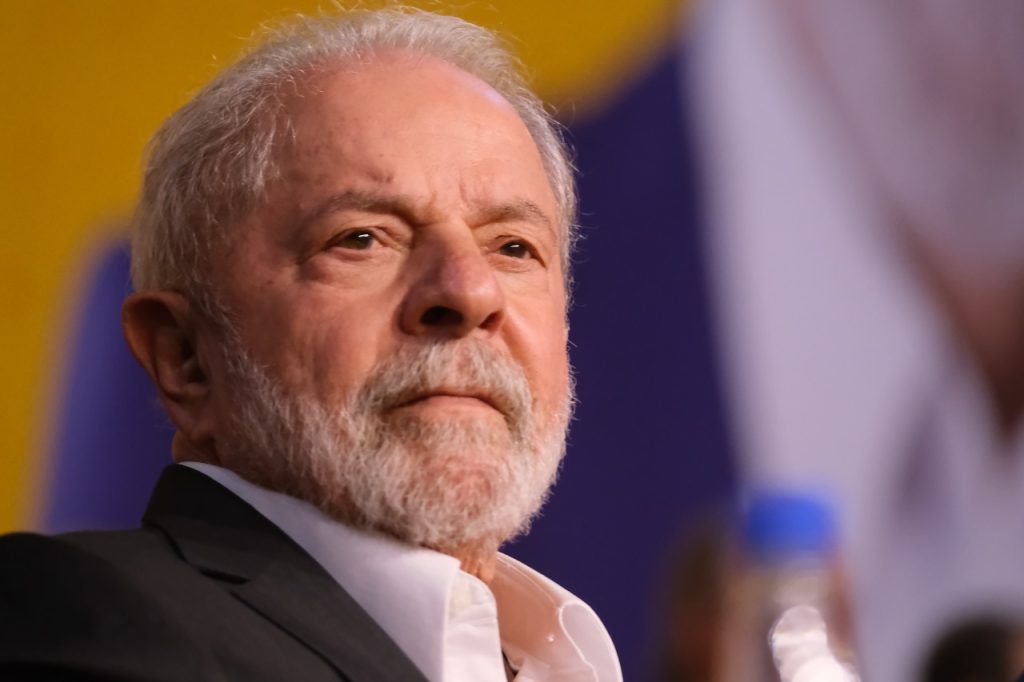

Following Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva’s presidential win in Brazil, Lula and President Biden met at the White House this month to set out a new agenda to further decarbonization and climate change efforts in the Western hemisphere. Early actions taken in Lula’s return to office show positive signals that Brazil is committed to implementing environmental and energy policies to address climate change while balancing economic development and environmental justice.

These actions are welcome, given the troubling environmental legacy of the prior administration. Deforestation rates surged under former President Jair Bolsonaro’s term, reaching the highest levels in 2021 since 2008. The Bolsonaro administration weakened environmental agencies intended to protect the Amazon rainforest, eased protections on protected land, and fired the head of Brazil’s National Institute for Space and Research (INPE) after it released data showing that deforestation rates had increased. Lax environmental policies resulted in land robbery and the increase of illegal activity, particularly related to logging and mining. Illegal mining saw a 46 percent increase in the Yanomami Indigenous territory in northern Brazil from 2020 to 2021, raising environmental justice concerns as the uniquely impacted Yanomami community experienced increased violence and diseases due to polluted rivers as a result of ore processing.

Lula’s return to office marks a return to the protection and conservation of the Amazon and its people while balancing the sustainable development of the region. The president created the country’s first Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, representing 307 indigenous groups. Lula also welcomed Marina Silva back to the federal government as Minister of Environment, the position she held during Lula’s first term as president. A well-known environmentalist from the Amazon state of Acre, Silva’s return to the Ministry signals Lula’s commitment to prioritizing environmental protection.

The return of the Amazon Fund

Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon has made the forest a net carbon emitter since 2016, accelerated by Bolsonaro’s policies and the shuttering of the Amazon Fund. Soon after Lula’s victory, however, Brazil’s Supreme Court ruled to reactivate the fund, which he signed on his first day back in office. With this reversal, Brazil is taking steps to once more be a clean energy and decarbonization leader in the region. But in order to reach these goals, expanding and diversifying funding is crucial.

Deforestation is a major factor in driving up greenhouse gas emissions, with tropical deforestation being responsible for roughly 20 percent of annual emissions. The Amazon rainforest holds 48 billion tons of carbon and its preservation is essential in the global fight against climate change and reaching ambitious net-zero goals. To assert low-carbon leadership in the region, Brazil should take advantage of the momentum behind the Amazon Fund right now.

