Iran’s reformists don’t have a strategy yet—let alone a candidate

In an op-ed recently published by the Iranian newspaper Shargh, Tehran University professor and pro-reform analyst Sadegh Zibakalam compared Iran’s reformists to a patient in need of a respirator so that they could stay alive until the Iranian presidential election in June 2021. Zibakalam claimed that a last minute “awakening” had led many Iranians to rush to the polling stations in the 2017 presidential election when they did not originally intend to vote. This time, however, not even a miracle can bring back a fraction of the twenty-four million voters who cast their vote for President Hassan Rouhani in 2017. According to Zibakalam, the bitter experience of Rouhani’s second term indicated to voters that electoral politics does not have much of an impact and that the government will continue with predetermined policies regardless of the voters’ demands. This makes bringing reform-minded voters out to the polls exceptionally difficult.

Shortly before the publication of that op-ed, Zibakalam assessed that the vast majority of Iranian citizens would no longer vote for a reformist candidate—including former President Mohammad Khatami—because the failures of Rouhani’s government and the tenth parliament (2016-2020) caused the reformists to lose both their social base and public trust. Zibakalam’s remarks exemplify a growing number of voices among the reformist faction indicating confusion and distress less than a year before the June 2021 presidential election. In contrast with the hardliners, the pragmatist-reformists are headed into the election campaign as the clear underdog.

Since his re-election in 2017, Rouhani has found it more difficult than ever to fulfill his commitments to improve the economy and to expand individual freedoms. Rouhani has staked most of his legitimacy on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and the anticipated economic boom, but those hopes were destroyed by US President Donald Trump quitting the nuclear accord and reimposing sanctions. Additionally, Rouhani’s abilities as a president are limited by the hardliners, led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and he has faced criticism over his foreign and domestic policies from both his hardliner political opponents and his former supporters in the pragmatist-reformist camp.

The intensity of despair among the reformists is reflected in the recent weeks of discourse in the pro-reform media. In a commentary titled “Farewell to reforms,” which was published by the Asr-e Iran news website this month, editor Jafar Mohammadi wrote that the weakness of the Rouhani government and its practical abandonment of the reformist discourse led to the historic and official demise of the reform movement. The low voter turnout in the February parliamentary elections and the resulting victory of the hardliners in a minority vote were only the beginning—a fact which will become more evident in the upcoming presidential election. This is the inevitable fate of the reformist faction which, instead of building a strategic discourse and practical plan of action for real and popular reforms, has relied on the personal credit of individuals and wasted it. Although Mohammadi noted that reforms of “state affairs” are still needed, the reformist faction as we know it is nearing its end after it lost not only its strategy but also its social capital.

As the elections draw closer, the dispute among the reformists regarding the best election strategy is expected to intensify: boycott the elections; run independent candidates more clearly affiliated with them, such as Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif or Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri; or support a moderate conservative candidate such as former Speaker of Parliament Ali Larijani. In the last two presidential elections, the reformists were pushed out of positions of political influence and forced to support pragmatic candidates, such as Rouhani, as the lesser of two evils. Recent parliamentary elections, in which the Guardian Council—a vetting body—disqualified the vast majority of candidates who identified with the reformist faction, have raised serious doubts as to the likelihood of reformist candidates passing the candidate vetting stage.

Subscribe for more from IranSource

Sign up for the IranSource newsletter, which provides a holistic look at Iran’s internal dynamics, global and regional policies, and posture through unique analysis of current events and long-term, strategic issues related to Iran.

Under these circumstances, the prospect of once again supporting a moderate conservative candidate is already drawing criticism from parts of the reformist camp who claim that this strategy has failed in the past. Prominent reformist activist, Saeed Shariati, has recently come out strongly against the possibility of reformist support for Larijani’s candidacy, claiming that Larijiani has nothing to do with the reformists and has even acted against President Khatami’s government in the past. “Anyone who wants to support Larijani should reconsider his own reformism, and reformists who support Larijani should apologize,” Shariati argued.

