As Iran enters a new century, many old challenges remain

For Iranians, the upcoming spring solstice marks not just a new year, Nowruz, but also the beginning of a new century on their calendar—the year 1400. Despite significant advances in education, modernization, territorial cohesiveness, and purported regional influence, many of Iran’s old trials and tribulations remain. These include dysfunctional politics and gridlock and economic insecurity and inequality for a sizeable share of its eighty-three million population, as well as contentious foreign relations.

The years leading up to 1300 (1920-1921) were transformational worldwide. Beyond the destruction and millions of deaths it caused, World War I led to the disintegration of several empires including Iran’s neighbors—the Ottoman Empire and Czarist Russia. Despite its declaration of neutrality, Iran suffered invasions from the Ottomans, Russians, and British. Combined with a weak central government, this led to a widespread breakdown of internal order and security, as well as at least eight separatist movements. Additionally, a famine and the Spanish flu pandemic ravaged the already sparsely populated country and stretched its meager economy and services.

Political inertia

The Constitutional Revolution of 1906-1911 shifted the balance of power away from the Qajar monarchy to a parliament, whose members were elected for two-year terms from among the elite. However, as Ali Dashti, a deputy parliamentarian remarked at the time: “The majority of the present deputies are not versed in politics. They are mostly merchants and landowners who are not knowledgeable of political matters. It is therefore up to the government to have a policy and to have already decided the path it is to take.”

But the role of the government was unclear. As historian Fakhreddin Azimi explains, the Iranian Constitution “had not adequately clarified the position of the executive within the body politics. The executive was, thus, provided with few, if any, effective mechanisms for the assertion of its authority in the face of the legislature.” According to Article 46 of the Constitution, the King appointed and dismissed ministers, hence it would seem that the government was accountable to the crown. And young Ahmad Shah Qajar, who ascended the throne at the age of eighteen in 1914, changed no less than fourteen governments during his ten-year reign. As prime ministers were also answerable to the majlis, it, too, flexed its muscles and dismissed another seven governments.

As a result, as Azimi writes, “a substantial part of a minister’s time and energy was spent on cultivating his own personal and sectional links, returning favors, providing his clients with a feeling of sharing the spoils of office, and establishing a holdover the positions of his ministry by appointing personal friends and clients.” While the constitutional movement, which has been amply idealized, transformed Iranian politics, the experimentation with the people’s voice in state affairs did not produce the kind of stability, consistency, or decisiveness that the country required in the turbulent decade of 1911-21. Nor was it inclusive, as it disregarded women and minorities as citizens. Further to the dysfunction caused by personal vested interest and democratic infancy, an exceptionally inexperienced and disinterested Ahmad Shah was a recipe for Iran’s decline at a time of major global transitions.

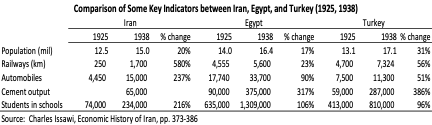

The country’s underdevelopment has been blamed mainly on foreign interference. Like many countries in the 19th century, Iran attracted concession hunters looking for lucrative opportunities. Some scholars believe that the concessions had a negative impact on Iran because they led to foreign economic exploitation. While concessions were mainly monopolies, which can be disadvantageous in the long run for competition and efficiency, there is strong evidence that foreign direct investment, particularly long-term risk capital combined with updated technology and knowhow, is a necessity for progress and growth. Despite Iranians’ widespread belief that foreigners dominated the economy, by the 1920s, foreign investment in Iran only amounted to around $150 million; it exceeded $1 billion each in Egypt and Turkey. Even in trade, Iran lagged. For instance, between 1911-1921, Iran’s per capita foreign trade—exports and imports—averaged $10 compared to Turkey’s $15 and Egypt’s $24. Added together, the foreign economic impact on Iran was in fact far less meaningful than its peers.

Several factors played a role. Iran was in relative geographic isolation because of its rugged topography, lack of navigable rivers, and dearth of modern transportation facilities. This made commerce between its relatively more productive northern provinces and the Persian Gulf more costly. Even with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Iran lay off the world’s commercial navigation grid. Above all, the political and economic developments of the late nineteenth century, followed by the impact of war, drought, famine, and the Spanish flu, had left Iran exhausted and impoverished when it entered its new century.

