Following the fraudulent outcome of Venezuela’s July election, calls are growing for the United States to reinstate maximum sanctions on the country’s oil sector. Critics of the regime of Nicolás Maduro want the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) to terminate licensing that allows US and European companies to operate within Venezuela’s petroleum industry.

But despite the fraught politics of the OFAC licensing system, Washington should stick with the current policy—which regulates cash flow into Venezuela, distances the country from China and Iran, and strengthens transatlantic energy security—rather than returning to the “maximum pressure” strategies that preceded it.

STAY CONNECTED

Sign up for PowerPlay, the Atlantic Council’s bimonthly newsletter keeping you up to date on all facets of the energy transition.

Maximum pressure, minimal results

In January 2019, the first Trump administration imposed broad sanctions on Venezuela’s state oil company, PDVSA, which expanded into a “maximum pressure” campaign that barred US oil companies from operating in the country and extended sanctions risk to non-US firms.

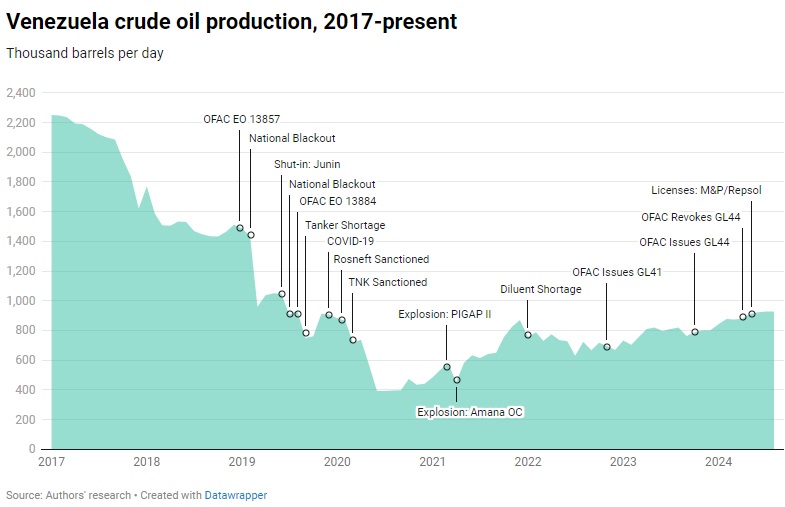

Stricter sanctions contributed to an abrupt decline in Venezuela’s crude oil production. Output crashed from 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd) in January 2019 to 430,000 by July 2020—although the effects of long-term underinvestment, national blackouts, and COVID-19 also impacted oil operations during this period.

The economic fallout from Venezuela’s oil bust intensified a wave of emigration that had begun in 2015. But the sanctions failed to dislodge Maduro—and polling, both internally and among the country’s diaspora, showed they were unpopular with most Venezuelans.

PDVSA quickly learned how to circumvent the sanctions. Secondary sanctions aimed at preventing companies from selling Venezuelan oil abroad were overcome through an extensive network of phantom traders.

As a result, by the end of 2020 China and Iran had emerged as Venezuela’s primary trading partners. Between July 2021 and July 2023, Venezuela imported over 35 million barrels of Iranian condensate as diluent used to produce 400,000-500,000 bpd of extra heavy crude oil. Over this two-year period, Iranian traders acquired over 47 million barrels of crude in exchange for that condensate, with nearly all shipments routed to China clandestinely and at steep discounts. These swaps circumvented sanctions and strengthened ties between Venezuela and Iran.

Course correction

Two years into the Biden administration the policy changed. In November 2022, OFAC issued General License (GL) 41 to Chevron, permitting it to resume operations under an agreement with PDVSA that allowed the US company to manage key aspects of its joint ventures, including procurement, crude marketing, and finance. Under GL41 and other specific licenses, Chevron can swap oil for US-sourced diluent. All production from joint ventures is required to be sold on the US market. Greater operational control has allowed Chevron to improve working conditions and mitigate safety and environmental risk.

