Since the 1979 revolution, the United States has been waiting for the Islamic Republic to fail. Yet the regime has withstood an eight-year war with Iraq, decades of sanctions, and the 2009 massive internal uprising known as the Green Movement. It remained stable even as waves of democratizing “color revolutions” and uprisings swept through Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, east Asia, and the Middle East. Indeed, despite these challenges, the power of the regime seems to have grown, as Iranian proxies across the Middle East, from Lebanese Hezbollah to Yemen’s Houthi rebels, have disrupted foreign states and extended the influence of Iran-leaning Shia groups across the region.

Why has the regime been so stable? There is no single reason. Rather there are half a dozen reasons why the Islamic Republic has been so resilient in the face of extraordinary internal and external pressures.

First, revolutionary regimes that were forged in warfare are more durable than most other regimes. This is merely a fact of history. Revolutionary regimes that are tested by wars have to develop strong militaries and effective bureaucracies, and to temper or eliminate all internal divisions in order to survive. The result is a revolutionary leadership tempered by battle, usefully paranoid, and consisting of veterans who, no matter how divided, share a common bond of having sacrificed to defend the revolutionary regime, and will continue to do so.

Second, sanctions have provided excuses to the regime for poor economic performance. No doubt the Islamic Republic, like many semi-authoritarian regimes, has suffered from corruption and economic mismanagement. Well-connected elites have taken over much of the economy, while average citizens suffer from inflation, low productivity, and bouts of stagnant economic growth. Still, the presence of strong sanctions for most of the Islamic Republic’s existence has provided a convenient external scapegoat. However poor the regime’s policy, it is always possible to deflect blame to the “Great Satan,” the United States, that has been—in their eyes—bent on the Islamic Republic’s destruction. No matter that sanctions are supposedly crafted to mainly hurt the regime; ordinary Iranians are sharply impacted by the decline of the rial and hindrances to investment and imports. As the Associated Press recently noted: “one thing those in the beating heart of Iran’s capital city agree on: American sanctions hurt the average person, not those in charge.” Iranians might detest aspects of their regime; but they detest even more the pressure put on that regime by foreigners.

Third, a menacing girdle of wars in neighboring countries, spearheaded by US troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, have maintained fear and nationalism in Iran; both feelings increase support for the existing regime. These wars also justify continued military spending and a key political role for the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and underpin hawks in the Iranian government with respect to foreign affairs.

Fourth, although the ranks of revolutionary leaders might seem divided between “hardliners” in the IRGC and amongst clerics, versus “pragmatists and reformers” in the circle of Iranian presidents—such as Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammad Khatami, and Hassan Rouhani—these divisions are not as deep as they might seem. In fact, all of Iran’s leaders have either been clerics or had close ties to the clerical leadership. At the height of the 2009 Green Movement, the opposition presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, to whom the rebellious crowds looked to in order to oppose the fraudulent re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad—who was backed by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—could not bring themselves to denounce the Supreme Leader, or to break with the revolutionary regime. This lack of any effective elite leadership crippled the 2009 uprising. When there have been divisions among the revolutionary leadership, leaders always chose to settle their differences within the framework of the revolutionary regime, never to simply oppose it.

The notion that there are pro-Western “moderates” in the Iranian leadership who will oppose the authoritarian rule of the Supreme Leader or the anti-Sunni and anti-Western aggressive foreign policy of the IRGC is something of a myth. All of Iran’s leaders are committed to the revolutionary regime and to strengthening the Islamic Republic. Having that been said, the disputes are over tactics: will a pragmatic degree of cooperation with the international community—advocated by President Rouhani—strengthen their country more than an aggressive and confrontational regional strategy—advocated by the leadership of the IRGC?

The idea that pro-Western “moderates” are waiting in the wings, so that if enough sanctions or protests weaken the hardliners this will tip the balance toward regime change, is based on false premises. Even pragmatic Iranian leaders will not forget the US role in the region, from supporting the shah, to supplying Saddam Hussein’s Iraq when he was waging war with chemical weapons against Iranian soldiers, to shooting down a civilian Iranian airliner, and spurring disruptive wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya. The idea that more US pressure would somehow be welcomed and lead to a more pro-Western government is a dangerous illusion.

