Pretrial risk assessment tools must be directed toward an abolitionist vision

The Atlantic Council GeoTech Center seeks to provide public and private sector leaders insight into how technology and data can be used as tools for good. This publication examines the use of risk assessment tools in the United States criminal justice system. The analysis concludes that risk assessment tools must be framed as abolition technology if they are to address the systemic failures and oppressive practices of the criminal justice system.

The United States criminal justice system is increasingly turning to risk assessment tools in pretrial hearings—before a defendant is convicted of a crime—as well as in sentencing procedures. Risk assessment tools give judges a numerical metric that indicates a pretrial defendant’s risk of failing to appear in court, or threat to the community prior to their pretrial hearing. Judges set bail based on this tool. Facing an incredibly high volume of pretrial detainees, risk assessment tools are designed to help quickly and effectively determine pretrial detention and ease courts’ burdens. To truly address the failures of the criminal justice system, however, public sector leaders must:

- Utilize risk assessment tools as part of a broader effort to reducing the role of incarceration in American society;

- Account for the biases in crime data that stem the country’s racist history and the criminalization of historically marginalized communities; and

- Correct data and create the conditions for more accurate data that feed into the algorithms of risk assessment tools

Introduction

In today’s data-driven era, it was inevitable that algorithmic-based technology would be introduced into the deeply flawed US criminal justice system. Risk assessment tools have been hailed as a possible technocratic savior to protect the accused from the biased and unfair rulings made at the discretion of human judges, while also helping speed up pretrial detention decisions. Courts can use data-based risk assessment tools to make quick and supposedly unbiased decisions about pretrial bail and release. These algorithms use various data points including criminal history, socio-economic status, family background, and case characteristics to generate a score. This score is then provided to a judge to inform them of the likelihood that the defendant will appear for a future trial if released on bail. Based on the risk score, judges can grant and set bail amounts accordingly.

In the United States, incarceration takes the form of jails and prisons. Although specifics change based on jurisdiction, local law enforcement runs jails to hold people awaiting trial or people who have been convicted of a minor crime; prisons are for holding a person convicted of a serious crime, such as a federal offence, and are for serving a longer sentence. Approximately 70 percent of the US jail population is made up of pretrial detainees who have not yet been convicted. Many of these individuals must remain there awaiting trial because they are unable to afford cash bail—a practice that effectively criminalizes marginalized and impoverished communities and bloats United States’ jail populations. On average, pretrial detainees are incarcerated in jails for fifty to two hundred days before their trial. This is due to the sheer volume of pretrial detainees, who must wait for their day in court, and the limited capacity of courts themselves.

Proponents claim that risk assessment tools are one way to efficiently and effectively identify low-risk individuals who should not be in jail simply because they cannot post bail. Essentially, risk assessment tools are seen as a way to manage the large volume of pretrial detainees. Risk assessment tools are incorporated or mandated across the country in almost every state. Most recently, California’s Proposition 25 was drafted to replace cash bail with algorithms. Proposition 25, however, failed to pass after opposition by groups such as the NAACP and ACLU. The reason for the opposition was that risk assessment algorithms fail to reduce the volume of people who are arrested and may digitally replicate systemic and historic oppression by relying on data built through a history of criminalizing the black and brown body.

Overreliance on risk assessment tools turns them into prison technology. We define prison technology as existing and emerging technology that aims to disrupt the criminal justice system but ultimately ties new knots of the same inequality that underlies the foundations of the US criminal justice system that it attempts to correct. Investing in such reform actually diverts resources away from more critical reforms, exacerbating bias, unfairness, and inaccuracy in the system, all while maintaining the same levels of policing. While police officers and judges on the ground may try to resist the unjust practices of the criminal justice system, laws and policies in their current form perpetuate harm. As algorithms, risk assessment tools are designed to learn from these rules and their consequences using biased data collected by biased individuals working in an oppressive system. Risk assessment tools can help create a more just society, but only if they are reformed into abolition technology, which envisions the use and implementation of technology to reduce the role of incarceration and policing in the criminal justice system through alternatives that address the underlying causes of crime. If framed towards an abolitionist goal, risk assessment tools can help begin to create a justice system that is fair, effective, and rehabilitative.