In October 2023, GL44 lifted nearly all sanctions on PDVSA to induce the Maduro government to hold free and fair elections. However, the license was allowed to expire in April 2024 when the regime failed to recognize Maria Corina Machado or her designee as the opposition candidate in the presidential race. Instead, OFAC adopted a policy of issuing “specific” licenses to companies on a case-by-case basis for limited projects or activities.

Joint ventures operating in connection with specific licenses pay the Venezuelan government taxes and royalties in bolívars—not dollars—up to 50 percent of sales, as required by Venezuelan law. Payments to PDVSA are not allowed. Thirty percent of the value of each cargo is reinvested into operations and maintenance. The private partner manages this reinvestment, ensuring an additional layer of accountability. Funds are channeled to strictly vetted service companies.

Finally, 20 percent of each cargo is earmarked for the repayment of debt owed to the minority partner.

Detractors of the licensing regime express frustration with a lack of public information. OFAC licenses are diplomatic tools that permit certain economic activities within restrictions that result from challenging geopolitical conditions. Consequently, key information related to license activities is not made public. But “non-public” does not mean “opaque.” Detailed reports on all activities are filed with OFAC. Information on crude trades is available from numerous subscription sources.

Objectively, specific license holders do channel hundreds of millions of US dollars into the Venezuela economy through private banks. Many economists agree that the flow of these funds into the domestic economy plays a crucial role in stabilizing the exchange rate and managing inflation, which benefits all Venezuelans.

Better than the alternative

Given the unverifiable election results and subsequent human rights abuses in Venezuela, many question why the US government would authorize foreign oil operators to generate revenue from Venezuelan crude. The answer is that OFAC licenses are far more effective at regulating the cash flow from these sales than the maximum pressure sanctions of 2019 to 2022, when Western companies were divorced from their joint venture activities.

The issuance of specific licenses directed Venezuelan oil exports away from China and toward the United States, Europe, and India. In 2024, Venezuela exported 310,000 bpd to China, down from 491,000 in 2021. The share of oil exports marketed by phantom traders decreased from virtually all in 2021 to about 60 percent in 2024. Venezuela’s reliance on Iranian condensate ended, as OFAC-licensed companies are now allowed to import Western-sourced diluent for extra-heavy oil production.

If specific licenses are revoked, the consequences would not align with US energy and security interests, and may bring unintended costs for the opposition and the Venezuelan people.

PDVSA knows how to skirt maximum pressure sanctions and is well prepared to do so again. If those sanctions return, PDVSA would regain full discretion over revenue generated by approximately 300,000 bpd of crude exports, giving the Maduro regime direct access to more money than it currently receives—with no transparency requirements on how it uses it.

Crude sales would be diverted back to China from the United States, Europe, and India. Large discounts would effectively subsidize Chinese imports at the expense of Western company debt repayment. PDVSA would likely resume its reliance on Iran—instead of the US Gulf Coast—for diluent supply.

Venezuela accounts for just 1 percent of global oil production and has limited influence over oil prices. But with instability in the Middle East, it does no good to the United States to lose access to supplies so close to home. Removing Western companies from Venezuelan oil production would only increase energy security risks.

A fine line

Investors face a delicate balance in contemplating engagement with Venezuela, where human rights abuses and corruption pose real risks to moral integrity and financial viability. But the existing approach to OFAC licenses has found a productive middle path that provides greater economic stability, transparency, and control over the flow of revenue to the Maduro regime.

The United States remains limited in its ability to deliver a satisfactory political resolution in Venezuela. Although sanctions are historically ineffective at forcing regime change, they are likely to remain given Venezuela’s complex socio-political environment. But by retaining the existing system and avoiding a return to maximum pressure, the United States can act pragmatically to improve conditions for the Venezuelan people, support more effective mobilization for change, address global geopolitical priorities, and enhance transatlantic energy security.

David Voght and Patricia Ventura are experts on Latin American oil and gas markets and its energy transition.

The views expressed in this analysis are the authors’ own, based on independent research, and do not necessarily reflect those of any clients.

RELATED CONTENT

OUR WORK

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Oil drilling in Maracaibo Lake, Venezuela. (Breddyjgalvis, Wikimedia Commons). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atardecer_-_Lagunillas_-_Costa_Oriental_del_Lago_de_Maracaibo.JPG