Inclusive growth needs financial inclusion. Can central bank digital currency help?

Financial inclusion is central to promoting inclusive growth and shared prosperity. However, the latest data from the 2017 wave of Findex dataset shows that 1.7 billion adults remain unbanked: they lack an account at a formal financial institution or through a mobile money provider. While the number of unbanked today has decreased by nearly 1 billion as compared to the 2.5 billion unbanked people in 2011, large disparities in financial inclusion still exist across countries, gender, income, education, and rural-urban lines. Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) have the potential to enhance financial inclusion rates and reduce these disparities. To see the potential of CBDCs in this front, it is important to understand the factors driving inequalities in financial inclusion.

Most unbanked people live in emerging and developing economies (EDEs), with half of those people living in just seven countries: China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Mexico. Nonetheless, account penetration rates — the share of people aged 15 or older who have an account at a formal financial institution or mobile money services — have increased substantially in EDEs, causing a decline of around 800 million in the unbanked population of the world between 2011 and 2017. Specifically, the median account penetration rates among EDEs increased from 24 to 45 percent between 2011 and 2017 (Figure 1).

Women still represent a larger share of the unbanked as compared to men, composing 56 percent of all unbanked adults. While the gender gap in account penetration rates has remained small and constant in high income economies (HIEs), it has increased among EDEs. The median gender gap in account penetration rates in EDEs went up from 5 to 10 percentage points between 2011 and 2017 (Figure 2), highlighting the need for targeted efforts and policies to increase account ownership among females in EDEs.

More than half of the world’s unbanked are from the poorest 40 percent of households. While the median gap in account penetration rates between the rich and the poor declined in HIEs, it remained roughly the same in EDEs between 2011 and 2017 (Figure 3). To reduce inequality in financial inclusion across income lines, financial inclusion policies in EDEs should focus on increasing account ownership among poorer individuals in each country.

Low educational attainment is correlated with being unbanked. Over 60 percent of unbanked adults have only a primary education, or less. Moreover, the gap between the less educated and the more educated remained largely constant between 2011 and 2017 for both HIEs and EDEs, indicating the need for including less educated adults in the formal financial systems. This is especially true in EDEs, where the median gap in account penetration rates across educational lines remained above 20 percentage points between 2011 and 2017.

Finally, a larger share of the unbanked population resides in rural areas, especially in EDEs. While the available Findex data points to the narrowing of the urban-rural gap in financial inclusion across all regions of the world, in some countries, despite substantial improvement between 2011 and 2017, the gap remains to be significant. For example, while the rural account penetration rates in China increased from 58 percent to 77 percent between 2011 and 2017, still 200 million Chinese adults in the rural areas remain unbanked.

Education is the most important determining factor for financial inclusion, followed by gender, income, and age. By applying Probit probability regression models to individual level micro data from the 2017 round of Findex database, similar conclusions and a more complete picture are achieved (Table 1). Being female reduces the probability of having an account in all regions, but the results are statistically more significant for developing countries of LAC, MENA, SA, and SSA regions. The estimated regression coefficient for female variable is largest in the MENA region, followed by the SA region, referring to the larger inequalities in financial inclusion across gender lines in these regions. Education and income level have a positive and statistically significant correlation with probability of account ownership in all regions. Being older is also positively correlated with a higher probability of account ownership; however, the results are not statistically significant across all regions and the impact is considerably weaker when compared to education, income level, and gender

The size and level of significance of the regression coefficients in the above models indicate that education is the strongest determinant in probability of account ownership, followed by gender, income level, and age. In addition to increasing economic wellbeing and prosperity, greater educational attainment across a population would increase financial inclusion — defined here as account ownership. Next, to increase financial inclusion, policies must target the female population, as gender is the second most important factor influencing rates of account ownership. Finally, policymakers should pay attention to households in lower income quantiles and younger adults, as these groups are less likely to have an account when compared to richer and older individuals.

The introduction of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) could help increase financial inclusion. Many positive developments in financial inclusion over the past decade can be attributed to the role of technology, especially mobile financial services. Mobile banking makes it easier to provide financial services — mainly mobile payments — in areas with minimal or no physical banking infrastructure. Central bank digital currency (CBDC) is the most recent technological innovation with the potential to increase financial inclusion by reducing disparities across the dimensions highlighted above.

