Geothermal: A “cool” heating resource

This piece is the second in a series examining geothermal potential in Iceland and elsewhere and the contribution geothermal resources can make to energy security and diversification, as well as sustainability and emissions reductions. You can read the first piece in the series here.

The first piece in this series focused on the development and benefits of geothermal utilization in Iceland, where geothermal resources are abundant and serve as the main source for home heating and roughly 30 percent of power production. In an area with regular volcanic activity, many would assume that geothermal potential is only to be found in areas like Iceland, where such geographical conditions are present.

However, that is not necessarily the case.

Especially not when it comes to low heat geothermal utilization, perfect for space heating and cooling. Actually, stable, secure, renewable, and domestic geothermal energy sources may closer than one might think, and could play a bigger role in the energy systems of the future, particularly in Europe.

When looking at building and strengthening twenty-first century energy systems in Central and Eastern Europe, especially with the aim of reducing CO2 emissions, increasing geothermal utilization for heating and cooling is both a practical and sensible option. In recent years, the European Union has put more emphasis on finding ways to reduce the use of fossil fuels in heating and cooling, by both improving and renovating old buildings, as well as increasing the use of renewable energy—a huge opportunity for geothermal.

In 2016, the heating and cooling sector accounted for 50 percent of the European Union (EU)’s annual energy consumption, with over 70 percent of the energy coming from non-renewable energy sources. Thus, it is clear that the task at hand is enormous. In the European heating and cooling mix, geothermal is grouped with “other renewables,” which together account for just 1.5 percent of the total energy mix.

According to an information hub about geothermal district heating in Europe, there are over 240 geothermal district heating systems operating around Europe. In comparison, there are around 5000 district heating systems in Europe which use other energy sources, mainly fossil fuel. Transforming these existing systems to geothermal where possible would benefit European countries, reducing CO2 emissions and helping them to meet their targets set in the Paris Agreement.

The good news is that geothermal awareness in Europe seems to be on the rise, with notable progress in the last five years according to the European Geothermal Energy Council’s 2018 geothermal declaration. The bad news is that this development is very slow. For a number of years, Iceland has worked hard within the European framework to get the EU to better incorporate geothermal energy in its energy policy, helping to increase EU interest in geothermal issues.

In 2017, it was announced that Iceland would lead an extensive European research program called GEOTHERMICA, a pooling of financial resources and expertise from eighteen geothermal energy research and innovation programs from fourteen European countries. This program follows the successful Geothermal ERA-NET program, which connected national and regional geothermal energy research programs together with the European Commission from 2012 to 2016. These programs are in accordance with the EU’s objective to increase the share of renewable energy for industrial purposes and for district heating and cooling, and they are an important acknowledgement of the future and potential role of geothermal in meeting Europe’s 2050 goals of mainstreaming renewable energy in the heating and cooling sector.

