Mobilizing crowds to chant slogans at huge demonstrations is part of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s DNA. Such demonstrations, after all, propelled the 1979 revolution that overturned the Shah and still occur on a regular basis to commemorate events connected with the revolution.

In the aftermath of a series of stunning events over the past few weeks that have brought Iran and the United States to the brink of a major war, tens of thousands of Iranians have come to the streets again with a variety of motives and objectives.

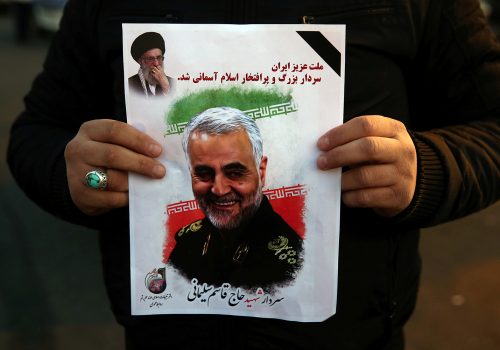

Some have demonstrated in support of Iranian nationalism after a US drone assassinated Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani. This outpouring in cities across Iran was followed in head-snapping fashion by large protests, primarily on Iranian university campuses, after Iran’s own government shot down a civilian Ukrainian airliner, killing all 176 on board. Officials appear to have mistaken the jet for a hostile US missile or plane retaliating for Iran’s own retaliation for the Soleimani killing—missile strikes on two bases in Iraq housing Americans that caused damage but no casualties.

Whenever protests break out in Iran, there is a tendency among some in the West to predict the end of the regime that has ruled that country for nearly forty-one years. But these demonstrations, while becoming more frequent, are unlikely to result in a new revolution. They could force the Iranian government to show greater accountability and respect for public opinion in the short term; they could also lead to a more hardline approach with even less tolerance for free expression.

In my trips to Iran over the past twenty-four years, I have frequently witnessed government-organized rallies. In 1996, protestors chanted “Death to Germany” after a German court indicted several top Iranian officials for ordering the assassination of Iranian Kurdish dissidents at a Berlin restaurant in 1992. Every November 4, regime loyalists gather outside the old US Embassy in downtown Tehran to commemorate the hostage taking of diplomats from 1979-81—still the original sin of the Islamic Republic in the eyes of many Americans.

February 11 is the day when large crowds mass each year at Tehran’s Freedom Square to mark the culmination of the protests that led to the fall of the Shah. Typically, the government buses in students and provides free lunch to bump up attendance. It will be interesting to see how many show up this year and whether there are counterdemonstrations that rival the official show.

In my experience, Iranians use many excuses to come out en masse on the streets— election campaigns, soccer wins, the culmination of the 2015 nuclear deal, and the annual ceremonies marking Ashura, the high point of the Shia religious calendar. The gatherings give young people a chance to meet in public in large numbers; the government usually lets them let off steam as a way to temporarily ease the repressive nature of various Islamic social restrictions.

Protests of a more serious nature have occurred since 1999, when students at Tehran University gathered in response to the closing of a popular reformist newspaper, Salam, by a clerical court frightened by the paper’s muckraking exposes. Thugs belonging to a government-backed group, Ansar-e Hezbollah, stormed a dormitory and threw several students off balconies, killing one and injuring others. In response, students in cities across Iran demonstrated for a week—at the time the largest such protests since 1979. President Mohammad Khatami, a reformist who had initially condemned the vigilante actions, sided with the authorities when he was warned by Revolutionary Guard commanders that the very system was at stake.

The next big explosion was in 2009 when Iran engineered the fraudulent re-election of Khatami’s successor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. An estimated three million people filled Freedom Square on July 25 of that year, demanding, “Where is my vote?” Sporadic protests continued for more than two years until the regime put Ahmadinejad’s two reformist rivals—Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi—under house arrest, where they continue to languish today.

More recently, working class Iranians have protested poor economic conditions, in late 2017 and early 2018, and again last November, meeting fierce repression that killed hundreds and incarcerated thousands. Visitors to Iran report a growing sense of hopelessness—in part because of the dashing of expectations following the unilateral US withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal, in part because of endemic government corruption and incompetence.

While the slogans chanted, including “Death to the dictator” and “Death to Khamenei” —referring to the cleric who is Iran’s supreme leader—may sound revolutionary, there are serious questions about how successful the protests can be. The regime has locked up many civil society leaders so that there is no one individual around whom protestors can rally—as they did for Khamenei’s predecessor, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, in 1979. Many who have protested have fled the country to swell the large diaspora in Europe and the United States.

So far, Iranian security personnel have remained loyal to the regime—again, unlike 1979 when the military and police defected in droves. As long as the repressive apparatus of the government is intact, it is likely that the latest protests will eventually fade as past ones have done, only to be followed by others.

The events surrounding the accidental shoot-down of the plane could motivate the government to show more transparency in the short term. However, with parliamentary and presidential elections coming up this year and next, hardline elements are likely to benefit both because the clerical councils that vet candidates will disqualify many reformists and because turnout is likely to be low, which favors more conservative contenders.

In this fraught atmosphere, the US government—instead of just tweeting blind support—should listen to the words of the protestors themselves. Students at Amir Kabir University in Tehran—one of the country’s elite academic institutions—published a manifesto this week in which they blamed both the Trump administration and their own government for Iran’s current predicament.

History has shown that external pressure rarely produces regime change unless it is combined with engagement that lessens regime paranoia. Thus the old Soviet Union collapsed both because it wasted resources on intervention in Afghanistan and neglected domestic development and because the Reagan administration embraced Mikhail Gorbachev as someone with whom it could negotiate arms control. Had the United States remained within the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, it would have given more space to the reformist/pragmatist camp in Iran and made life better for ordinary Iranians. It is not too late for the Trump administration to offer negotiations in a way that the Islamic Republic could accept.

Barbara Slavin directs the Future of Iran Initiative at the Atlantic Council and tweets @BarbaraSlavin1. She has visited Iran nine times.

Further reading:

Image: Protesters demonstrate in Tehran, Iran January 11, 2020 in this picture obtained from social media by Reuters via REUTERS