Five years of Russian aid in Syria proves Moscow is an unreliable partner

Five years ago, the Russian Defense Ministry established its Center for Reconciliation of Conflicting Sides (CRCS) in Syria. More famous for negotiating surrender deals with opposition groups, the CRCS has grown to become the main player in Russia’s ‘softer’ engagement in Syria: its provision of humanitarian aid. By its own reporting, the CRCS has conducted 3,090 missions to 731 communities around Syria between February 2016 and February 2021. A key node in Russia’s shadow aid system, which has undeniably provided relief to some communities, the CRCS’ actions have also been shallow, inconsistent, and lacking in long-term commitment, ultimately making Russia an unreliable partner for the Bashar al-Assad regime.

Making money and buying influence: How Russia views aid

As with my previous piece on MENASource, this study is also based on publicly available information from the Russian entities identified in this article. Although this limits the findings of this study by potentially missing unreported actions, or the data being skewed towards how each entity wants to portray its public image, it nonetheless provides a window into how Russia wants the world to view its aid efforts in Syria.

Since Soviet times, Russia has long viewed the provision of aid as a tool to improve its image as a credible global power. However, it was not until 2007 that Russia released its first ever concept on foreign humanitarian assistance formalizing this view. Just two of the nine overarching goals in this policy were linked to humanitarian action as the West knows it: aiming to “eliminate poverty” and addressing “the consequences of humanitarian, natural, environmental, and industrial disasters and other emergencies.” The others continued the Soviet legacy of seeking to use aid to repair Russia’s standing in the world and provide economic benefit to the homeland. After Russia’s first year in Syria, Russia became even more explicit with its intentions about the use of humanitarian aid, stating that it was an “integral part of [its] effort to achieve foreign policy objectives” in 2016. In other words, humanitarian aid had become a key soft power instrument.

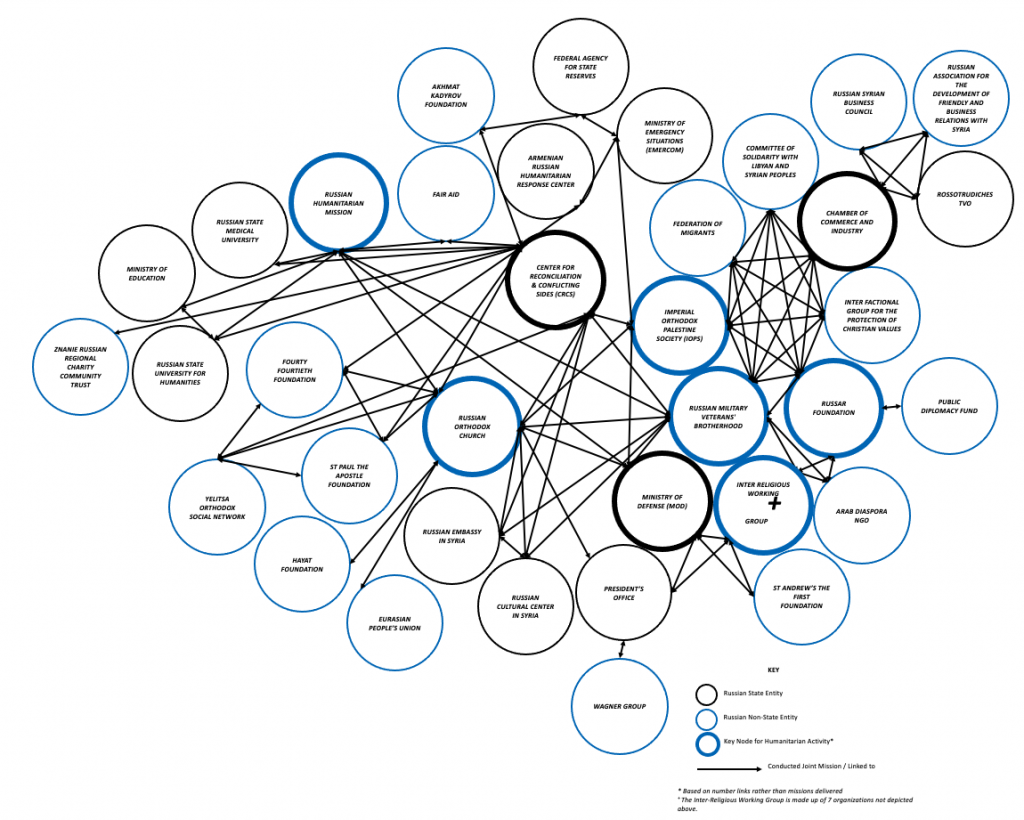

Russia’s humanitarian ecosystem: Re-enforcing soft power

This may not appear much different than how other countries use aid to promote their narratives. But, outside of the Russian context, there is typically some separation between state power and humanitarian efforts. For example, the US uses the United States Agency for International Development to support hundreds of humanitarian agencies and non-governmental organizations in Syria rather than directly distributing aid through state institutions. In turn, these entities are accountable to their own boards, monitoring procedures, and other government donors if they receive funding from elsewhere. Many entities also collaborate with the United Nation’s (UN) cluster system, further diluting the influence of soft power.