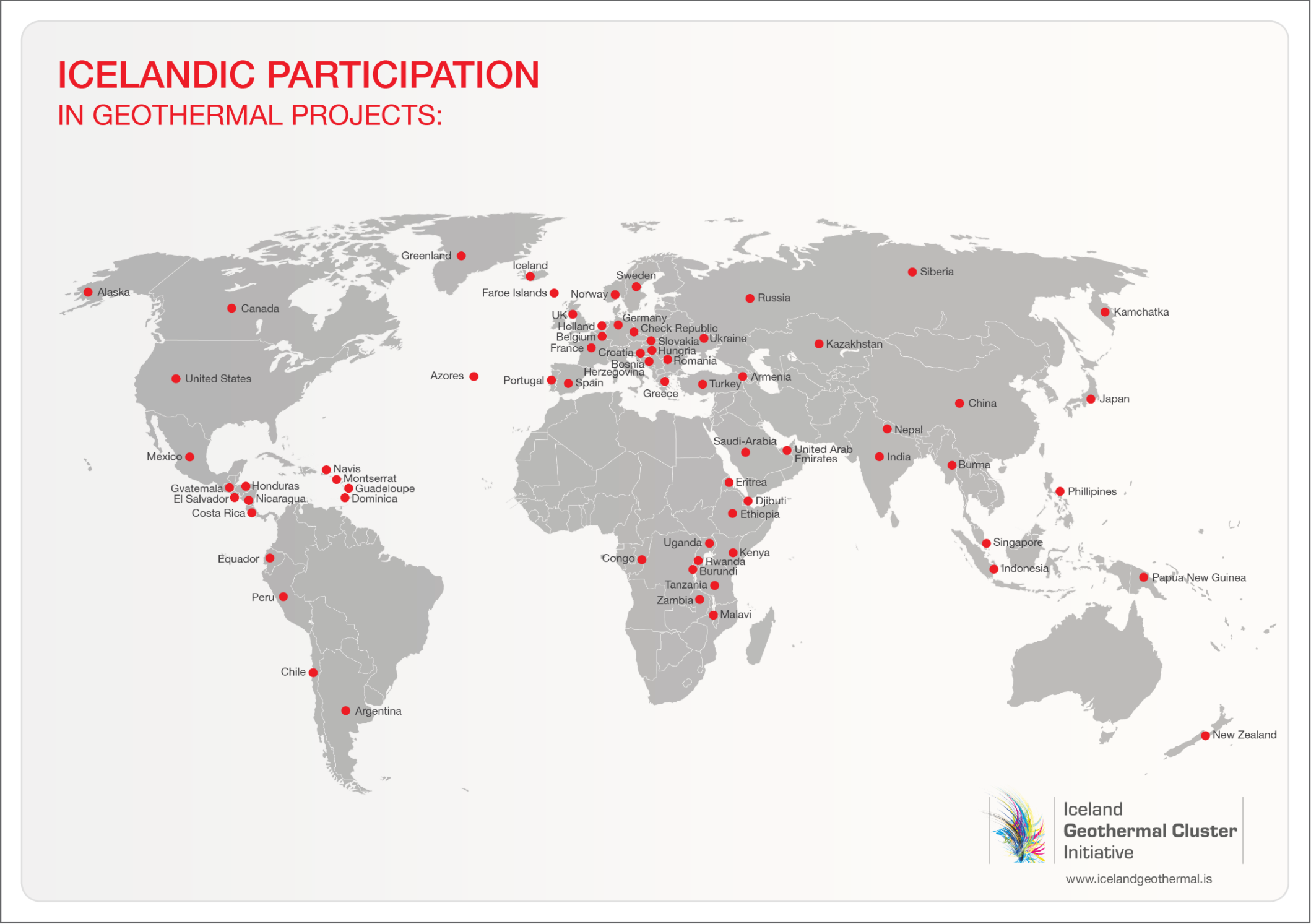

Geothermal energy is certainly not the only renewable energy resource, nor is Iceland the only country sustainably utilizing geothermal energy. However, Iceland has placed great emphasis on getting the geothermal message out by sharing its experiences and lessons learned. Fifty years’ worth of Icelandic experts’ experience have produced what could be called a new export industry, with Icelandic energy experts working on geothermal projects around the world (see Figure 1). These experts are working in all sectors of the geothermal industry, including research, consulting, design, and construction. A nonprofit industry driven geothermal cluster, the Iceland Geothermal Cluster Initiative, was established in 2013, with the goal that around fifty companies, associations, and institutions in the geothermal industry would cooperate with “increased competitiveness and increased value proposition.”

Figure 1. Icelandic Participation in Geothermal Projects

Source: Iceland Geothermal Cluster Initiative.

Along with Norway, Lichtenstein, and the European Union, Iceland is a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), through which it also promotes geothermal energy, namely geothermal district heating, and the potential for geothermal to significantly mitigate the EU’s demand for imported fossil fuels.

In cooperation with Norway and Liechtenstein, Iceland operates the EEA Grants funding facility, a financial mechanism in operation since 1994. The program, with estimated funding of €1.5 billion, is intended to reduce economic and social disparities in the EEA, benefitting the same states as the EU Cohesion Fund. Under the current Grant Scheme, Iceland has emphasized supporting renewable energy projects, particularly geothermal energy. The support has been used for feasibility studies, mapping of potential projects in different countries, research, and concrete projects, including a geothermal power plant in the Azores Islands and drilling activities and projects in Hungary, Romania, and Poland. Under this EEA scheme, studies have also been undertaken on the geothermal potential in Croatia.

These projects are an important demonstration of the benefits and untapped potential for utilizing geothermal for district heating in the world, not least in Europe, where district heating systems are already in place. To switch these systems where possible from imported, expensive, polluting energy sources to a local, stable, renewable one could, for example, be a huge step into the twenty-first century for energy systems in Central and Eastern Europe.

Ragnheiður Elín Árnadóttir is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. She served as Iceland’s minister of industry and commerce, and was responsible for energy issues. You can follow her on Twitter @REArnadottir

Image: Krafla geothermal power plant in Iceland (Photo by Ásgeir Eggertsson).