I was once conscripted into the Iranian armed forces. Here’s why the IRGC designation is punishing conscripts.

I was a 19-year-old high school graduate when I was ordered to report at 4 am to the headquarters of the Law Enforcement Department of the Draft in downtown Tehran. I waited for two long hours until several officers arrived from the Artesh (regular military), Iranian Ground Forces, Air Force (IRIAF), Law Enforcement Forces (Prisons Branch), and Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Navy (IRGC-N). They were tasked with randomly picking conscripts. The officers began pointing at disheveled young men, commanding the frightened recruits to go stand in various lines associated with the military. Draftees were then given paperwork telling them to show up at one of Tehran’s bus terminals two days later to be sent to boot camp.

I would end up being picked by the IRIAF, but the process was arbitrary. After completing basic training outside of Semnan Air Defense Base, I received some mediocre training as a member of the military police and mostly did office work.

Like other Iranian men who seek to come to the United States, I was asked by an immigration officer in 2004 about my prior military service. The officer seemed relieved to hear that my twenty-one months of compulsory service was in the Artesh or regular armed forces.

In 2019, the US State Department designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist organization, an unprecedented action against the military of a foreign state. This effectively barred any Iranian who had served in the IRGC—conscript or otherwise—from entering the United States. Now, one of the final issues in the Iran nuclear negotiations in Vienna to revive the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) has been the Iranian demand that the IRGC be taken off the US list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs).

The legal provision can be found in Section 212 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 US Code § 1182. However, unlike members of al-Qaeda or the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)—whose members are presumably committed to the groups’ ideologies, aims, and terrorist methods—most members of the IRGC are conscripts and had no choice about which military branch they would join to fulfill their required military service.

Furthermore, most conscripts, especially those with no higher education, end up doing manual jobs, such as cleaning, cooking, or construction or, if they are lucky and have connections, driving for a senior officer. Most IRGC draftees end up doing similar jobs, too, including running personal errands for officers.

Depending on their field, those with higher education can end up with higher-status duties. Lawyers, for example, may work as the equivalent of a US military judge advocate general, investigating crimes committed by service members. A computer engineer would serve as a computer operator and so on. They, like less-educated conscripts, are often disciplined for minor infractions. In the case of the IRGC, a clean-shaven face could result in three days of extra service time, as I was told by a number of friends who were drafted by the IRGC.

Since the Iran-Iraq War ended in 1988, most Iranian conscripts have seen no combat, and their military service is often devoid of actual combat training. They are also often mistreated by officers. Like most draftees around the world, Iranians are eager return to civilian life as soon as their mandatory enlistment ends. However, unlike their government, which has hostile relations with the United States, many of these draftees yearn to pursue a better life in the US and fulfill their dreams.

Indeed, it can be argued that only a small minority of IRGC members, particularly those who served in the elite Quds Force—the Guard’s external arm—participate in acts that might be characterized as terrorism or support for terrorism in countries such as Iraq, Syria, Yemen, and Lebanon. The IRGC is made up of about 190,000 active personnel at any given time—the majority of whom were conscripted.

Iran has a compulsory military service requirement for all Iranian men when they reach the age of 19. The first compulsory military service bill was passed ninety-six years ago, during the reign of Reza Shah Pahlavi. The bill was later modified in the 1980s after Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran in 1980; it states that it’s the duty of “all Iranians” to defend Iran’s independence and territorial integrity. Any Iranian man who fails to provide documentation about the status of his military service cannot obtain a passport or conduct legal businesses.

The law, however, provides exemptions in certain circumstances. For example, those who are accepted to universities are exempted while at school but are required to sign up after they graduate. They must report at a specific date to the headquarters of the Law Enforcement Department of the draft—a unit of the Iranian police—which is in charge of paperwork and summoning draftees for service.

In addition, the law provides exemptions for those with severe medical conditions or the “bread winners” of the family. Nevertheless, most of these exemptions are only valid in peacetime and those carrying an exemption card are required to report for duty if there is wartime mobilization.

It’s unclear yet whether a US decision to lift the FTO designation of the IRGC will erase the stigma of having served in the organization as far as US immigration is concerned (separate financial sanctions on the IRGC will remain). Given the tens of thousands of Iranians whom the IRGC drafted over the years, it’s likely that many have relatives who are part of the large Iranian diaspora in the United States. Denying so many young men the chance to pursue their dreams for crimes they didn’t commit deprives the United States of their potential contribution and is at odds with the ideals on which the United States was founded. Indeed the Iranian diaspora community is one of the most successful ethnic minority groups in the US, with many celebrated scholars, scientists, and academics.

Allowing such people to travel to the United States can also be an effective tool to counter the propaganda of the Islamic Republic, which positions the US as the enemy of Iranians. After the bitter experience of the Donald Trump administration’s “Muslim ban,” subsequent withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, and “maximum pressure” campaign, easing restrictions on the immigration of innocent Iranians, who had no choice about serving in the IRGC, could be a collateral benefit of restoring the JCPOA.

Sina Azodi is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council and a visiting scholar at the George Washington University’s Institute for Middle East Studies. He is also a PhD Candidate in International Relations at University of South Florida. Follow him on Twitter @Azodiac83.

Further reading

Tue, Dec 8, 2020

A history of continuity in Iran’s long nuclear program

IranSource By Sina Azodi

Iran’s interest in developing a nuclear deterrent is often attributed to the Islamic Republic. However, in reality, this interest predates the 1979 revolution and reflects a deep-seated desire for national prestige and development, as well as a need to deter regional rivals.

Wed, Sep 1, 2021

An escalating Israel-Iran conflict could sink the JCPOA

IranSource By

Rising tensions between Israel and Iran have reached an alarming stage in recent weeks. What used to be a shadow war of covert operations, sabotage, and proxy conflict is turning into a more direct military confrontation between the long-time regional adversaries.

Wed, Mar 31, 2021

How Iranian Phantoms pulled off one of the most daring airstrikes in recent memory

IranSource By

On April 4, 1981, eight F-4 Phantom fighter bombers conducted a daring airstrike on three airbases deep inside Iraqi territory.

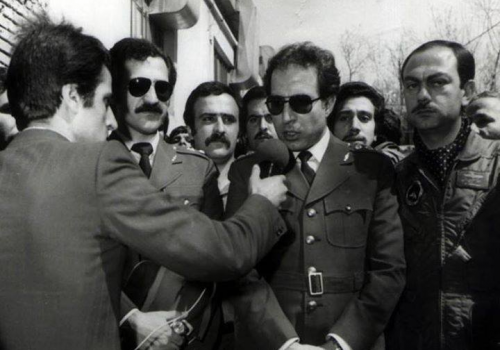

Image: Iranian army military personnel hold Iran flags while attending a funeral for the Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) unknown martyrs in downtown Tehran on January 6, 2022. Thousands of Iranians attend a funeral for 150 Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) unknown Martyrs that have found by the Iranian Martyrs investigation group in the war main field 34-years after a ceasefire between Iran and Iraq in 1988. (Photo by Morteza Nikoubazl/NurPhoto)