MENA’s post-COVID resilience depends on using the talent pool of women

Women in advanced economies worry that the COVID-19 pandemic may have set back the several decades of progress that they had made in the labor market. The lockdowns affected functions that did not lend themselves to teleworking. The worst-hit businesses were in the services, care, and hospitality sectors, which happen to be female-intensive. Therefore, the economic recession has been called a “she-cession,” which was the central theme of the 2020 Women’s Forum for the Economy and Society. Its key finding was that there will be no recovery without a “she-covery.”

MENA and women’s economic opportunities

In advanced economies, the pandemic may be leaving long-term scarring on women’s economic opportunities, despite their having enjoyed a somewhat more legal level playing field with men. In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), where gender-based inequalities are many and deep-rooted, the concern for women’s setbacks could be more serious.

Inequalities of any kind impede the ability of individuals to offer and optimize their capabilities and to fend for themselves and their families in difficult times. Sex and gender-based inequality is the most wide-spread discrimination cutting across race, ethnicity, age, and class. It prevails in one way or another in all societies, but nearly all MENA countries are ranked within the lowest third of the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap Index. Though female education has risen considerably and there is hardly any schooling gap between the younger generations of men and women, MENA’s average female labor force participation (FLFP) rate is 24.6 percent, half the global average of 47.7 percent.

Why policymakers should care about gender inequities

Leading economies have struggled to regain growth and have used every trick in the fiscal and monetary book to blunt the immediate adverse effects of the pandemic. Low and middle income countries cannot do the same and deploy high levels of stimulus packages because of their smaller tax base and the limited coverage of their social assistance programs. For these countries, the World Bank suggests focusing on longer-term mechanisms of promoting growth instead of solely boosting short-term demand.

More than any other region, MENA has experienced adverse events that thwarted its economic potential for decades, such as longstanding wars and conflicts, displacements and refugees, and political uncertainties. Recovering from the COVID-19 downturn will be a formidable challenge. For this reason, addressing the low FLFP is important because it could be a source of growth. In 2014, Teignier and Cuberes estimated that Egypt’s gross domestic product (GDP) could be 29 percent higher with the elimination of the economic gender gap; the United Arab Emirates’ (UAE) by 31 percent, Lebanon’s by 28 percent, and Iran’s by 32 percent. The authors found that even advanced economies could still benefit from reducing gender disparities. But MENA’s gains could be several times higher. As Christine Lagarde, president of the European Central Bank said, “to boost growth, hire more women.”

Increased women’s economic participation improves not just the rate but also the quality of growth. Cross-country studies show that gender-based discrimination reduces income inequality and expands industrial output and export diversification. This supports the theory that disparities cause misallocation of scarce resources, particularly the use of ideas and skills.

Identifying solutions

Some causes of MENA’s low FLFP can be found in social norms that feed into hiring bias. For instance, it is not uncommon to hear opinions that men should get preference due to the scarcity of jobs. There are also job postings that explicitly say women need not apply or rules that women be selected only when no male candidate can be found. Therefore, even in “normal” times, women face a dearth of opportunities and higher unemployment than men. Expecting disappointing outcomes, fewer women enter the labor market and more drop out.

Two areas are high priority for raising women’s economic participation rates: (a) removal of gender-based legal barriers and (b) development of a market-based care economy.

Legal hurdles

Earlier this year when US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away, she was celebrated for her life’s work of pioneering the removal of gender-based laws that resulted in a de jure and de facto discrimination against American women in the workforce, access to social protection, and educational and civic opportunities. The series of cases that she defended as a lawyer in front of the US Supreme Court were transformational for American women’s rights in the public and private spheres and for opening doors and cracking glass ceilings. But, despite these rulings, American women still face discrimination and bias.

