Fantasies of regime collapse in Iran come without a plan

Each time protests flare up in Iran, certain circles in Washington get excited at the prospect of regime change: the toppling of the clerical establishment in Tehran.

Exiles, some of whom have not stepped foot on Iranian soil for more than four decades, begin predicting the imminent demise of the Islamic Republic.

In January, as campus protests in several cities erupted over the authorities downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane, Reza Pahlavi, the former crown prince of the authoritarian monarchy toppled during 1979, insisted a new era was just around the corner.

“It’s just a matter of time for it to reach its final climax,” Pahlavi was quoted as saying at the Hudson Institute on January 15. “This is weeks or months preceding the ultimate collapse, not dissimilar to the last three months in 1978 before the revolution.”

A worthy question is why so many scholars and policymakers in the West believe scattered anti-government protests in the Middle East and North Africa—regardless of how justified, courageous or commendable—will lead to regime change. Few if any serious scholars think that protests against Vladimir Putin in Russia presage his downfall, or that the many protests in France will lead to another downfall of the Republic.

For now, the Iranian regime appears to have weathered the US economic onslaught from the “maximum pressure” policy and several outbreaks of public unrest, celebrating its forty-first anniversary on February 11.

In any case, many doubt the regime is so fragile as to collapse by mass demonstrations. Those of us who have lived in Iran and its surroundings over the last few decades have witnessed firsthand the depth and breadth of the regime’s hard and soft instruments of control. Based on our empirical observations, we, in the mainstream community of Iran scholars and journalists, are not at all convinced the regime is on the verge of collapse—a conclusion which generates a lot of friction between us and the Washington anti-regime machinery as well as the hopeful exiled Iranians longing to return home.

But street protests did lead to cataclysmic change in Iran twice in the last 70 years: once in 1953 and again in 1978. So it is worthwhile for scholars, journalists and Iran watchers to consider what would happen if the protests somehow did lead to the collapse of the regime in Tehran.

This author attempted to grapple with this issue for some months in 2018, speaking with Iran experts in the intelligence and diplomatic communities as well as Iran scholars. The results of that examination were grim.

In the months before the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, the State Department drew up the Future of Iraq Project, a detailed study of how to address issues in the country such as water, energy agriculture, public health, security, infrastructure, education, justice, and the media. The results of that detailed study were famously ignored during the occupation, as triumphant war planners in the George W. Bush White House and Pentagon essentially winged it, with disastrous results.

Even if the United States were to learn the lessons of that debacle, there is little evidence a similar such study is being undertaken now. A well-connected interlocutor told this author that as the maximum pressure campaign was getting underway in May 2018, he had learned from key officials that no such contingency planning exists.

Even if such a plan were in place, would President Donald Trump, Vice President Mike Pence or Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) even deign to take ownership of the regime collapse its policies inspired? How would Russia and China react, if the US were to deploy a stabilization force of 10,000 or 20,000 forces to guard oil facilities and sensitive sites?

The western track card on redoing Middle East regimes is not promising. Attempts at regime change in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya have generally resulted in ongoing failures that gave space for militant groups and insurgencies.

According to calculations made by this author, diehard supporters of the Iranian regime may number perhaps 15 percent of Iran’s population of 80 million. That’s at least 2.5 million families, and a potential pool of 500,000 adult males willing to fight and die to restore the system.

Another dilemma facing a post-regime Iran is who would take over in a transition period. Again, the recent histories of other countries in the region are dismal. Regime opponents in Iraq and Libya had a proven track record of working across ideological and political lines in their exile years. Still, their countries sank into infighting and sometimes unspeakable violence once their longtime rulers were toppled.

Iran’s opposition abroad is polarized, fractured and politically immature, less-focused on potentially governing the country than with scoring points against each other in social media wars. Despite apparent Trump administration support for opposition figures abroad, former US national security officials have told this author that they harbor deep suspicions about their goals and capabilities.

Regime change advocates abroad have already discounted reformists as a legitimate alternative to the hardliners in the regime, potentially sabotaging a Tunisia-like transition where members of the country’s elite gently shove out an unpopular leader while taking up the reins of power, along with local labor unions and civil society groups.

The regional and global aftermath of US-engineered regime collapse could also be cataclysmic for a number of reasons. It would impact oil prices, refugee flows from the Middle East and the balance of power in Eurasia. Long-oppressed ethnic minorities along Iran’s eastern and western borders could announce breakaway regions that could destabilize neighboring nations, including US allies such as Iraq, Pakistan or Azerbaijan.

But aside from the obvious, the Iranian regime today is far different than Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 2003 or Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi in 2011. A strata of Middle East Islamist populists make up the ranks of the pro-Iranian realm that in many ways transcend Iran’s geographic delineations. How would they react to regime collapse in Iran? How would the Shia clergy which influences hotspots from the Levant to the Hindu Kush?

Iranians like to describe themselves as more “civilized” and genteel than their neighbors in the region; exiles fantasize of establishing a peaceful, pluralistic system that might include monarchists, liberals, and perhaps even some elements of the reformists inside the country.

But hardline Iranian regime advocates loyal to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei have repeatedly shown they are willing to use violence to retain power and will almost certainly do so in the aftermath of any regime collapse.

The Iranian regime has many arrows in its quiver of security options ranging from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ (IRGC) fanatical citizen militias to battle-hardened fighters from Lebanon and Iraq that could easily prevent a gentle transition if it is ever ousted.

As several western officials told this author, the denizens of the former regime will have no choice but to fight. “They are not going to just melt away and change,” one said. “They’re going to stay and fight. They can’t go to Switzerland. They’ll take lethal risks that no one else in the mix will take.”

In pushing for regime collapse in Iran, US officials should at least be aware of what they’re courting. Even if their policy is successful, it could be more disastrous than what they’ve ever imagined.

Borzou Daragahi is an international correspondent for The Independent. He has covered the Middle East and North Africa since 2002. He is also a Nonresident Fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Security Initiative. Follow him on Twitter: @borzou.

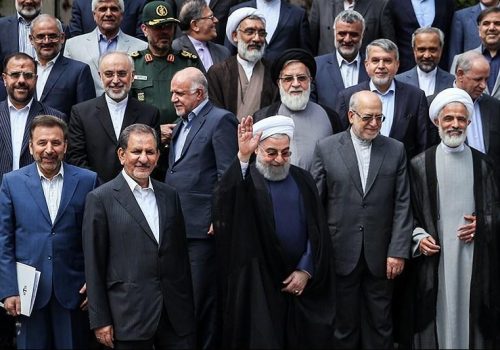

Image: Vice President Mike Pence and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo look on as President Donald Trump delivers a statement on Iran (Reuters)