On Saturday, President Joe Biden signed into law a bill that raises the debt limit in exchange for concessions on federal spending. The deal also seeks to reform permitting for energy projects by introducing changes to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), commissioning an interregional transfer capability determination study, streamlining approvals for energy storage projects, and—most controversially—completing the Mountain Valley Pipeline.

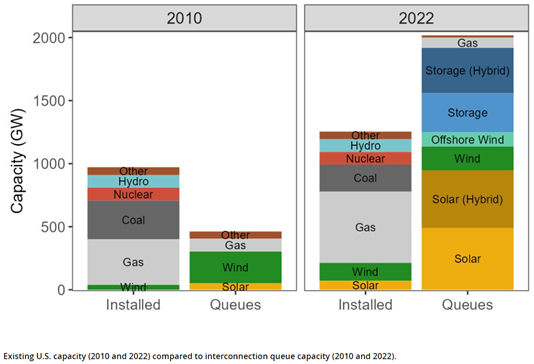

Shortening the review process for transmission projects and renewable interconnection to the grid is critical for accelerating the United States’ clean energy transition. Transmission lines take an average of five to ten years to build, largely due to the complex patchwork of stakeholders and permitting authorities involved in the review process. In addition, of the 2,000 gigawatts (GW) of generation capacity awaiting connection to the US transmission system, natural gas accounts for only 85 GW and coal merely 1 GW—the rest are zero-carbon technologies.

The critical permitting bottlenecks holding back the energy transition involve securing access to and approval of new transmission lines and the interconnection of new renewable projects to the grid. The legislation in the bill does not address either subject and will do little to clear the blockages in the permitting queue. To meet climate targets, legislators must adopt additional measures that are specific to transmission and renewable interconnection.

Completion of the Mountain Valley Pipeline

The Mountain Valley Pipeline, the most contentious of the provisions included in the bill, will proceed with development and could be completed as early as the end of this year. Some approve of the pipeline’s completion for its potential economic and energy security benefits, while others condemn its negative environmental impact. Construction on the pipeline is already 94 percent complete, but the impact on the environment and indigenous communities remains an open issue.

The Builder Act

The debt ceiling deal includes the Builder Act, which introduces reforms to NEPA that impose time limits on environmental reviews unless the project sponsor and agency agree to extend, designate a lead agency to coordinate federal project permitting, and allow project sponsors to conduct the NEPA study themselves, subject to agency review. In addition, the act revises language within the original NEPA legislation, requiring agencies to consider only environmental effects that are “reasonably foreseeable” and alternatives that are “technically and economically feasible,” potentially constraining which environmental impacts and alternatives a company must evaluate. Whether the updated legal language will result in a less comprehensive consideration of alternatives will be revealed in future litigation. Finally, the act shortens the length of NEPA documents, although the page limits do not apply to appendices, which could minimize the effects of this reform.

The provisions in the act that set time limits on the preparation of Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) and Environmental Assessments (EA) will shorten the federal review process but will not resolve the state and local jurisdictional issues that also hinder project deployment. Currently, it takes on average four-and-a-half years to complete an EIS. The Builder Act creates a two-year deadline for completing an EIS and a one-year deadline for an EA. The lead agency can extend the deadline in consultation with the project applicant but must complete the process within ninety days of a court order after the deadline. Projects, however, are not automatically approved if the timeline is not met, and significant barriers remain related to agency staffing to meet the shortened deadlines, an issue neglected in the debt ceiling reforms.

Contrary to widely expressed fears, these changes are unlikely to affect the integrity of the NEPA process. NEPA statements remain subject to the same judicial review as they were before the amendment, and if its conclusions are unsound, a reviewing court will send the NEPA document back to the agency for further review. The reviewing agency must still scrutinize any documents submitted by project sponsors and is responsible for final approval. If short deadlines prevent rigorous analysis from being completed, the NEPA document would not likely stand up in court. The environmental community, civil society, and businesses can still add comments or additional information to the administrative record but now have less time to review and comment on EISs and EAs, putting more pressure on interested parties to move swiftly.

Interregional Transmission Planning Opportunities Study

NEPA is not the biggest barrier to the rapid buildout of transmission and renewable infrastructure. The uncoordinated patchwork of federal and state permitting agencies involved in approvals, asynchronous review processes that stretch permitting times, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC)’s lack of direct authority over transmission wires—in contrast to its authority over natural gas pipelines—play a much more significant role in holding back project development. In addition, disagreements about cost allocation have proven formidable obstacles to building transmission and getting new renewable projects onto the grid.

These barriers are being studied extensively. The US Department of Energy (DOE) is conducting a National Transmission Planning study to be released this summer. FERC also issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NOPR) in April 2022 to improve regional transmission planning and cost allocation procedures. Instead of using these and other studies to inform legislation, the Builder Act directs the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) to conduct an interregional transmission planning opportunities study that will be published within eighteen months of the bill’s passage, followed by a year of public comment. FERC will then recommend statutory changes subject to their own review timeline.

Congress, FERC, and other federal agencies should not wait for completion of the NERC study. Instead, they should act using completed studies and the results of the DOE and FERC processes when considering additional transmission permitting and planning reform, as the infrastructure is needed as soon as possible. A Princeton study estimates the grid will need to expand by 60 percent by 2030 and triple in size by 2050. Building 60 percent more electricity transmission infrastructure within four years, starting in 2026 after the NERC study’s completion, is not feasible.

Permitting streamlining for energy storage

The bill also adds energy storage to the list of “covered projects” under the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act, which improves federal-state coordination and enshrines tangible deadlines for review, but can pose additional eligibility criteria and procedural requirements that do not make the process simpler. Project proponents are subject to restrictions on review period extensions and must interpret new terminology in consultation with agencies to ensure compliance with the program. Overall, including energy storage projects under FAST-41—named after Title 41 in the FAST Act—is a welcome development. Such programs should be expanded but must be supplemented with reform of the standard permitting process.

Recommendation for permitting reform

The permitting reforms in the agreed legislation will not affect the integrity of the EIS and EA processes, despite concerns from the environmental community. However, they fail to address the substantive permitting issues related to transmission and interconnection that investors and developers face today. Bills that address primarily oil and gas leasing and permitting are counterproductive to both the permitting discussion and energy transition goals. Legislators must work together and compromise to address permitting issues.

This article is the first in a series on EnergySource discussing permitting reform in the United States. The next article will examine opportunities for permitting reform after the debt ceiling bill.

Ken Berlin is a senior fellow and the director of the Financing and Achieving Cost Competitive Climate Solutions Project at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Frank Willey is a project assistant at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center.

Meet the authors

Learn more about the Global Energy Center

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Transmission pylons and wind turbines in the rural United States