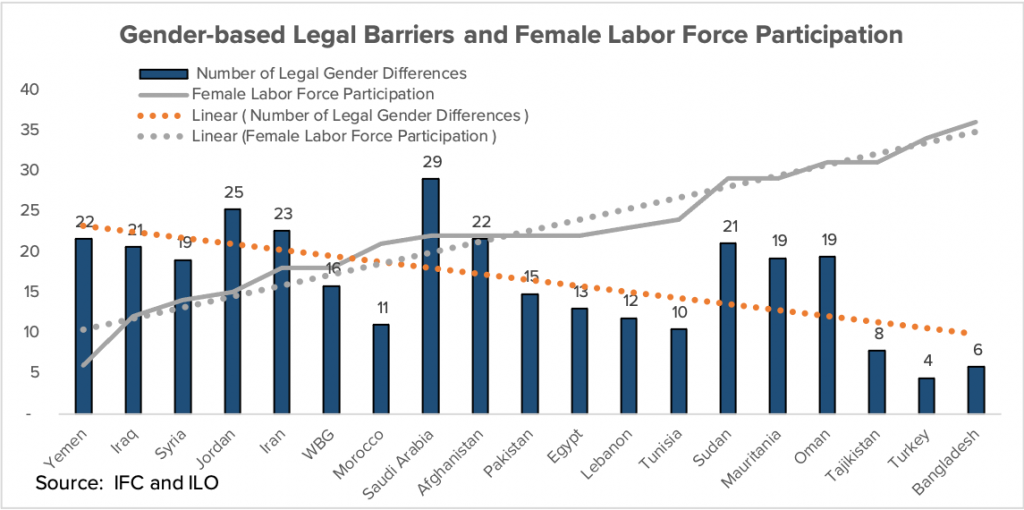

The legal barriers women face in MENA countries are by and large similar to those that American women faced some fifty years ago. They originate from the notion that women are not the primary breadwinners but secondary earners in the family and that the husband is considered the head of the household and the arbiter—even in matters that concern the woman’s decision vis-à-vis her own life and her interactions with the state. For instance, in most countries of the region, a wife still needs her husband’s permission to work, obtain a passport, or travel. The International Finance Corporation’s Women, Business, and Law report carries out a regular global survey of laws and regulations that impact women differently than men in the economic realm. Within this global survey, Muslim-majority countries have the highest numbers of gender-based barriers, albeit with large differences. The wide variance suggests that these legal hurdles may not be Sharia-based since many legislators have found ways to enact reforms. An International Monetary Fund (IMF) cross-country study found that more equal laws boost female labor force participation. The figure below demonstrates the trendlines of labor force participation versus legal barriers.

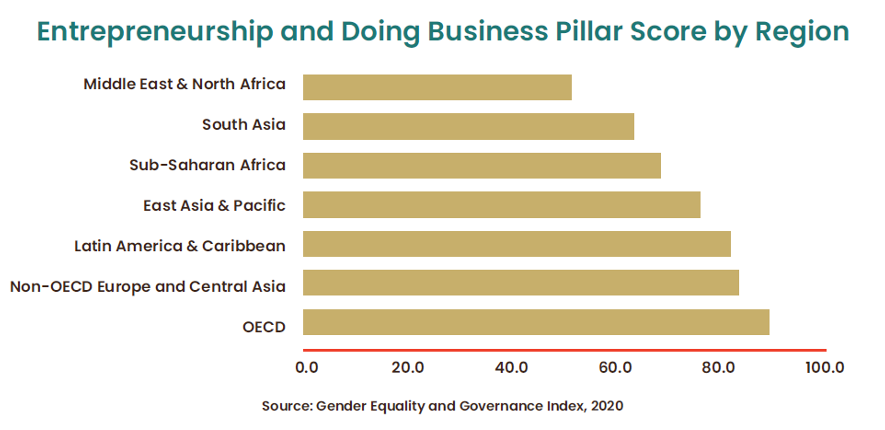

Equally important is a conducive entrepreneurship ecosystem for women. Due to a host of factors, most MENA countries have a less friendly business environment—even for men. The legal hurdles for women—in addition to a cumbersome investment climate—have been shown to result in considerable barriers to entry for women-led startups. Across the world, women report facing obstacles with respect to access to finance and support networks. Unsurprisingly, the 2020 Global Governance Forum report scored the MENA as the lowest among regions in this regard. Improving the general business climate alongside building a level playing field for women could be the engine of growth MENA economies need.

Then again, the MENA is also home to many paradoxes, which is cause for optimism. In 2008, a World Bank study found that one in every six to seven firms in the MENA’s formal sector was a woman-owned firm (WOF)—roughly 14 to 17 percent of the formal small and medium enterprises (SMEs) surveyed. This percentage is lower than in other developing regions where this rate is around 25 percent. Yet, counterintuitively, a larger share of WOFs in MENA were middle to large-sized rather than small scale—exactly the reverse pattern of other regions. They were as old, large, diversified, productive, and sophisticated as the male-owned firms.

How can the combination of fewer in number but larger in size WOFs in the region be explained? The existence of old and large WOFs indicates that women’s entrepreneurship is not a new phenomenon. In fact, one can easily find many cutting-edge women business leaders in each MENA country. The lower prevalence of smaller WOFs—despite the presence of successful businesswomen—in comparison to other regions suggests that there might be many more would-be-entrepreneurs who simply remain behind the high entry barriers. Those who make it are the strongest. Recently, many women entrepreneurs have found it easier to start abroad and re-enter their domestic markets as established business leaders, such as Tunisia’s Zohra Slim, co-founder of InstaDeep, a fast-growing London-based Artificial Intelligence solutions provider.

Addressing the myriad of problems facing the region requires the talents, hard work, goodwill, and ideas of every person, irrespective of gender or age. With rising women’s education levels, specifically in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, there is a growing trend of women-led tech ventures. Lowering gender-based barriers in combination with increasing visibility of this emerging segment to venture capitalists and angel investors could turn this niche into a growth industry for the region.

