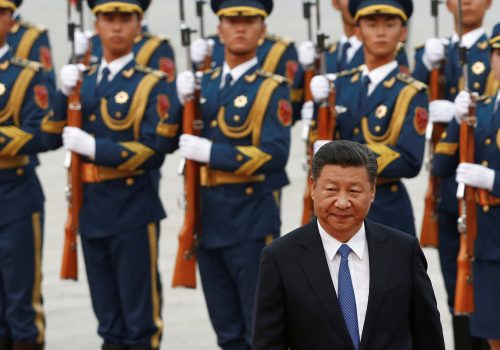

Is China facing another Tiananmen moment?

GET UP TO SPEED

They won’t be locked down. Protests against China’s zero-COVID policies have spread across the country, with some demonstrators even calling for Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping to step down. Today, police sought to more forcefully clamp down on protests in Beijing and Shanghai. How far could the protest movement go, what kind of threat does it pose to Xi’s government, and what should the world expect next? Our experts are on the case.

TODAY’S EXPERT REACTION COURTESY OF

- John Culver (@JohnCulver689): Nonresident senior fellow at the Global China Hub and former US national intelligence officer for East Asia

- Michael Schuman (@MichaelSchuman): Nonresident senior fellow at the Global China Hub and contributing writer for the Atlantic magazine

- David Shullman (@DaveShullman): Senior director of the Global China Hub and former US intelligence official focused on East Asia

Man in a box

- How did we get here? The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is “boxed in by its zero-COVID policy,” John tells us: It has tried to stamp out the spread of the disease with lockdowns and refused to import Western vaccines, and any change in course would be an unacceptable admission of defeat on those fronts.

- But staying the course has resulted in unrest from “the brave tip of the iceberg” of protesters, numbering mostly in the hundreds, John says. “In some ways, this is the situation for which Xi and his predecessor built the hardened party-state. But like even the biggest bank, they can’t survive a run in the form of major, persistent protests everywhere all the time.”

- It all adds up to “the greatest challenge to Xi’s power since he first claimed China’s helm a decade ago,” Michael says.

- The protests also undermine Xi’s claims that China’s COVID management “has demonstrated the effectiveness of China’s authoritarian system in comparison to democracy,” Dave says, “and more broadly put the lie to the argument frequently (and increasingly) repeated by Chinese officials that the Chinese people overwhelmingly approve of Party rule and its approach to governance.”

Subscribe to Fast Thinking email alerts

Sign up to receive rapid insight in your inbox from Atlantic Council experts on global events as they unfold.

Crack down and shake up

- A “practical course” for the CCP to pursue would be to carry out a “selective crackdown” now and ease it over time, John says. A date to watch is the Chinese New Year celebration in late January: “If they prevent travel on a large scale, their security nightmare will deepen, but travel could create superspreader events nationwide.”

- Michael points out that the measures announced so far to ease—or “optimize,” as the regime calls it—the zero-COVID policy are generally tweaks to the existing system, such as reductions in certain quarantine periods. “I think the government is going to have to introduce more fundamental changes to really make a difference,” he says. “As long as the pandemic strategy relies on arbitrary detentions and business closures, people’s lives and livelihoods will continue to face disruptions, and public discontent could continue to rise. Furthermore, as long as the leadership demands infections must be kept at or near zero, local officials will still feel pressured to take whatever steps they can to suppress the virus on their watch. And that means continued abuses.”

- In the videos of the protests that have leaked out so far, John sees only local police and health officials trying to quell the crowds—not the “huge anti-riot force” of the People’s Armed Police (PAP). “When we see the PAP in Beijing, Shanghai, or other major cities, that will demarcate an intensifying crisis.”

Shades of 1989

- While Dave cautions that the protest activity “does not mean we are witnessing the beginning of the end of the Communist Party,” he says a crackdown by internal security forces including the PAP “would likely set the groundwork for even more repressive policies across the board as the Party-state’s rule becomes more brittle and reliant on the threat of brute force and information control to maintain power.”

- We’re starting to see comparisons to the mass student protests of 1989 that led to leadership divisions in the Chinese government and the Tiananmen Square massacre. “If there’s going to be a major 1989-scale political crisis, it will have to start at the top, not from the grassroots,” John says, and there’s little appetite from elites to challenge Xi so soon after he solidified his power at the Party Congress in October.

- “But there’s a perfect storm potential where the regime relies on the stick, doesn’t provide hope or a plan to get out of zero-COVID hell, and protests spread, build, and are sustained,” John adds. He cautions, though, that it will be hard for those outside China to gauge any political splits in Beijing beyond assessing who shows up for major events or spotting criticism dribbling out from former top Chinese leaders.

- In such a scenario, the Chinese government could send in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), as it did during the Tiananmen massacre. “If you see the PLA rolling into cities, that means the regime is ready to kill people to stay in power, but their initial goal would be to avoid that by cowing” the public, John says. “No competent regime pushes their military, no matter how loyal, into repeated confrontations with the people—it’s a card they can only play a few times before the guns could start to swing the other way.”

Further reading

Wed, May 11, 2022

China’s faltering “zero COVID” policy: Politics in command, economy in reverse

Report By Jeremy Mark, Michael Schuman

Could Beijing's doubling down on the "zero COVID" policy undermine the narrative of China’s superiority in responding to the pandemic—and the image and stature of Xi’s rule?

Mon, Nov 14, 2022

What did Xi and Biden just accomplish?

Fast Thinking By

Our Sinologists read between the lines of the diplomat-speak following the US president and Chinese leader's meeting in Bali.

Tue, Oct 11, 2022

Your expert guide to China’s 20th Party Congress

New Atlanticist By

The once-in-five-years event is slated not only to further cement Xi Jinping's rule but also to have impact on a number of policy areas, from China's economy to its relationship with the Global South.

Image: People gather for a vigil and hold white sheets of paper in protest of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) restrictions, as they commemorate the victims of a fire in Urumqi, as outbreaks of the coronavirus disease continue in Beijing, China, November 27, 2022. REUTERS/Thomas Peter TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY