We can build an immune system for the planet

Back in 2013 and again in 2016, a proposal informed by the anthrax events of 2001, West Nile Virus in 2002, and both Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and a outbreak of monkeypox in the United States in 2003 was shared with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The proposal at the time was something seen as a safeguard against a “low probability, high consequence” event – a natural or human-caused pandemic.

The solution was a series of proposals centered around the concept of building an “immune system for the planet” that could detect a novel pathogen in the air, water, or soil of the Earth and rapidly sequence its DNA or RNA. Once sequenced, high-performance computers would strive to identify both the three-dimensional protein surfaces of either the virus or bacteria and then search through an index of known molecular therapies that might be able to neutralize the pathogen.

At a minimum, such an immune system for the planet would overcome the limits of waiting for nation-states themselves to alert the international community of outbreaks within their borders.

A second reason also was associated with this proposal, namely: exponential changes in technology and create pressures for representative democracies, republics, and other forms of deliberative governments to keep up – both at home and abroad.

In an era in which precision medicine will be possible, so too will be precision poison, tailored and at a distance. As proposed both in 2013 and again in 2016: this will become a national security issue if we don’t figure out how to better use technology to do the work of deliberative governance at the necessary speed needed to keep up with threats associated with pandemics.

Building an immune system for the planet now

While the pitches to DARPA in 2013 and 2016 were not funded at the time; such a solution remains viable and now potentially even more possible to start in the next two to five years given advances in computing, biosensors, and our understanding of microbiology.

The premise of such a solution centers around the recognition that, per the 2001 anthrax events, SARS, H1N1, the biggest threat of biological agents is the protracted time window it takes to characterize, develop treatment, and perform remediation. We certainly are seeing this again with the current COVID-19 pandemic.

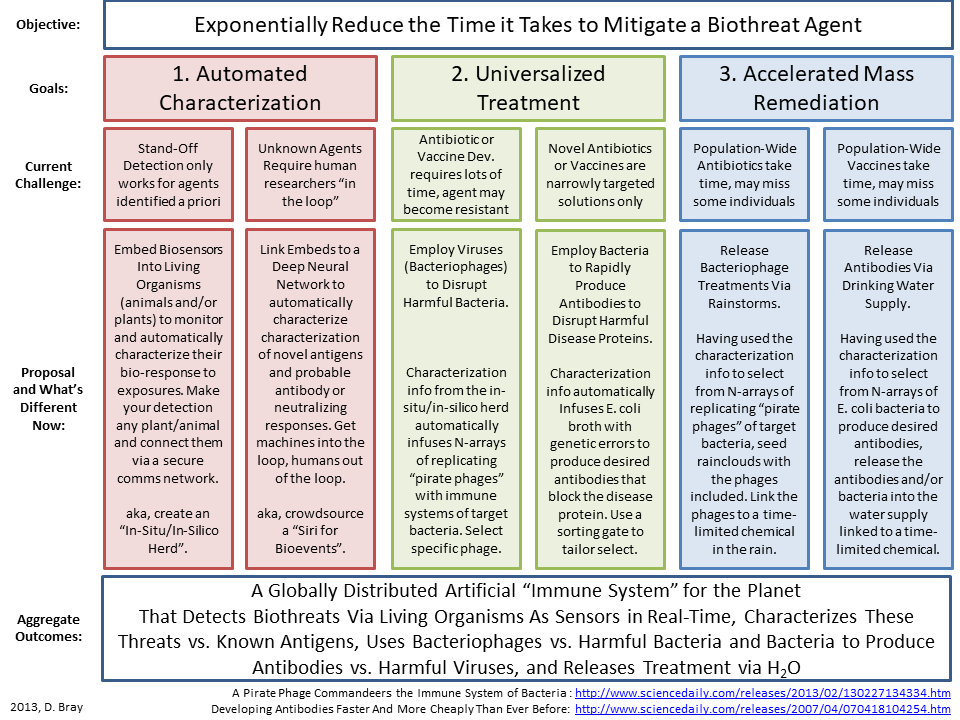

Exponentially reducing the time it takes to mitigate a biothreat agent will save lives, property, and national economies. To do this, we need to:

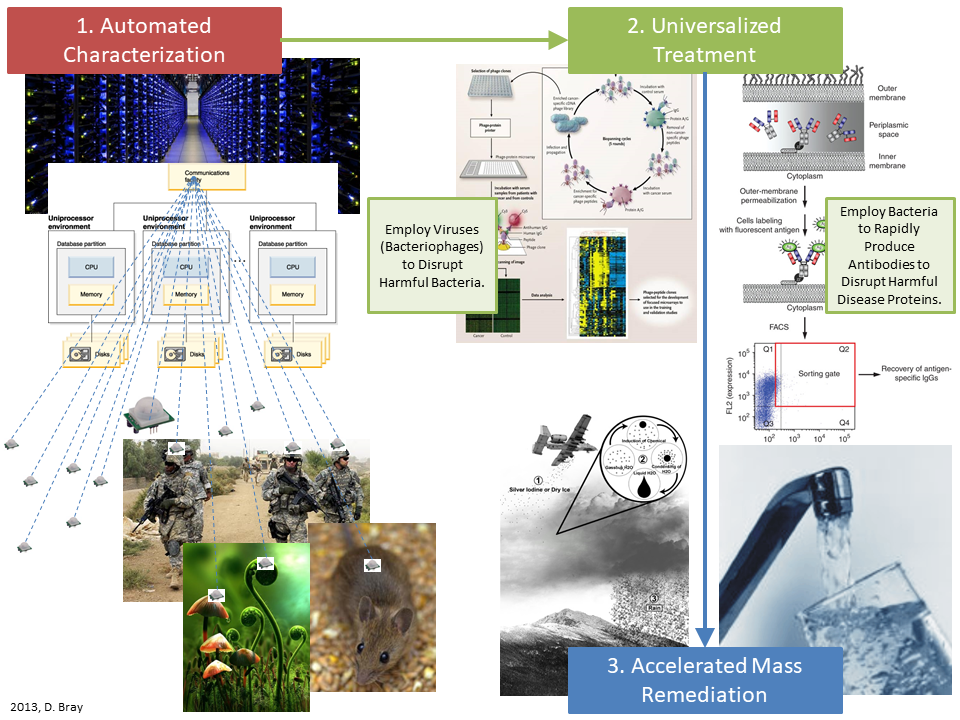

- Automate detection, by embedding electronic sensors into living organisms and developing algorithms that take humans “out of loop” with characterizing a biothreat agent

- Universalize treatment methods, by employing automated methods to massively select bacteriophages vs. bacteria or antibody-producing E. Coli vs. viruses

- Accelerate mass remediation, either via rain or the drinking water supply with chemicals to time-limit the therapy

Which, if these three steps are completed, would produce a globally distributed artificial “immune system”. The chart below, from the 2013 proposal, details what an immune system for the planet would do.

Other creative solutions that the next decade may need

In parallel to the pitches to DARPA in 2013 and 2016 were additional ideas that now, in the era of COVID-19, might be worth re-examining for the future ahead:

1. Herd Monitoring for the Internet – One such idea was whether the growing number of “Internet of Things” (IoT) and other devices online would exponentially challenge our already strained approaches to cybersecurity in terms of the sheer volume of devices online. The solution in 2016 was whether a “public health model” focusing more on monitoring what is abnormal behaviors for IoT devices, without revealing identities or specific actions tied to an individual, to protect privacy – would be superior at rapidly detect, contain, and mitigating threats.

The purpose behind the timing was to engage in such a public health approach to the IoT before mass exploits got really bad for societies around the world. Even in 2016 it was clear that IoT devices, with security models based on industrial controls, might have even worse security than Internet-based, TCP/IP endeavors thus creating a compelling urgency to do this. Moreover, with an eye to the future, the intersection of a more automated, public health approach to the “herd immunity” of IoT devices might pave the way for necessary future technologies and approaches to do the same in an era in which precision medicine, and thus the risk of precision poison, becomes available.

2. Your Own Digital Privacy Agent – A second such idea pitched both in 2013, and again in 2016, was whether technological steps could be done to empower consumers to decide when, where, and in what context their data should be shared with data requestors. By developing an open source agent or mobile app, consumers could choose to use it to be their trusted online broker when interfacing with other websites, mobile apps, or online services requesting their data.

The issue at the time was individuals are no longer in control of their privacy. End User License Agreements (EULAs) associated with apps and programs usually are too long for most people to read and parse. The concern in 2013 and 2016 was that trust in democratic institutions would wane if open societies did not come up to a solution the empowered individuals to make choices with regards to their personal data. The Internet of Things would only complicate this as would precision medicine at the volumes of data associated with that activity too.

3. Mechanism to Privatize and Mask DNA – A third and final such idea was to pursue mechanisms to privatize DNA, recognizing that in the very near future individuals high need additional safeguards to mask and keep secret their DNA. This stemmed in part from a projection of advances in precision medicine and biometrics that ultimately would mean a future where anyone could collect and sequence another person’s DNA.

As a result, knowing a person’s DNA might reveal what they are at risk health-wise or allow the equivalent of biological misinformation to be spread by others, such as copies of someone’s DNA could be placed at crime scenes where they had not personally been present. Back in 2013 and 2016, the ability to design DNA from scratch to tailor retroviruses was still maturing, yet new biological techniques have accelerated this capability. It will only be a matter of time before tailored retroviruses can be made, or even just the publishing of a famous person’s DNA to the Internet may reveal things they may not want known publicly about their health.

A call to action

COVID-19 is a case of a low-probability, high consequence event, i.e., a pandemic, finally happened. The pandemic will transform how our world operates and have ripple effects both on the development of new technologies and new ways of operating as societies in the aftermath.

Our approaches for pathogen detection & antigen development are too slow. Using high-speed computers, biosensors, and the Internet, we can universalize and automate the process for pathogen detection and antigen development, such that we can automatically sense an abnormal pathogen and immediately start synthesizing in a computer’s memory techniques to mitigate it. Once an abnormal pathogen is detected, we can automate the antigen development (e.g., phages, e. coli that eat other e. coli, and more) to have a solution ready much faster for possible use than conventional means. We can build an auto-immune system for the planet.

Such an endeavor is possible given advances in machine-learning and computational power. Such a concerted effort is needed given the continuing risk of a future global pandemics. The question being: will world leaders make the choice to invest in the future by beginning the necessarily technological and geopolitical conversations needed to make this happen today?

The GeoTech Center champions positive paths forward that societies can pursue to ensure new technologies and data empower people, prosperity, and peace.