The Hazara community in Afghanistan is stuck in the middle between Iran and the Taliban

With the Taliban having come to their second iteration of power and the announcement of a newly-formed government in Afghanistan in recent weeks, several stakeholders will see a shift in their relationships, namely Iran and Afghanistan’s ethnic Hazara minority—an overwhelmingly Shia population that is influenced by Iran and contains very small pockets of Sunni and Ismaili adherents.

As the Taliban works to cement its country-wide power, the Sunni Islamist movement faces a hurdle in persuading the Hazara community—a sizeable 20 percent of Afghanistan’s population—that it has a place under its rule despite a history of brutal and systematic marginalization under the previous Taliban regime during 1996-2001. The Taliban, Hazaras, and Iran will have to navigate an uncertain future that has been marked by a contentious relationship between the three stakeholders until the present day.

Iran and the Taliban reached an inflection point in 1998, when the militant group allegedly killed nine Iranian diplomats within the Iranian consulate in Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan. The event almost led to Iran going to war with Afghanistan, but instead pushed Iran into strategically backing the Northern Alliance as the main Taliban opposition while supplying intelligence to the United States to help oust the Taliban during the 2001 invasion.

However, in recent years, schismatic tensions between Iran and the Taliban have appeared to be replaced by politically rational calculations based on mutual interests—marked recently by two high-profile Taliban delegation meetings in Tehran in January and July of this year. This stems from a more social media- and diplomatically-savvy Taliban—they have become more politically competent at their office in Qatar within the past eight years—although they still resorts to their old ways of repressing the Afghan people with draconian laws.

As the regional power next door, Iran has sought to expand its sphere of influence within Afghanistan (even during the two-decade tenure of the US). Iranian ambitions have dealt with a historically hostile Taliban relationship that view any internal Iranian connections with suspicion.

For example, the majority of Hazaras belong to a historically persecuted Shia sect and, therefore, share a commonality of faith with the clerical establishment in Iran. This commonality has served as a direct linkage between Iran and the Hazaras, culminating into instances of Tehran using its soft power under the guise of collaboration. One such example is the formation of the Fatemiyoun Brigade, a Shia militia, in the 1980s to counter external threats facing the then newly-formed Islamic Republic of Iran, such as the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq War and the 1989-1992 Afghan Civil War.

As a result of being seen as heretical by the Taliban and systematically brutalized since the 1990s, hundreds of thousands of Hazaras have fled to Iran, where many young Hazara men have become Brigade recruits—a phenomenon that increased during the onslaught against the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS). With the onset of ISIS in Iraq and Syria, Iran restructured the Fatemiyoun as a professionalized proxy force directly under Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) command. With the conflicts in Syria and Iraq at a somewhat stable point, Iran now seeks to cement the Fatemiyoun as its proxy within a new Afghanistan.

The Fatemiyoun Brigade

The Fatemiyoun Brigade is primarily rooted from Afghan refugees of Hazara ethnicity in Iran, who are often forcibly encouraged to join. Estimates from a 2019 US Institute of Peace report claim there are between forty thousand and sixty thousand members of the brigade. The number of Fatemiyoun troops Iran deployed to support Bashar al-Assad in Syria to fight ISIS is estimated to be in the tens of thousands. Internal reports have made indications of Iran offering Hazara individuals and their families coercive incentives, such as legal protections, citizenship, and payment in return for serving within the Fatemiyoun. However, many are intimidated into joining by threats of deportation and arrest. This seemingly contractual relationship creates an air of uncertainty in terms of the level of allegiance Iranian-involved Hazaras hold towards their religious custodians.

While the Fatemiyoun became outlawed under the new Taliban regime, the governments of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani made little to no public acknowledgment of their presence within Afghanistan, with reports that recruitment continued under the nose of their respective presidencies. In a relatively rare high-ranking comment on the Fatemiyoun Brigade, Rahmatullah Nabil, the head of Afghanistan’s intelligence agency from 2010-2012 and 2013-2015, stated in February 2020 that the Fatemiyoun did not provide an “immediate threat to Afghan national security,” noting that several thousand members had returned from the Syrian frontlines.

According to senior officials of Afghanistan’s former government, Iran has reportedly sent thousands of Fatemiyoun fighters, who served in Syria and Iraq, back to Afghanistan with weaponry and money from the IRGC to allow for a rapid mobilization network to defend Shia interests within the country, if necessary. However, this sentiment contrasts with those who view the Fatemiyoun as skilled combat veterans against ISIS and those within the Syrian conflict who have received IRGC training, creating possible concerns amongst the Taliban that there may be an Iran-linked, Fatemiyoun-led assault against the newly formed government.

Tehran has not announced its policy regarding the Fatemiyoun Brigade operations within Afghanistan, with the exception of former Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif’s statement in December 2020. Zarif, referring to Ghani’s government at the time, stated: “The Afghan government is fully informed that we are prepared to help the Afghan government regroup [the Fatemiyoun] under the leadership of the Afghan National Army in the fight against terrorism.”

Zarif’s statement was made within the broader call for more Shia offensive coordination towards fighting ISIS’s offshoot Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISIS-K) within Afghanistan.

While this statement was directed towards ISIS as Iran’s prime enemy of Sunni extremism, there is no indication that Iran would not use Fatemiyoun fighters within Afghanistan to combat the Taliban, which could remain a possibility if Tehran sees opportunities to strike at the main Sunni-extremist actors within Afghanistan.

