Iran joining the SCO isn’t surprising. But Beijing’s promotion of illiberal norms in Eurasia should get more attention.

The Islamic Republic of Iran’s ongoing quest for international legitimacy got a boost on July 4 when it finally became a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Council (SCO). Iran has long coveted this status, having first applied in 2008 after joining as an observer in 2005.

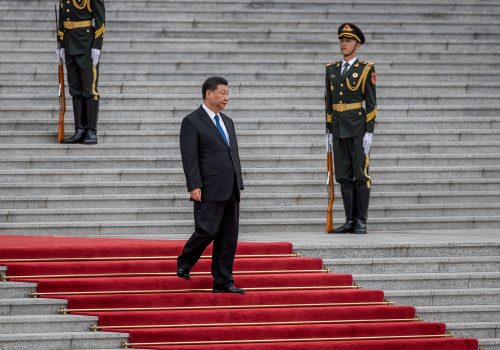

During the 2021 SCO summit in Dushanbe, Tajikistan, Chinese President Xi Jinping gave an opening speech in which he announced that the organization would “launch procedures to admit Iran as a member state.” Nearly two years later, this has come to pass. While it’s important not to overstate the geopolitical implications of the SCO itself, deeper coordination between Iran and other member states gives momentum to the China-centered illiberal order being promoted by Beijing.

The SCO started life as the Shanghai Five in 1996, consisting of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, and Tajikistan. Its effectiveness in dealing with territorial disputes that arose from the collapse of the Soviet Union convinced its members to develop and expand the organization, rebranding it as the SCO in 2001 and admitting Uzbekistan. Several countries have joined as observer states and dialogue partners, but no new full members were admitted until India and Pakistan joined in 2017.

Despite its early post-Cold War successes, there has always been a gap between the SCO’s size and its impact. It is often given weight with big numbers: its member states encompass 40 percent of the world’s population, 60 percent of Eurasia’s landmass, and 20 percent of global GDP. However, the organization doesn’t actually do much. Security cooperation has been the notable outcome, animated by a shared concern with the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism, and extremism. The SCO has institutionalized this through the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure and a Collective Security Treaty Organization. Nevertheless, efforts for deeper economic integration have been stalled for years, and the fact that its two most populous and wealthiest members—China and India—are bitter rivals makes political cooperation a challenge.

Still, for Iran, membership has its privileges. Beyond the status that comes with being part of a growing international organization, it also sends a message to the United States and European Union (EU) that “[Iran] can come out of isolation without revising the JCPOA.” Deeper coordination with China and Russia is another factor that cannot be overstated. Those two, along with Iran, are deeply dissatisfied with the norms of the Western-centered international order. In isolation, each of the three face limitations in projecting power and influence in the face of the US and its allies and partners. Together, however, they act as force multipliers. As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley recently said, “[T]hose three countries working together are going to be problematic for many years to come.”

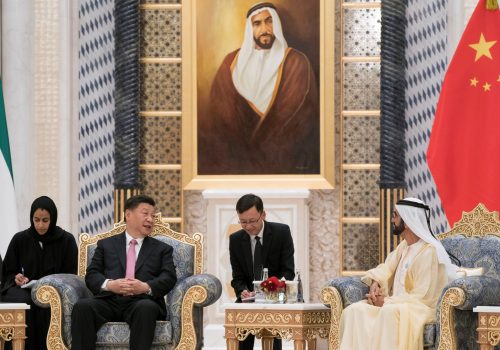

As a larger organization, however, the SCO is less than the sum of its parts. The admission of India as a full member dilutes Chinese and Russian influence. Furthermore, with American partners and allies—including Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—joining as dialogue partners, it is less likely that the SCO will represent an anti-Western bloc. Differences between member states and weak institutional bureaucracy also contribute to an organization that lacks the capacity to act as more than a talking shop.

At the same time, the evolving shape of the SCO as it takes on new members may present normative challenges. An important insight from the late political scientist John Ruggie was that the international institutions established after World War II were shaped by an “embedded liberalism” that animated interactions within them. Free markets, international institutions, cooperative security, democracy, collective problem-solving, shared sovereignty, and the rule of law are all features of these institutions and are promoted through participation. This embedded liberalism has continued to privilege those countries that set the rules of those institutions and the broader order they support, and this remains a source of dissatisfaction for those whose political values are at odds with them.

The SCO represents something different: a large international organization based on embedded illiberalism. The organizing principles of Western-developed institutions often diverge from the preferences of governments in the SCO. Even India, the world’s largest democracy and a key US partner, has taken a decidedly illiberal turn under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The SCO could be a key platform for institutionalizing authoritarian cooperation and resilience.

China has steadily been developing its homegrown alternatives to liberal norms, working to make “a world safe for autocracy,” in the pithy phrase of political scientist Jessica Chen Weiss. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has received much of the world’s attention, but, in recent years, China has been buttressing it with new offerings that will also appeal to authoritarian governments.

Xi rolled out the Global Development Initiative (GDI) in a 2021 speech at the United Nations General Assembly, calling for “global development toward a new stage of balanced, coordinated and inclusive growth” rather than that promoted by Western liberal values. In April 2022, Xi delivered another speech with another project, the Global Security Initiative (GSI), framed as another public good from Beijing that represents a normative alternative from unipolarity under the US in the post-Cold War era. This past March, the Global Civilization Initiative was introduced, calling for an approach to global politics that rejects universalist principles while asserting that countries must “refrain from imposing their own values or model on others.”

All three initiatives are vague and aspirational at this point—much like the BRI was for nearly the first two years of its existence. The release of the BRI white paper in March 2015 gave direction to what was initially dismissed as “a new slogan on stuff they’ve wanted to do for a long time.” Expect the same for these three. The ambiguity is the appeal at this point; by speaking in general terms about concerns shared by many countries of the Global South, Beijing is building momentum for “an increasingly comprehensive vision of a new global governance system” with China at the center.

For Iran, SCO membership is cementing its alignment with authoritarian states. This is entirely on-brand and not at all surprising. However, as the SCO continues to expand across Eurasia, the organization’s ability to promote Beijing’s preferred illiberal norms makes it a challenge that deserves more attention.

Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and host of the China-MENA Podcast. He is also an associate professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

Further reading

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Wed, Apr 5, 2023

China is getting comfortable with the Gulf Cooperation Council. The West must pragmatically adapt to its growing regional influence.

MENASource By Joseph Webster, Joze Pelayo

The US and its allies and partners must pragmatically adapt to China’s growing regional influence by providing credible alternatives to Beijing.

Thu, Jul 14, 2022

Biden’s Middle East trip focuses on the region. But China is the elephant in the room.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

US President Joe Biden’s visit to the Middle East on 13-16 July won’t directly focus on China. However, the rising power will be the elephant in the room at the Saudi summit in Jeddah.

Image: Participants of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit attend an extended-format meeting of heads of SCO member states in Samarkand, Uzbekistan September 16, 2022. Sputnik/Sergey Bobylev/Pool via REUTERS