The fund has historically been supported by Norway and Germany, but its support is set to grow. The Norwegian government—after backing out of the fund while Bolsonaro was in power—is keen on resuming donations immediately, and Germany signed a new pledge committing to donations following Lula’s October win. Additionally, following President Lula and Biden’s meeting this month, the two leaders released a joint statement in which Biden committed to work with the US Congress to contribute funds to conserve the Brazilian Amazon, including directly to the Amazon Fund. France, the European Union, and the United Kingdom have also announced their intentions to contribute to the fund.

While the addition of some of the world’s wealthiest countries are a significant step to broaden the fund’s scope, it is not enough. At COP27 in Glasgow, over one hundred world leaders representing more than 85 percent of the world’s forests pledged to halt deforestation by 2030, but little momentum has been seen since. As governments raise their ambition in forest preservation and funding, the focus must next turn to industry whose spending power and contributions in technology will be vital to expanding conservation efforts.

Private-sector participation in conservation funding would prove beneficial for Brazil, where although early satellite data shows deforestation in the Amazon has been declining since Lula’s return to office, experts say it may take years to show major progress following environmental setbacks under Bolsonaro. This progress will more effectively be accomplished with a suite of multi-sectoral funders. The fund’s potential for impact should be marketed to a broad coalition of funders from government, finance, and industry alike, with the option to contribute using verifiable carbon credits.

Building an even cleaner energy mix

Brazil’s environmental leadership need not be confined to the management of its ecosystems, however. Brazil already has one of the world’s highest shares of renewable energy in primary energy consumption, where clean energy sources meet 46 percent of total energy supply—not just electricity—in Brazil. By such a measure, Brazil is a clean energy powerhouse. Nonetheless, there are areas for Brazil to expand its low-carbon leadership.

Much of Brazil’s high share of clean energy in its energy supply is owed to biofuels, which are used in the industrial and residential heat, and transport sectors, at 50 percent and 25 percent, respectively. The country has been a pioneer in the use of biofuels for transportation, and in 2017 issued the RenovaBio policy which links the use of biofuels in transportation with Brazil’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement to reduce its emissions by 43 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. The country has committed under its NDC to increase the use of bioenergy, with high blending standards to support this. However, as an alternative to biofuels, Brazil could benefit from more targeted investment and policy support for electromobility, which does not pose the same concerns associated with the carbon intensity of land use. Brazil surpassed 100,000 cumulative electric vehicle sales in 2022, but deployment is limited by a lack of charging infrastructure. The country has less than 5,000 charging stations, while Germany, for instance, has over 1 million.

Furthermore, the country has a genuine opportunity to increase the share of clean energy in the power grid above 86 percent. Much of this share is owed to hydropower, which accounts for about 65 percent of total generation. Brazil is being eyed as a prime destination for wind development, with a potential of 1.8 terawatts (TW) onshore and offshore. The Ministry of Mines and Energy has taken steps to clarify the regulatory and legal frameworks for offshore wind development, which are severely lacking across Latin America, and could be catalytic for investment beyond the 17 GW of offshore wind already planned in Brazil.

However, the integration of intermittent renewables onto the electric grid will require more power system balancing to ensure generation matches demand. This comes amid a troubling outlook for hydropower in Brazil, historically a reliable baseload energy source, but whose generation is forecast to be more variable, as climate change leads to abnormal weather patterns. Increasingly frequent droughts and less predictable rainfall may increase the need for energy storage or gas peaker plants, if necessary, to ensure the consistent delivery of electricity to consumers.

Another area for Brazil to lead is by modernizing Petrobras and orienting it towards the energy transition. Petrobras is the largest oil company in Latin America and Brazil’s flagship state-owned enterprise. Prior to Lula’s victory, core energy advisors expressed a desire to make Petrobras more active in investing in renewable energy assets. After his election, Lula appointed Jean Paul Prates to the role of CEO, a senator and political ally of Lula. Prates has a history of introducing sustainability-focused legislation, even during Bolsonaro’s term. This background could bode well for the management of Petrobras at a critical juncture. Debt-constrained Petrobras will need to find innovative models if it desires to pair energy-transition ambitions with returns for the Brazilian public, but if it succeeds, it could offer lessons for national or state-owned oil company modernization on a global scale.

Bolstering Brazil’s environmental and clean energy leadership will require careful planning in the years ahead. The re-emergence of Lula does not seal this fate. While it can showcase its clean electricity sector, Brazil will need to balance using resources for conserving the Amazon and expanding electrification amid competing domestic economic and political priorities. For instance, Brazil will need to invest to maintain its social welfare state, amid a high benchmark interest rate of 13.75 percent and conflict between the Lula administration and the Central Bank of Brazil over fiscal policy, challenges which will impact the investment climate and Lula’s domestic political efficacy in tandem. Despite these challenges, Brazil has the potential to act as a first mover among emerging markets in making progress towards net-zero.

Lizi Bowen is associate director for digital communications and community engagement at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Maia Sparkman is an assistant director at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

William Tobin is a program assistant at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Meet the authors

Related content

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Lula. (Sergio Dutti, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en