In contrast, Russian aid delivery is predominantly conducted by state institutions. In Syria, 81 percent (3,180 out of 3,897 deliveries) of all reported Russian aid were delivered or supported by Russian state institutions (Figure 1). Although non-state entities made up the remaining 19 percent, many of these entities are informally accountable to the Kremlin through senior leaders within these organizations. Russian aid providers also rarely integrate into the UN-led humanitarian coordination system in Damascus. This reliance on and influence from the state ensures that Russia’s soft power is protected from outside influence.

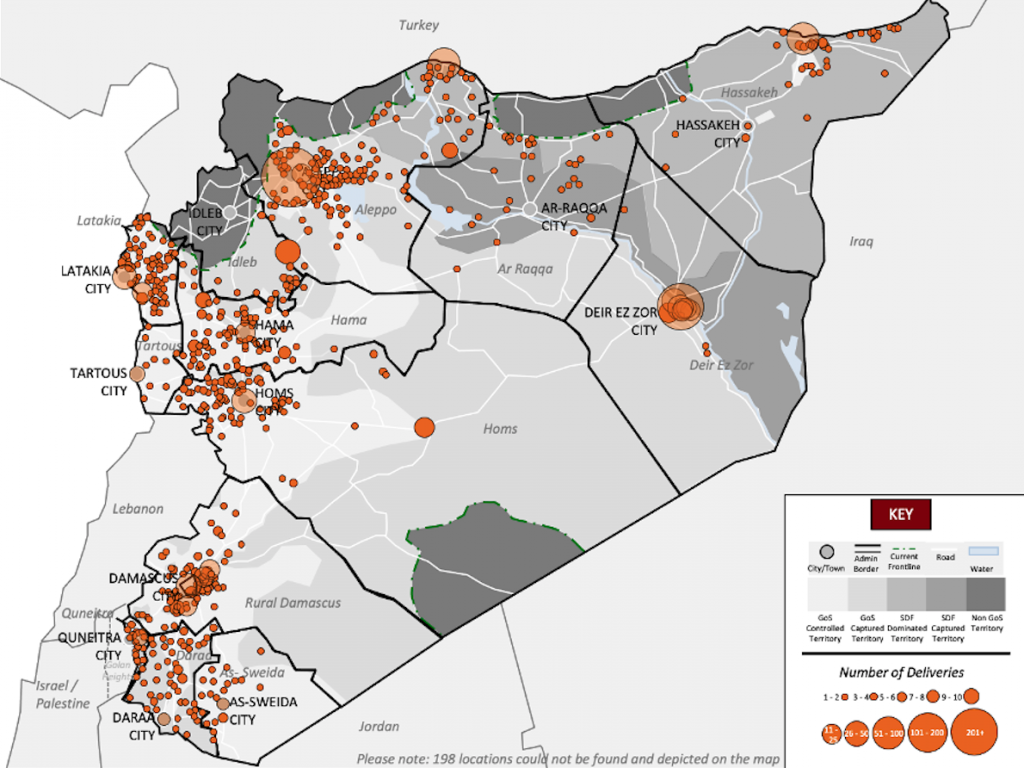

Data on five years of Russian aid in Syria

When exploring the data on CRCS aid deliveries in Syria, three main features emerge (Figure 2). Firstly, Russian aid provision in Syria is shallow. Of the 731 communities that CRCS delivered aid to in the past five years, 98 percent (717 communities) were symbolically served by one-off or limited visits. Just 2 percent of locations could be said to have seen sustained support: Aleppo (865 visits), Al-Salhiyah (298), Quamishli (seventy-five), Ain al Arab (sixty-nine), Marrat (forty-seven), Khasham (forty-two), Latakia (forty-two), Mathloum (forty), Al Husainia (thirty-seven), Damascus (thirty-two), Hatla (thirty-one), Homs (thirty-one), Abu Thuhur (thirty), and Deir Ez Zor City (twenty-four). But, even then, aid stopped being delivered to three of these locations in December 2018 (Abu Thuhur), March 2020 (Ain al Arab), and November 2020 (Damascus). Even at its best, Russian aid cannot be relied on.