The Great Game

In his book The English Job (Kar-e Inglis), former British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw explains that “Iran is a proud country and intensely nationalistic.” It was never a colony, even in an era when European powers claimed territories all over. Therefore, understanding Iranians’ strong nationalistic and long-lasting anti-imperialistic sentiments require some explaining, especially when comparing these against the attitudes of nations that were colonized and later fought brutal wars for independence, but have since gotten over their grievances.

Iranians have long believed that their country was a rich land that Western powers coveted and, thus, resorted to conspiracy and machinations to exploit its resources. European countries were present in Iran since the 16th century Safavid period, but, from the 19th century onwards, Russia and Britain stood out. Russia was dominant in the richer northern provinces as a buffer to its oil-rich Caucasus regions, while Britain used Iran to shield India. British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury declared in 1889: “’Were it not for our possessing India, we should trouble ourselves but little about Persia.”

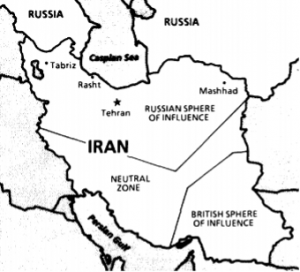

Source: Anglo-Russian Entente 1907

By the start of the twentieth century, the Anglo-Russian rivalry over Iran and large parts of Central Asia—known as the Great Game—was at its height. To defend itself, Iran played one side against the other. It became an exhausting tactic that ultimately distorted and corrupted internal politics. Tehran had little to no power to even select its own ministers without the approval of the British and Russian consulates. For instance, American financial advisor Morgan Shuster, who had been hired by the Iranian government, had to be dismissed under British and Russian pressure. His book, The Strangling of Persia, has become a classic testament to this debilitating dynamic.

The rise of Imperial Germany at the turn of the 20th century led Britain and Russia to paper over their rivalry in Asia and focus on the German threat in Europe. Within the broader Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907, the two powers divvied up Iran into zones of influence. Russia chose the productive north and Britain selected the economically marginal southeast that bordered India. Even though explorations under the 1901 D’Arcy oil concession were already under way in southwest Iran, this very region was left in the neutral zone, underscoring that Britain’s prevailing priority was ringfencing British India. Since the Entente was done behind Iran’s back, it has left scars that time has not been able to heal, particularly vis-à-vis the United Kingdom (UK).

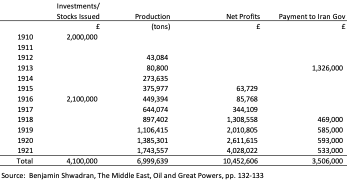

The decision of the British navy to switch from coal to oil and the subsequent finding of the latter in 1908 under the William Knox D’Arcy Concession, increased Iran’s importance for Britain. In 1914, the British Government decided to invest £2 million of taxpayer funds (estimated at £230 billion in 2020 prices), thus, doubling the capital of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC), which had been established in 1909. This injection of funds turned APOC into Britain’s single largest overseas investment and the oil royalties became Iran’s main economic lifeline, as shown below (Table 2).