Another reformist activist, Ali Soufi, also called for the reformists to return to their core principles. In an interview with Arman-e Melli newspaper, he noted that although their influence today is weak, reformists are still responsible for the public. They must clarify their positions and strengthen their connection to society and citizens through a new discourse. The reformist representatives in the outgoing parliament and the government have not served as the voice of society and they left the people to fend for themselves. Rouhani did not implement the demands of his supporters and did not introduce any important changes to government policy. “The people have no voice, and the reformists should be the voice of the people,” he argued.

Calls to re-examine the reformist strategy in light of the difficult reality in Iran were also made among centrist circles of the reformist movement. Hossein Marashi, a spokesman for the centrist Kargozaran party and Khatami’s former vice president, said in an interview with Hamshahri newspaper that reforms are still necessary in Iran, but that political and cultural reforms will lead nowhere in the current climate. What is required is an understanding with “the system” in order to promote economic and social reforms to save the country from poverty and weakness. “It is best for Iran to be a country that is not democratic in the Western sense but is economically prosperous,” Marashi said.

In recent years, reformist intellectuals and political activists have engaged in intense debates regarding the future of the reformist movement in Iran. This debate is taking place in the context of ongoing protests which reflect the increasing radicalization of the Iranian public. The regime’s failure to provide solutions to the public’s economic and social grievances and its political and civilian aspirations, as well as the sense that neither of the two main political camps can resolve the fundamental problems of the Islamic Republic, have contributed to the increasing political radicalization of Iranian citizens. The calls heard during recent waves of protests—“Hardliners, reformists, the story is over”—are clear evidence of widespread frustration with existing political alternatives and reflect the loss of trust in the political system.

In a series of interviews, reformist figures have called for a review of the reformist movement’s strategy so that it can position itself as a relevant alternative to both the hardliners and the radical opposition which undermines the foundations of the Islamic Republic. Abbas Abdi, one of the most prominent reformist thinkers, said in an interview in July 2018 that in order to respond to the growing public criticism, the reformists must launch a process of organizational and ideological reconstruction, involve the younger generation in movement leadership, redefine their relations with the government, and not shy away from criticism of government policy.

Despite the ongoing internal debate, reformists seem to be having a difficult time getting out of their political dead-end because of the ongoing repression by hardline-dominated state institutions and the continuous failures of their political representatives. It is still too early to assess whether they can recover. This will largely depend on the US presidential election results in November and on domestic developments in Iran in the coming months. Iranian elections are very unpredictable and if the reformists come up with an attractive candidate that isn’t disqualified—and especially if Joe Biden wins and the sanctions are removed—it might still be possible to prevent a hardliner victory. On the other hand, a failure to offer a meaningful political alternative may improve the chances of the hardliners in the upcoming elections in the short term. At the same time, growing hardships, the regime’s failure to address them, and the continuing erosion of public trust in the political system, pose a growing challenge to the Islamic Republic over time and may reinforce extreme and populist trends.

Dr. Raz Zimmt is a research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) specializing in Iran. He is also a veteran Iran-watcher in the Israeli Defense Forces. Follow him on Twitter: @RZimmt.

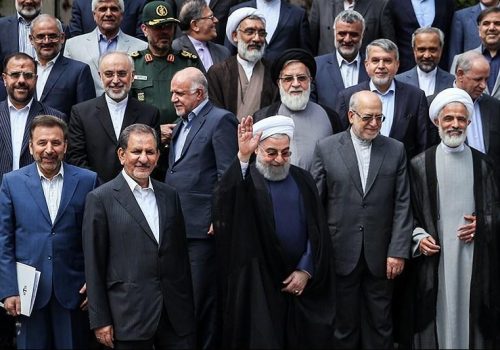

Image: Supporters of former Prime Minister Mirhossein Mousavi, who is a candidate for the upcoming presidential elections stand in front of a poster of him and former president Mohammad Khatami (2nd L) during a pre-election gathering at a stadium in Tehran June 9, 2009. REUTERS/Damir Sagolj