Criminalizing America—risk assessment tools as prison technology

The criminal justice system must account for risk assessment tools’ substantial shortcomings before considering them and their underlying algorithms as technological saviors. Complex technology cannot solve age-old societal problems alone. These shortcomings turn risk assessment tools into prison technology. The Partnership on AI explains that “it is a serious misunderstanding to view tools as objective or neutral simply because they are based on data.” When considering the technical details and the human-computer interface of risk assessment tools, the Partnership on AI found three key types of challenges.

First, risk assessment tools are often invalid, inaccurate, or biased in predicting real world outcomes. For example, many algorithms are programmed to measure the likelihood of an individual incurring another arrest, not whether they are a threat to public safety. The tools are simply using the wrong metric. Additionally, algorithms are likely to reflect the existing biases and oppressive practices of over-policing and criminalization of historically marginalized communities. Second, risk assessment tools rely on judges and lawyers to understand how the prediction works and make fair interpretations. This means people in power must effectively interpret statistical information, confidence intervals, and error bands, and be well-versed in the uncertainty of the results. Third, risk assessment tools require effective governance, transparency, and accountability. Algorithms cannot exist behind a black box, but must be made accessible for public examination, debate, and ongoing regulation both inside and outside the courtroom by plaintiffs, defendants, and the general public.

Beyond the technical challenges, risk assessment tools have serious societal implications by continuing to criminalize historically marginalized communities. While this paper cannot go through all the communities who have been disproportionately policed, we particularly note a few including people of color, LGBTQ people, the poor, and the mentally ill. Risk assessment tools, as prison technology, simply automate the criminalization of these and other historically marginalized communities. Criminalization comes from a racist history that cannot be disentangled from the data fed into algorithms. As the Equal Justice Initiative notes, “today’s criminal justice crisis is rooted in our country’s history of racial injustice…and it’s legacy.” Unjust policing standards and the war on drugs evolved in direct response to the civil rights gains of Black, Indigenous, and communities of color to restrict their freedom. Consequently, these communities are intentionally and disproportionally stopped, searched, arrested, and charged, making them more likely to appear as high risk. Due to these practices, the input data for risk assessment tools is at the outset biased, only serving to reflect the racism in our criminal justice system.

This bias is rampant in the criminal justice system. One example can be found in the United States Department of Justice’s investigation of the Ferguson Police Department following the murder of Michael Brown in 2014. The Department of Justice found that officers see “those who live in Ferguson’s predominantly African-American neighborhoods, less as constituents to be protected than as potential offenders and sources of revenue.” Police were not interested in protecting the community: they were lining their coffers. Ferguson is not an isolated incident but instead representative of a broader culture of racism in the criminal justice system that is entrenched in the beliefs and actions of those who enact “justice.” In response to recent protests for racial justice North Carolina police officer and twenty-two-year veteran, Michael “Kevin” Piner, was recorded saying “We are just going to go out and start slaughtering them f—— n——…I can’t wait. God, I can’t wait.” A policing culture that fosters these types of sentiment cannot provide the unbiased and fair data necessary for risk assessment tools. This racism is built into the algorithms of risk assessment tools. In 2016, ProPublica found that COMPAS, a popular risk assessment tool used in Broward County, Florida, disproportionately categorized black defendants as high-risk, even when they did not go on to commit another crime. ProPublica’s study demonstrated how COMPAS was simply prison technology, ineffective at correcting the racist practices residing in our police departments while also upholding racism into its model.

While the criminal justice system has targeted communities of color, more broadly it unfairly punishes people facing poverty and mental illnesses. People experiencing homelessness are arrested for public intoxication, loitering, jaywalking, panhandling, or sleeping in public spaces, and almost all are unable to pay fines. Rather than receiving support, they are more severely policed and more likely to face conviction relative to white collar criminals, who are policed less, treated more leniently, and seen as “good people who made a mistake.” This means that people facing poverty who have committed nonviolent crimes are overrepresented in the data, which feeds into risk assessment tools outputs. This is despite the fact that the cost of white collar crime to the US economy stands at more than $300 billion. The policing of homeless people has also meant that LGBTQ youth are disproportionately targeted—LGBTQ youth make up 40 percent of the homeless youth population. Trans people are also particularly vulnerable, as they are incarcerated at twice the rate of cis people and experience high levels of mistreatment and sexual assault by the police.

Similarly, people with mental illnesses are simply more likely to be arrested and put in jail rather than receive medical treatment. For one, 20 to 25 percent of homeless people have at least one serious mental health issue. 20 percent of inmates in jail and 15 percent of inmates in prison have a serious mental illness—instead of being hospitalized, they are incarcerated and put into inhumane facilities that deny treatment, are overcrowded, and fail to punish rampant physical and sexual abuse by corrections officers. Today, approximately ten times more people are in jails and prisons for mental illnesses than in state hospitals. The result is a disproportionate number of people who are sentenced due to a mental illness, and a high recidivism and incarceration rate because the underlying mental health conditions are not dealt with in prisons. In the end, people with mental illnesses simply enter a never-ending cycle of incarceration, filling up prisons as their mental health is criminalized and untreated.

Other OECD countries with low incarceration rates do not rely on risk assessment tools

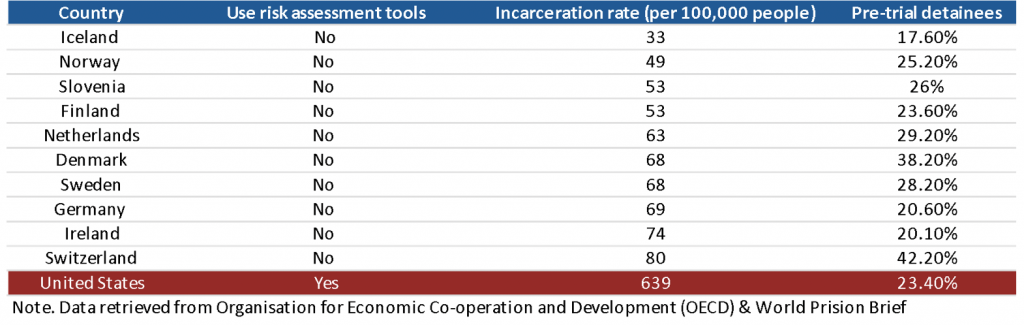

In the United States, risk assessment tools were envisioned to help manage the large number of pretrial detainees awaiting trial. The OECD countries with the lowest incarceration rates do not use risk assessment tools to determine pretrial detention. These OECD countries do not face the same volume of pretrial detainees because they have reduced the overall number of people in prison through alternatives to incarceration: low minimum sentences, emphasis on community service and supervision, and extensive social welfare programs. The OECD countries with the lowest levels of imprisonment have reduced crime by addressing its underlying causes and relying less on incarceration. Imprisonment is reserved for only certain crimes and even then, rehabilitation and reentry are emphasized to prevent recidivism. The result is a substantially lower incarceration rate than the United States’ despite a similar level of pretrial detainees—this solves the pretrial volume problem facing the United States criminal justice system. The table below details the ten OECD countries with the lowest incarceration rates plus the United States and whether they use pretrial risk assessment tools, their incarceration rate per 100,000 people using the national population, and the percent of people in prison and jail who are being held as pretrial detainees.

The United States has a similar rate of pretrial detainees to the other OECD countries, but about ten times the incarceration rate. The United States simply polices people more, locks up people at a higher rate after conviction, keeps them in prison for longer—the average prison sentence in the United States is three years—and creates conditions responsible for an unacceptably high level of recidivism. This is due to an emphasis on and inherent belief in policing and punishment. Prison conditions and relegation to a second-class citizen status without adequate resources for reentry contribute to the United States’ high recidivism rate. The United States Department of Justice found that 68 percent of people released in 2005 were rearrested within three years. On the other hand, Norway’s two-year recidivism rate is 20 percent , Finland’s is 36 percent, and the Netherlands’ is 35 percent. Risk assessment tools are meant to help manage this volume, but a better way may be to address the source of the volume: policing and criminalization.

Scandinavian countries focus less on policing and more on rehabilitation and alternatives to incarceration. This means fewer people entering the criminal justice system and of those who do enter, they leave with a lower likelihood of returning to prison. In Denmark, an emphasis on lower incarceration and no minimum sentencing requirements have enabled judges to assign volunteer hours or court-ordered supervision. To make these decisions, judges use pre-sentence reports, or ‘personal investigation reports,’ to consider a wide range of factors to determine risk. These factors include details such as childhood, employment status, mental health, and other personal or social problems that judges in the United States are not required to consider. In the United States, many people often fail to receive adequate counsel, resulting in sentencing by judges who do not account for other critical factors. Underlying the use of this information in Scandinavian countries is an emphasis on rehabilitation and justice, rather than retaliatory punishment. This is all grounded in a shared commitment held amongst elected officials, prison authorities, and civil servants to police less.