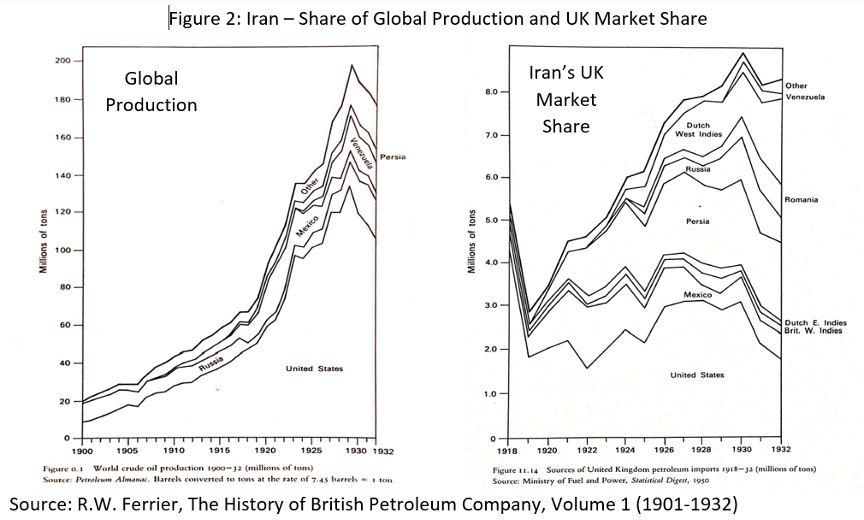

It would’ve been naïve to think that Britain would make such a huge investment without scaling up its influence to safeguard it. Consequently, Iran eventually became an important producer and a source of supply for Britain. Nevertheless, contrary to Iranians’ wide-held belief that Iranian oil was indispensable for the UK and the world, Iran’s share was small compared to some other producers and was not dominant in the UK over the next decades despite seeing growth (see Figure 2).

With the collapse of Czarist Russia, the Bolsheviks canceled all previous agreements, including the Anglo-Russian Entente, and offered Iran a Friendship Treaty instead, which was finalized in 1921. The post-war void of Russia tempted Britain to try its hand at total domination of Iran. In 1919, an agreement was negotiated that would have effectively rendered Iran a protectorate. Opposition to this agreement was fierce; it failed in the Majlis and backfired. Together, with the experience of the Anglo-Russian 1907 Entente, it further clouded the already contentious relationship with Britain and distorted Iran’s internal dynamics.

Rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi

It was under these circumstances that an officer of the Cossack Brigades by the name of Reza Khan—born into poverty and raised as an orphan—and some anglophile intellectuals marched on Tehran on February 22, 1921. They changed the government in a nearly bloodless coup under the then-ruling Ahmad Shah. Making himself the minister of war, Reza Khan established law and order over the next two years and subjugated the separatists and tribes. In 1923, he became prime minister and abolished the Qajar Dynasty (1789-1925) in 1925. He wanted to turn Iran into a republic modeled after Mustafa Kemal Ataturk’s Turkey. Fearing a fate similar to the Turkish clergy, Iranian clerics beseeched him to retain the monarchy and ascend the throne himself. The Iranian majlis voted 80-4 in favor of him as the new king.

Reza Shah embarked on a massive modernization of Iranian industry, institutions, and society. By getting things done and making plans happen that had long been on the drawing board, such as railroads and the modern judiciary, he is credited with laying the foundation for modern Iran. Toward the latter part of his reign, Reza Shah is criticized for becoming increasingly authoritarian and choking off Iran’s nascent democratic process by turning the Majlis into a rubber-stamp body and eliminating opponents.

In 1941, he was forced to abdicate by Britain when the Allied Forces invaded Iran to secure it as a corridor for aid to Russia against Nazi Germany. He was replaced by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who continued the modernization drive until 1979. During his time, Iran progressed economically and socially—women and minorities were no longer second class citizens—though “democracy” took a back seat again.

Persistent challenges

Although Iran has changed dramatically in the meantime and experimented with different political systems (most notably the 1979 revolution that deposed the monarchy), it faces similar challenges to those it confronted in 1300. Under the post-revolutionary constitution, the powers of the elected bodies of the president (i.e. executive/government) and the legislature/majlis remain ill-defined and are overshadowed by unelected institutions. Therefore, vested interest, corruption, and opaqueness slow down decision-making and blur accountability of officials. Not surprisingly, polls consistently show that Iranians fault internal politics more than externally imposed economic sanctions for their daily problems. Reports from inside Iran also point to rising income inequality and growing poverty. Additionally, Iran has continued to be at odds with important foreign powers—especially the United States, which replaced Britain as the Middle East’s hegemon—over a host of issues, impacting Iran’s internal and external policies despite its claims to independence.

At the dawn of their new century, Iranians still aspire for an accountable and effective government, social inclusion and economic security, and a productive and respectful collaboration with foreign powers.

Nadereh Chamlou is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was formerly a senior advisor at the World Bank. Follow her @nchamlou.

Image: A student visiting the Museum of Historical Cars on a field trip looks at a carriage (R) used by Qajar dynasty King Nasser al-Din Shah and the coronation carriage of King Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, in Tehran March 10, 2011. The carriages were both built in Austria and are housed at the museum which opened in 2001 and has a collection of rare antique cars belonging to the former royal families of Iran and private collections. REUTERS/Caren Firouz