Care economy

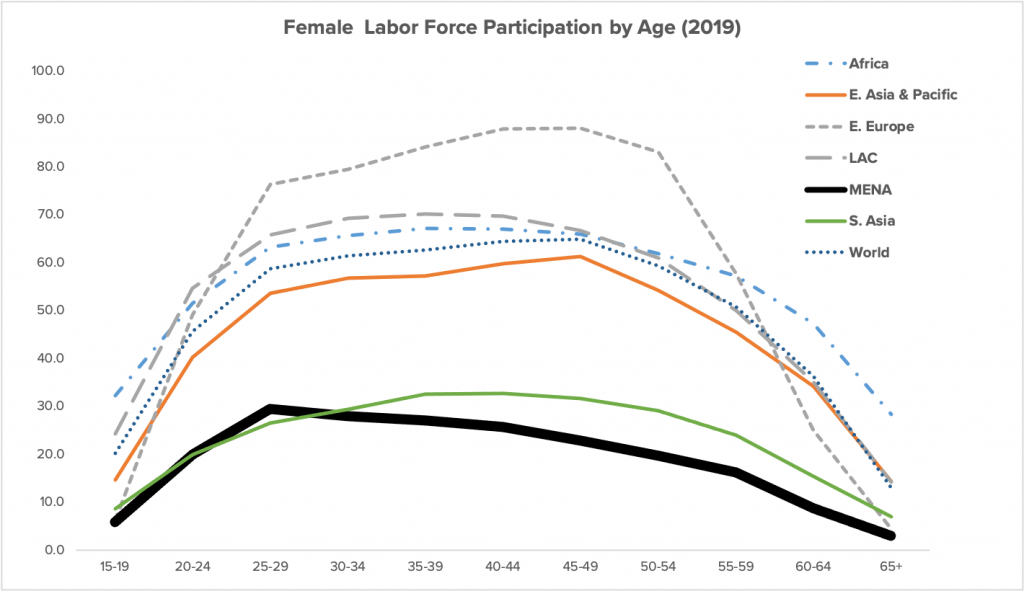

The cross-regional pattern of FLFP by age reveals that MENA women enter the labor force at a lower rate and drop out at disproportionately higher rates during their reproductive years. The pattern suggests that MENA women face additional pressures beyond the legal hurdles covered above. Women worldwide have families and take on a large share of the care functions, so what impedes the ability of MENA women beyond her peers in other regions?

A 2020 joint research effort by UNWomen and the Cairo-based Economic Research Forum (ERF) on the topic of the care economy finds that the MENA care market is vastly under-developed and imposes a disproportionately higher burden of unpaid work on women. The report finds that Arab women perform 4.7 times more unpaid care work than men—the highest female-to-male ratio anywhere in the world. It argues that “care is a public good that is fundamental to our societies and economies, with benefits that extend beyond those who receive it. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the wide gaps in care policies and services that require concerted efforts across the region. Over half (53 percent) of employed women in MENA work in care-related jobs, also the highest of any world region. Tapping into the potential of the paid care economy could, thus, be an important way to support women’s economic empowerment.”

Could post-COVID-induced telework adaptations boost FLFP in MENA? Yes, there could be more opportunities. But it must accompany the removal of legal barriers and the development of the care economy. “When women have to juggle their corporate day jobs along with a disproportionate share of family caregiving and housekeeping…the situation gets grim fast,” says Amy Bernstein of Harvard Business School’s Digital Initiative.

Some studies praise remote work for the flexibility it provides, but Herminia Ibarra, a leading global scholar of women’s empowerment at several renowned universities, thinks that “killing the office won’t close the gender gap.” In a recent Harvard Business Review article, Ibarra and her co-authors argue that COVID-19 has done the unimaginable in terms of removing the stigma of telework by forcing most jobs to be done remotely by men and women in leading companies. But, once the pandemic is behind us, she is doubtful that flexible work schedules can improve women’s empowerment and status in society.

Even in advanced countries, the jury is still out on remote work. A 2010 conference in The Netherlands, where flexible work schedules are a norm and where FLFP is close to 60 percent, found that, while women had jobs, men had careers. Therefore, despite their high participation rates, few Dutch women were in leadership and decision-making roles. Remote work will not change attitudes toward women’s status in society and could possibly serve as an excuse to avoid tough gender-intelligent reforms.

Conclusion

While every country has struggled to cope with the pandemic in its own way, there is concurrence on one issue: the world will not return to business as usual. The pandemic has exposed dysfunctions, vulnerabilities, and fault-lines that have been magnified by social and economic inequalities. It has created an urgency for profound changes—a kind of global “reboot—to tackle long overdue challenges that had been postponed because of complacency and lack of resolve.

The MENA region cannot afford to fall further behind. In order to build greater resilience, it must bring more women into the paid economy. This is why removing barriers to women’s economic empowerment must be front and center on the menu of actions that MENA countries should no longer postpone. As IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva put it: “What is good for women is ultimately good for addressing income inequality, economic growth, and resilience.”

Nadereh Chamlou is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was formerly a senior advisor to the chief economist at the World Bank’s MENA Department. Follow her @nchamlou.

The MENA Futures Lab at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East is shaping solutions to empower entrepreneurs, women, and youth and building coalitions of public and private partnerships to drive regional economic integration, prosperity, and job creation.

Image: Women work on a production line at the mobile phone factory in Assuit, Egypt September 30, 2018. Picture taken September 30, 2018. REUTERS/Mohamed Abd El Ghany