COVID-19: The latest shock to a battered Iranian system

How many shocks can a political system absorb and still remain in power?

That is a reasonable question to ask about the Islamic Republic of Iran, which has faced many daunting challenges during its 41-year tenure but especially in recent months.

The Trump administration’s decision to quit the 2015 Iran nuclear deal and seek to impose a total embargo on Iran’s oil exports cratered the Iranian economy, dashing hopes raised for significant growth and reintegration into international markets. The dire fiscal situation, in turn, pushed the government in November 2019 to raise gasoline prices abruptly. That triggered massive popular protests that the regime brutally crushed, at the cost of between several hundred and more than a thousand lives.

At the same time, Iran began retaliating against the US and its allies in the Middle East for the sanctions, which were re-imposed while Iran was still in full compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Starting June 2019, Iranian forces attacked oil tankers, brought down a US drone over the Persian Gulf and severely damaged Saudi Arabia’s main oil facility. Iran also began to exceed limits set in the JCPOA.

At the end of 2019, direct tensions with the US escalated to an unprecedented level after rocket attacks blamed on Iran-backed Iraqi militiamen killed an American contractor in the northern Iraqi city of Kirkuk. The US retaliated with strikes that killed 25 Iraqi militia members in Iraq and Syria. This led to protests at the US embassy in Baghdad and a US drone strike that killed Qasem Soleimani, the head of the elite Quds Force, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the head of the Iran-allied Kataib Hezbollah militia, near Baghdad airport on January 3.

Iran retaliated a week later, sending missiles against bases housing Americans in Iraq, causing no fatalities but brain injuries to more than 100 US military personnel. The tragic shoot-down the following night of a Ukrainian airliner—which Iran’s Revolutionary Guard mistook for incoming American fire—paused the conflict but did not end it. On March 12, rockets hit a base at Camp Taji north of Baghdad that houses thousands of American troops. Two Americans and a British soldier were killed. The US again blamed Kataib Hezbollah and retaliated with multiple strikes on its bases and weapons caches including near the Shia holy city of Karbala. The militia responded with more strikes of its own.

This new tit-for-tat cycle is taking place against a backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which has hit Iran particularly hard. Unwillingness to shut down travel to China, Iran’s economic lifeline where the virus originated, to quarantine Qom—where the first Iranian outbreak was reported—or to postpone February 21 parliamentary elections—led to a far worse situation than might otherwise have occurred. As of this writing, there have been more than 14,000 cases in Iran and more than 700 deaths, with the likelihood that the actual figures are much higher. In Qom, satellite photos show excavation of a massive new gravesite the length of two football fields to inter the rising toll from the epidemic.

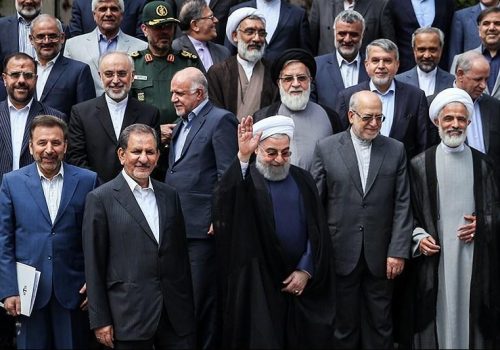

Infection has spread into the ranks of the Iranian government, killing two members of parliament and a member of the Expediency Council, a body that advises Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and settles disputes between government branches. Khamenei’s long-time adviser, Ali Akbar Velayati, as well as two vice presidents and the deputy health minister charged with managing the response to the epidemic have also been infected. The deputy minister was filmed at a press conference sweating profusely—a day before he was diagnosed with COVID-19.

The regime has responded by blaming others and also seeking emergency relief in the form of a $5 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund—a first for the Islamic Republic. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei tweeted that there was evidence that the virus was the result of biological warfare—a conspiracy theory also embraced by Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR), although he blamed it on China while Khamenei pointed to Iran’s adversaries, the US and Israel.

The popularity of the regime was already at rock bottom before the virus exploded—a function of the poor economy, government repression and lies and unrepresentative politics. Turnout in the parliamentary elections was the lowest ever reported in the Islamic Republic: barely 20 percent in Tehran and 40 percent nationwide.

But predictions about Iran’s political future are risky. So far, there are no signs of regime collapse despite all the challenges the country is facing and the fevered predictions of those in the West—and inside Iran—that regime change is imminent. If anything, the multiple crises have served to consolidate the power of the most hardline elements in the country and discredited those who sought a less confrontational stance toward the West.

Shaul Bakhash, a professor emeritus at George Mason University whose 1984 book, “The Reign of the Ayatollahs,” remains one of the best accounts of the 1978-79 revolution, says that a number of factors need to be present at the same time for the regime to be considered in serious jeopardy.

Among them, he said, are: “protests and demonstrations that are large, multi-urban (that is, taking place in more than one or two major cities), and that are sustained beyond a few days;” strikes that occur in major industries and the public sector that are also sustained; “a shutdown of the bazaar by the merchants and small business in sympathy with the anti-regime protests;” and, most importantly, defections within the security services.

So far, none of these are apparent. Indeed, the COVID-19 crisis makes public protests of any size even less likely for fear of spreading the disease. Most Iranians—like their counterparts worldwide—are now hunkering down at home.

This author has argued that regime change of a beneficial sort is more likely in an atmosphere of optimism and opening, not when Iran’s rulers feel they are fighting for survival against enemies—foreign, domestic and now biological. Unlike other authoritarian states where a single leader is pivotal, Iran has a large political and security elite and procedures for replacing Khamenei should he fall victim to COVID-19.

One consequence of all the crises is growing power for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and those who are close to them. If the theocratic system in place for four decades should fall, its replacement could well be a military dictatorship. This would not necessarily be an improvement on the status quo from the point of view of Iranians or of Iran’s adversaries.

Barbara Slavin is director of the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council. Follow her on Twitter: @BarbaraSlavin1.

Image: Iranian Health Minister Saeed Namaki (C) wearing a mask attended the meeting of the National Headquarters for Fighting Coronavirus convened in a session that was chaired by the President and attended by ministers and officials of relevant agencies (Reuters)