Second, Russia’s aid to Syria lacks commitment. Over the past five years, Russian aid in Syria has declined, despite the needs of Syrians increasing over the same time period. While there have been periodic increases at various points, these have typically corresponded with Russia and the Assad regime achieving objectives important to them. For example, after the Syrian government captured Aleppo in late 2016, Palmyra in March 2017, and Deir Ez-Zor in November 2017, and when Russian and Syrian troops were able to access Northeast Syria after a deal with Kurdish-led authorities in November 2018. In contrast, following the Syrian government capture of so-called undesirable areas—such as Eastern Ghouta in April 2018, southern Syria in July 2018, or the various campaigns in northwest Syria from April 2019 onwards—Russian aid provision in Syria typically declined. Mirroring Syrian regime attitudes towards those areas, which punished some while rewarding others, the fluctuations in aid provision were also likely related to balancing various Russian goals in the conflict, as well as prioritizing its competition against Iran and US influences.

Finally, Russian aid is inconsistent. Focusing on CRCS’ two main provisions, medical and food support, monthly levels regularly fluctuated. Indeed, since March 23, 2020, the CRCS has inexplicably stopped conducting medical missions to Syria, which is when the country arguably needed help the most in its fight against COVID-19. Russian food aid is not much better, being rudimentary at best; little more than small plastic bags filled with basic supermarket items, such as tins of tuna, rice packets, and small bags of flour.

Recommendations

It is clear from Russia’s own data that their aid efforts do not have the best interest of the Syrian people in mind and operate well below the standard of the UN-led response to the country. However, while Russia’s humanitarian actions on the ground appear significant, taking a wider view, Russia’s investment in Syria’s humanitarian space is extremely modest. In 2020, for example, Russia invested just $23.3 million into UN-coordinated aid compared to the $3 billion the European Union states and US contributed. Russia’s actions on the ground clearly do not make up for this shortfall but has led Russia to become overconfidence in its ability to provide aid, something that should not be underestimated. However, potential opportunities exist to respond to Russia’s instrumentalization of aid, such as:

- Cautiously engaging with Russia. Not negating the significant harm caused by Russia’s actions in Syria, it is important to recognize that some of Russia’s humanitarian actions have been constructive. For example, the prolonged provision of water to civilians around Deir Ez-Zor (December 2017 to April 2018) after its capture were arguably lifesaving. These limited examples could be used to engage Russia in meaningful discussions around a common starting point, as well as educate how Russia can positively contribute to the humanitarian situation in Syria. Through this, Russia could receive the recognition from the international community that it has long craved, while still allowing the international community to protect itself from inadvertently legitimizing the rest of Russia’s problematic actions in Syria, which should continue to be called out.

- Encouraging Russian aid to be more transparent. Ideally, this would encourage Russian aid entities to participate in the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs-led system in Syria, which, despite its issues, is one of the more robust coordination mechanisms for effective aid delivery. Alternatively, efforts could be made to better reveal Russia’s aid activities in Syria. A public dashboard by the Foreign Ministry’s Rossotrudnichestvo, a government agency responsible for administering cultural exchange and some foreign aid, has been a good start. But it is still lacking as Russian aid activities in Syria for 2020 are underreported by 91 percent, showing forty deliveries compared to the 447 found by this study. Until information about Russia’s aid activities are more accessible to the wider humanitarian community, Russia will not be taken as a serious actor.

- Diluting state influence in Russian aid. Efforts should focus on building the operational-level capacity of non-state Russian humanitarian entities to international standards. After all, many working on the ground are humanitarian professionals who, like their western counterparts, are seeking to make a difference. These people will be the cornerstone of any deep improvement in Russian humanitarian action. While the trade-off for Russia will be the weakening of influence in non-state aid efforts, Russia’s reputation on the global humanitarian stage could be improved.

Jonathan Robinson is a researcher with nearly a decade of experience working in the Middle East, including Syria. He focuses on conflict analysis, humanitarian access, and aid worker security. His views here do not represent his current or previous employers.

Image: Workers are seen unloading humanitarian aid sent from Russia to the Syrian government in this handout photograph distributed by Syria's national news agency SANA on May 28,2013. Two planes loaded with 30 tons of humanitarian aid arrived to al-Bassel airport in lattakia city from Russia on Tuesday, SANA said. REUTERS/SANA