Taliban aims to be kinder to the Hazara minority—for now

During the first iteration of Taliban rule from 1996 to 2001, massacres against the Hazaras and systematic discrimination were the norm. Taliban fighters tortured and murdered nine Hazara men during the summer offensive after taking control of Afghanistan’s Ghazni province in early July, eerily echoing similar previous mass killings of Hazaras by the Taliban in 1998.

The Taliban’s political and strategic metamorphosis from the 1990s to the present may reset Iran and the Taliban’s volatile relationship, especially while Tehran seeks to turn its attention towards the east. As the custodian of Shia across the region, Iran’s understands that Hazaras cannot be secure without their representation at the local level under the Taliban, therefore requiring a level of engagement between Tehran and Kabul to promote the interests of Shias within Afghanistan.

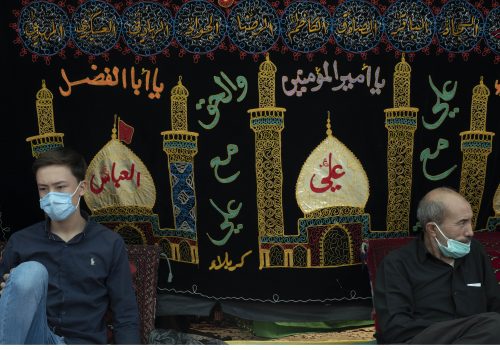

Since seizing Kabul on August 15, the Taliban have not interfered with Shia religious festivities such as Ashura and have assured the Hazaras—targeted by ISIS-K attacks in recent years—of their safety. However, the Taliban has attacked Hazara cultural symbols. Most notably, the Taliban allegedly destroyed the statue of Hazara leader and anti-Taliban icon Abdul Ali Mazari in Bamiyan province in mid-August, whom the group executed in 1995. Mindful of the past and recent atrocities, many Hazaras are treading with hesitation as Taliban communications seek to ease tensions on the surface level. Reinforcing Hazara concerns, a late August attack by the Taliban resulted in the shooting and subsequent deaths of fourteen Hazaras, which included Hazara military and civilian personnel, in Daykundi province.

Winning Hazara trust under the Taliban may fall on rarities such as Mawlawi Mahdi, one of very few Hazaras who joined the group’s ranks as a high-ranking commander to bridge this gap. In April 2020, Mahdi publicly stated in a rare Taliban video message (which sought to secure Hazara-Shia support and membership) that “they should not be worried” under a second Taliban tenure and that “this is a government for all Muslims.” However, the July and August killings of a known total of twenty-three Hazaras by the Taliban showcases a potentially different outcome reminiscent of a recent past still entrenched in the memory of the Shia minority.

Hazara leadership and localities and the Taliban government need to reach a public-political compromise. Nevertheless, Iran remains a major stakeholder in any relationship-building where it holds the reigns of the Shia minority. Mixed messaging from Taliban leadership—ranging from ensuring safety and new beginnings with the Hazara to messages of aggression and acts of brutality—makes a sustainable relationship more unlikely. An approach centered on Hazara inclusivity would aid in country-wide stabilization and increase strategic relations, especially with an eagerly east-looking Iran. Additionally, the destabilization threat of ISIS-K, with deadly bombings such as the August 26 Kabul International Airport attack and, more recently, the bombing of Eid Gah mosque on October 4, will require a unified front.

Despite internal instability, the Taliban appears to be making noteworthy trade developments with Tehran. On October 4, an Iranian delegation met with Taliban leadership in Kabul to seek strengthened trade ties, with significant outcomes being co-development of shared border crossings, streamlining of imported Afghan fuel shipments, and construction of an Afghan-Iran gas pipeline. Given that Iran appears to be easing its stance toward the Taliban, this may be a more realistic outcome as a fledgling Taliban government seeks to cement its legitimacy across Afghanistan and externally.

However, the Hazara continue to largely bear the role of serving as human capital for Iranian interests while being caught up with mixed messaging from the Taliban. Iran and the Taliban need to fully grasp how bridging their historical divides, with the Hazara as real and present stakeholders, can lead to each of these parties thriving within a chaotic post-US Afghanistan.

Saumaun Heiat received his MA focusing on International Development and Middle East Studies from the Elliott School of International Affairs. He currently works at Chemonics International, Inc. as a Senior Associate on the USAID-Iraq Durable Communities and Economic Opportunities (DCEO) Project. Follow him on Twitter: @saumaun1.

Further reading

Fri, Aug 20, 2021

Iran spent years preparing for a Taliban victory. It may still get stung.

IranSource By Borzou Daragahi

Iran’s relatively sanguine stance toward the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan demonstrates, above all, the strides Tehran has made in improving its relations with the armed insurgent network that was once considered a mortal enemy of the Islamic Republic.

Tue, Feb 16, 2021

Iran-Taliban growing ties: What’s different this time?

IranSource By

Regional cooperation might be the only solution to reach a lasting peace for Afghanistan and, in that regard, Iran may be able to help.

Fri, May 15, 2020

Afghan migrants: Unwanted in Iran and at home

IranSource By Fatemeh Aman

Tensions between Iran and Afghanistan are rising over the alleged drowning of Afghan migrants in the Harirud River by Iranian border guards in early May.

Image: Hussain Rahimi, 23, an ethnic Hazara, from the Shi'ite community, holds a picture of his sister Golsom, who was killed in a school bombing earlier this year, during an interview with Reuters, in Kabul, Afghanistan October 18, 2021. Picture taken October 18, 2021. REUTERS/Jorge Silva