Germany prioritizes “normalization,” to make life in prison as close as possible to life in the community. The German Prison Act states that “the sole aim of incarceration is to enable prisoners to lead a life of social responsibility free of crime upon release.” This has meant resocialization to improve the reentry process and reduce recidivism. The German criminal justice system also employs alternatives to incarceration including fines, suspended sentences (similar to probation in the United States), and task penalties (work and training rehabilitation programs). Similarly, Iceland has implemented low minimum sentencing requirements and often uses electronic monitoring and community service. The European countries detailed above have kept incarceration and recidivism rates low. This is due to a commitment by politicians, judges, lawyers, and law enforcement officers to rely less on incarceration as a solution to the social problems resulting in crime. The United States can learn from these countries, rather than look to risk assessment tools as a way to manage the volume of pretrial detainees.

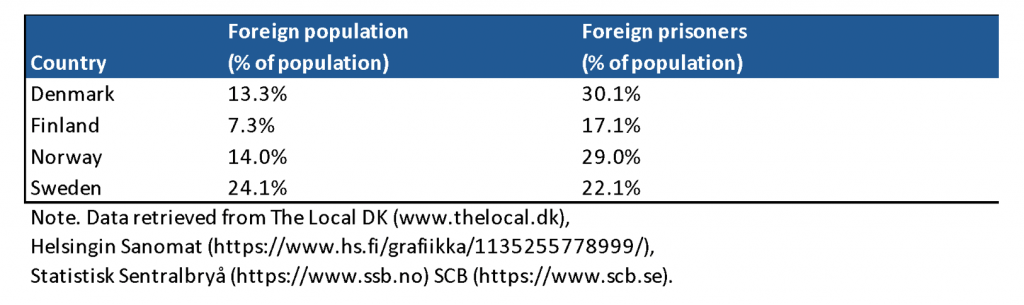

The United States, however, cannot look to Europe to solve the biases in its criminal justice system. In the United States, the black community makes up 13 percent of the population, but 40 percent of the prison population. The criminal justice system was designed largely to preserve a racial hierarchy. Similarly, Europe‘s colonial legacy and distrust of certain foreigners and ethnic minorities is represented by the people who are incarcerated there. In most Scandinavian countries, for example, people with a foreign background are overrepresented in prisons compared to the general national population.

Risk assessment tools in their current form as prison technology are ineffective because they fail to address the sheer volume of people who are incarcerated, and they operate on data that is biased against historically marginalized communities. Furthermore, the development and implementation of risk assessment tools may divert political and economic capital away from real criminal justice reform. Proposition 25, for example, was estimated to cost the public hundreds of millions of dollars a year to implement. Risk assessment tools in theory can reduce the number of pretrial detainees, but they do little to advocate for lower sentencing, alternatives to incarceration, racial justice, poverty alleviation programs, and drug and mental health treatment. The United States faces a unique set of challenges, which can only be solved by reckoning with its racist past and changing the country’s over-reliance on policing.

Transforming risk assessment tools into abolition technology

Data and technology must be used to uplift communities and break systems of oppression. In their current form, risk assessment tools utilize datasets built by unjust practices that historically marginalize communities, while retaining a white, heteronormative power structure. Scores only reflect the conditions in society today without solving underlying problems like over-policing, criminalization of communities, mental illness, and poverty. Risk assessment tools as abolition technology can do three things: divert people away from incarceration, create democratic mechanisms for the greater public and marginalized communities to influence how judges determine pretrial detainment, and make space to address unjust policing and the causes of recidivism.