There are several challenges facing the unbanked population that could be ameliorated with the introduction of CBDCs. First, most banks and formal financial institutions have minimum balance requirements for having a bank account, making it hard and costly for the poor to have a bank account. At the same time, having a digital form of payment — such as credit card — is dependent on having a credit history. These services often come with annual fees, making digital forms of payment unattainable for many people in lower income deciles, especially those with poor or no credit history. Finally, with the recent coronavirus government stimulus serving as an example, in times of economic crises, government stimulus often has a hard time reaching the most vulnerable families — specifically the unbanked — in a timely and effective manner. That challenge lead to delays, lost mailed payments, and other complications for millions of unbanked American families. FDIC data suggest that as of 2020, 5.4 percent of American families — over 7.1 million households — were unbanked. Even in HIEs, challenges facing the unbanked are widespread.

With the introduction of CBDCs, everyone in a given central bank jurisdiction could potentially have a free and non-interest-bearing account with the central bank linked to a secure app on their cellphones or other devices. In the United States, this would increase account ownership and enhance access to savings and digital forms of payments as 97 and 85 percent of the US adults own a cellphone or smartphone, respectively. The same is true in many other economies around the world as cell phone penetration rates are nearly universal, with 80 to 90 percent of adults around the world having access to mobile phones or smartphones.

However, it is important to note that the potential benefits of issuing a CBDC could differ from one country to another. Considering the near-universal account ownership in formal financial institutions in HIEs, CBDCs are mainly seen as increasing the efficiency and speed of payments in these economies. They would also bridge the digital gap in payment systems by enhancing access to digital forms of payments across the entire population with access to smart devices. This impact is especially significant among individuals who cannot acquire credit or debit cards through their financial institutions for various reasons such as adverse credit history.

In addition to the above benefits, in EDEs, CBDCs could also increase financial inclusion across the entire population by reducing gaps in financial inclusion across education, gender, income, and age lines. In a CBDC jurisdiction, adults would be eligible for a direct account with central banks, removing the barriers and discrimination that are usually present when interfacing with formal financial institutions. This does not mean that financial institutions have no role to play in a CBDC environment. In fact, most countries that are exploring the idea of a CBDC, have sided with a two-tier system design where the CBDC is a direct liability of the central bank but real-time payments are processed through financial intermediaries.1 For more on this and other possible CBDC structure designs, please see https://www.bis.org/publ/work948.pdf World Bank’s Findex dataset identifies the main reasons for being unbanked according to respondents as: insufficient money, expensive accounts, distance from financial institutions, lack of necessary documentation, and lack of trust. CBDCs, by design, have the potential to reduce or remove these barriers and increase financial inclusion, especially among women, poorer individuals, and those with less education residing in EDEs.

CBDC is not the only player in the realm of mobile payments and e-money that could promote financial inclusion. M-PESA, WeChat Pay, Alipay, Zelle, various Stablecoins and many other platforms make mobile payment and digital forms of money possible, and have already contributed to financial inclusion around the globe for nearly a decade. From a strictly payment point of view and consumer’s perspective, CBDCs are simply another mobile, digital form of payment alongside many pre-existing ones. However, when processing government-citizenry monetary transactions such stimulus checks, unemployment benefits, and even paying taxes, CBDCs could make these transactions much more efficient.

Moreover, private mobile payment systems operate based on a claim framework, where transactions are not settled immediately and require a complex banking and clearing infrastructure to operate. CBDC or cash payments operate based on an object-based system, where the transaction is settled immediately given that both participants validate the payment. Finally, like cash, CBDCs are government-issued fiat currencies and are backed by issuing governments. Given the ability of CBDCs to cater to different preferences of the users and the improved efficiency of CBDCs in government-citizenry financial transactions, CBDCs could be a welcomed addition to the current mix in digital payment system infrastructure.

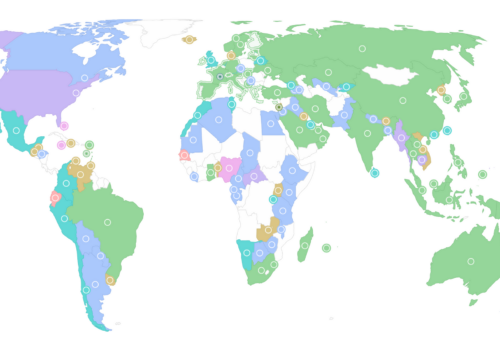

According to the Atlantic Council’s CBDC Tracker , 81 countries around the world — representing over 90 percent of the global economy — are experimenting with a CBDC, pointing to its immense potential. To ensure CBDCs are interoperable across borders with strong privacy and security standards in place, the US Federal Reserve should help lead the global standard setting discussions on CBDCs alongside other central banks, international fora like the OECD, and institutions including the Bank of International Settlements (BIS). At the same time, it is important for the financial inclusion community to pay close attention to the technical and regulatory developments on this front and keep alive the discussion on the financial inclusion aspects of CBDCs.

Related content

At the intersection of economics, finance, and foreign policy, the GeoEconomics Center is a translation hub with the goal of helping shape a better global economic future.