Fifth, the Islamic Republic may be religious-led and can be morally oppressive, but it has had mostly free elections that allowed Iranians to express their preferences regarding the regime. While electoral candidates are carefully vetted by the Guardian Council, it was still the case that many of the presidential elections led to surprise victors: this was true for Khatami in 1997, Ahmadinejad in 2005, and Rouhani in 2013. In each case, the outcome of the election was greeted as a shocking surprise. Whatever one says about elections in Iran, they cannot be wholly rigged in advance if hardly anyone could predict their outcome. The one exception was the 2009 presidential election, in which the obvious rigging of the outcome so angered the Iranian population that it produced the largest national uprising since the 1979 revolution. With that exception, the regime has allowed the population to vote on a relatively diverse range of candidates and allowed the population to express a desire for reform or change of direction within the framework of the Islamic Republic.

Finally, revolutions have a characteristic lifespan. If they withstand their initial testing through civil or international warfare, they gradually move to a more pragmatic phase, to create a more stable and balanced administration, over the next few decades. In Iran, this corresponded to the Rafsanjani and then Khatami presidencies. But this period is then often followed by a more populist, radical phase that reasserts the revolutionary character of the regime. This corresponded to the Lazaro Cardenas presidency in Mexico, the Proletarian Cultural Revolution in China, and the Stalinist collectivization campaign in the Soviet Union. In Iran, the Ahmadinejad presidency took on this role. But that “second radical phase” often has limited success, and a more “normal” national government follows. However, that government is still usually led by men and women who experienced the revolutions as youths, and grew up defending it. Thus, it is usually stable for another several decades. Hence the normal lifespan of a radical revolution—whether in France (1789 – 1871), Russia (1917 – 1991), China (1949 and counting), Cuba (1959 and counting) or Mexico (1910 – 2000)—is measured in seven to ten decades before a more pluralist, post-revolutionary government emerges.

The Islamic Republic will likely become a looser, less rigid, and more pragmatic or open at a future date. But if we look at other revolutionary regimes that survived a testing youth, that process typically takes two to three full generations. As the Islamic Republic was born only in 1979, it is likely to last at least until mid-century or longer.

Jack A. Goldstone is the Virginia E. and John T. Hazel Jr. professor of public policy at George Mason University and a global policy fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center. He is the author of Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World and Revolutions: A Very Short Introduction.

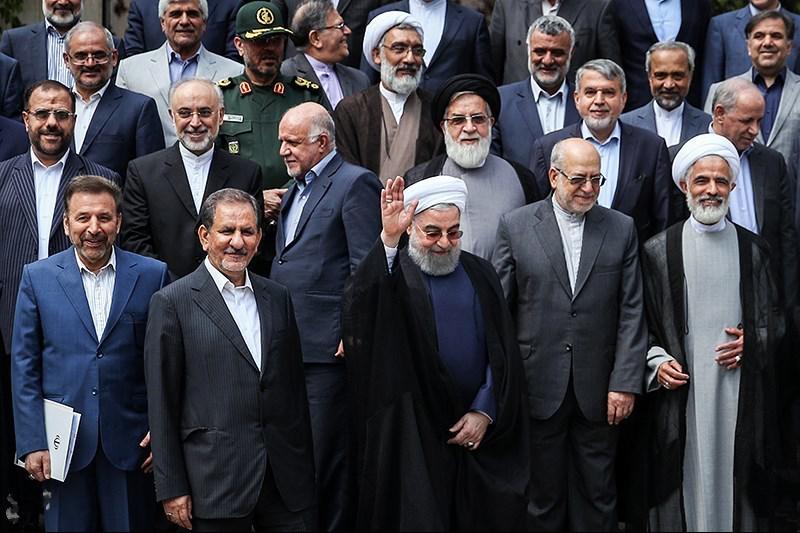

Image: Iranian President Hassan Rouhani's government during 2013 - 2017 (Wikimedia Commons)