First, risk assessment tools should be used with a commitment to limit incarceration. The underlying data used in risk assessment tools fail to accurately represent crime in America. Those developing risk assessment tools must assume this and require a high threshold for pretrial detainment. Risk assessment tools should only determine someone to be high risk if the evidence is overwhelming—and even here the data is likely to be biased. At the least, however, the number of errors might be reduced and judges encouraged to incarcerate less. Judges will have discretion on how risk assessment tools are used, so developers must require judges to override risk assessment tools and explicitly explain their reasoning if they decide someone poses a serious risk to society. This strategy allows for tech to play an important role in bail determination in a way that does not allow judges to hide behind algorithms as they set high levels of bail, while also potentially reducing incarceration. Additionally, risk assessment tools cannot serve as a primary source of decision-making but must instead be a secondary tool that informs judges. The Center for Court Innovation, for example, found that if a judge uses a moderate-high and high-risk threshold algorithm as a secondary tool for defendants charged with a violent felony or domestic violence offence, they reduced overall pre-trial detention and almost eliminated pre-trial detention biases against Black and Hispanic defendants.. In comparison, reliance on only judicial discretion or a high-risk threshold risk assessment tool resulted in both higher levels of detainment and greater levels of bias against Black and Hispanic defendants. Racial biases and incarceration levels were highest when decisions were made primarily through judicial discretion.

Second, open design frameworks are needed to ensure that the data being used is approved by the general public. Arrested people fail to receive adequate legal counsel far too often and must navigate a Kafkaesque legal system. In this case, risk assessment tools can be weaponized to simply serve as another inaccurate and unfair justification for incarceration. Risk assessment tools with open design approaches, however, give an opportunity for greater public involvement and awareness, and they can allow democratic mechanisms to make corrections to the data and change the way judges make decisions. Today, we are able to measure biases in data, as demonstrated by ProPublica in Florida. This means the underlying data can be adjusted, certain egregiously biased datasets removed (e.g. income), and models tweaked in order to reflect a fairer system—all that requires the technical examination of the data and output grounded in an understanding of the systemic issues at play and how they manifest themselves in the data. Critical for this process, however, will be ensuring that the communities most impacted by unjust policing have a substantial voice in the development and implementation of the risk assessment tool. Otherwise, open design frameworks will only continue the tradition of ignoring the voices of historically marginalized communities.

Third, risk assessment tools should not divert resources away from broader criminal justice reform. While risk assessment tools will need funding if they are to be improved, they will be largely ineffective unless more money and resources are directed towards transforming the system into one that is more just. Risk assessment tools cannot be used as an alternative to solving the problems of an unjust system that results in long sentences and recidivism. Along with being morally repugnant, the cycle of recidivism is expensive, and states have limited budgets. Approximately 25 percent of people entered prison in 2017 because of technical probation or parole violations, and a disproportionate number of them were people of color. Risk assessment tools will not solve this problem, the fact that people with mental illnesses are often arrested rather than admitted to hospitals, nor the lack of adequate counsel for people with little financial resources. Instead, risk assessment tools as abolition technology must be used as part and parcel of broader criminal justice reform enacted by states and the federal government.

A more just system based on good technology

Technological innovation should be used to challenge existing power structures to make a more equitable and just society. Risk assessment tools, if directed with an abolitionist vision, can help challenge the status quo of a criminal justice system that relies on incarceration and is predicated on a legacy of racial injustice. Risk assessment tools must be linked together with other initiatives and developed in partnership with the communities most affected. In order to do this, politicians, judges, lawyers, developers, and the public must:

- Reduce the role of incarceration by changing minimum sentencing requirements, utilizing alternatives to incarceration, and emphasizing rehabilitation over punishment;

- Refrain from considering data a savior given its bias against historically marginalized communities; and

- Create the conditions for more accurate data collection by addressing the underlying causes of crime through social welfare programs and the dismantling of oppressive institutions (e.g. laws, policing, business practices).

American leaders and the public must take responsibility for how risk assessment tools are used. An active commitment backed by political and economic capital to help the most marginalized and forgotten is needed. This is no easy task, but true criminal justice reform asks for nothing less.

Hannah Biggs is currently a consultant at the Atlantic Council GeoTech Center where she focuses on researching international innovations in data and technology to promote peace and prosperity. She has held multiple research assistant roles at organizations like the National Criminal Justice Association (NCJA) and Starting Over, and has therefore been able to focus on a diverse portfolio of topics at the state, federal, and international levels. She is passionate about economic development in low and middle-class economies, ethical governance and accountability, and creating equitable and just societies.

The GeoTech Center champions positive paths forward that societies can pursue to ensure new technologies and data empower people, prosperity, and peace.