ISIS is defeated. What becomes of the ‘Cubs of the Caliphate’ in Iraq?

In the space between the tawny brown desert and the crystal blue sky, a boy wears a secondhand military uniform two sizes too big—his small hands gripping a gun taller than his body. He’s only nine.

What becomes of this boy and the thousands like him in Iraq as the terrorist organization that enlisted him turns to rubble? Over its lifespan, the recruitment of male child soldiers became an integral component of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) operations. Adult members separated children from their families, at times exposing them to the brutal murder of their parents. In the aftermath, ISIS militants whispered in the children’s ears the indisputable justification for their suffering: they were not believers.

Abducted, coerced, or manipulated, these children were herded like cattle to education and training centers. ISIS members molded their trauma and vulnerability into obedience and rage. In place of candy, they doled out Captagon pills, an amphetamine used to dull fear and embolden those who consume it. Children donned suicide belts and marched to the front lines as human shields. ISIS called them the “Cubs of the Caliphate”—the army of the future.

Due to their malleability, children are a frequently exploited strategic source of manpower. Utilizing the same tactics as other militant and terrorist organizations, ISIS recruited children through three primary mechanisms. Most significantly, the organization perpetrated mass abductions of children. Recruiters also coerced them through deception and manipulation, often making false promises of compensation or payment. Some cubs entered the lion’s den without the need for direct recruitment. A child’s family member or friend joined ISIS and spoke highly of bravery and power. They wanted in, too.

Mechanisms of indoctrination

In Iraq, frequent exposure to violence from an early age facilitated the recruitment process. The endemic dissemination of ISIS propaganda not only desensitized children to brutal acts of violence but also normalized such violent measures as means for dealing with enemy “infidels.” Children as young as three even appeared in beheading and execution videos—sometimes, as the executioner. With a young mindset manipulated, indoctrinated children found little trouble with the ideologies of ISIS.

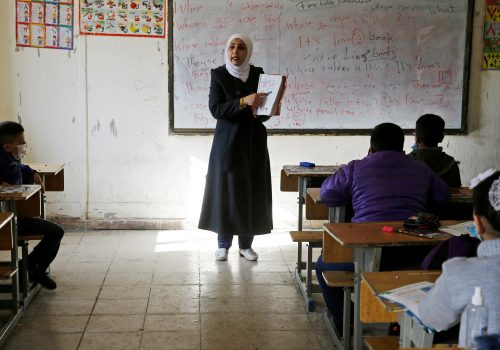

The organization’s recruitment processes relied heavily on institutionalized systems. The extensive control and government-like presence of ISIS facilitated a system of schools and training centers that divided children into groups and subjected them to Islamic education tailored for the indoctrination of extremist values and continued exposure to violent propaganda. After “going through the system” of established ISIS pedagogical institutions, children were forcibly conscripted into the group and received combat training at specialized centers. They learned how to “use light and medium weaponry, shoot, dismantle and reassemble weapons, go on raids using live ammunition, and do other tasks for the group, such as logistics, spying, guard duties, manning checkpoints, and forced labor.” Youth recruited without attending ISIS schools underwent courses at so-called sharia camps, where they received intensive indoctrination and physical endurance training. After training completion, the group deployed children based on their performance during ISIS’s “core curriculum.” Those perceived as less talented—and therefore expendable—were most often chosen to carry out suicide attacks.

Current treatment of child soldiers in Iraq

Now, as ISIS crumbles and its cubs are released, these children lie in purgatory as the world decides if they are victims or perpetrators.

Without a doubt, some children did carry out heinous acts of torture and murder on behalf of the group. If deemed necessary, they can be prosecuted under international law with factors like age and forced conscription taken into consideration. However, prosecution is neither justice nor a remedy for the harms perpetrated against these children. Imprisoning them will not help rebuild Iraqi society. Instead, it further stigmatizes former child soldiers, hindering their acceptance by their families and communities.

Nonetheless, Human Rights Watch estimates that the Iraqi and the Kurdistan Regional Government detained and charged 1,500 children with terrorism for alleged affiliations with ISIS. Most of the charges rest on a nebulous legal basis and coerced confessions obtained through torture. Tried as children, government authorities have sentenced most of them to prison. Not only are these blanket charges unethical, but they are also counterproductive. While imprisoned, children and adolescents are likely to experience trauma, confusion, societal rejection, and self-dissociation. Inevitably, prisons facilitate further recidivism and limit mechanisms for rehabilitation.

Healing ISIS’s cubs is not only just, but it also has wider benefits for Iraqi society and regional security. Child soldiers are less likely to hold stable jobs, build families, and participate in civic life. Without successful reintegration, the indoctrination and training that warped their childhood will carry over into adulthood, making former child soldiers more vulnerable to extremist activity in the future. Letting these boys and girls become a lost generation is disadvantageous to the sustainability of international counterterrorism efforts. It is in the interest of the United States and the wider international community to mitigate this outcome and create a stable and prosperous Iraq.

Means of reintegration

The alternative to prison is a framework for child soldier reintegration, the most widely used of which is disarmament, demobilization, and rehabilitation (DDR). This framework requires that teams identify the targeted children, remove their weaponry and publicly destroy it, and place them in Interim Care Centers (ICCs) until they release them to their families. ICCs focus on fulfilling a child’s hierarchy of needs by ensuring physical wellbeing, daily structure, therapy, educational activities, and vocational skills training.

On paper, DDR proves effective in much of the world. In practice, however, it scrapes by as a foundation. To effectively implement reintegration programs for former ISIS child soldiers, DDR must be individualized to the specific cultural and religious contexts of former strongholds and added upon. Trauma-informed psychologists must be at the forefront of all established reintegration processes. After locating parents, reintegration teams must transport the children from ICCs to their homes. Orphans should be placed with next of kin. Those whose families hold ties to ISIS can be put under the state’s care in long-term facilities capable of supplying adequate psychological, educational, and physical support.

In cooperation with local religious and community leaders, experts can educate families and communities on the debilitated states of their children, the effects of violence and extremism, and mechanisms of proper emotional support. Islamic teachers and influences can redefine religion for indoctrinated children, shifting away from extremism and toward moderation.

Communities, too, should be prepared for the reintroduction of former child soldiers without ostracizing or stigmatizing their existence or return. Intra-group dialogue among leaders and citizens should emphasize that these children are not innately “bad” but rather were manipulated into a war created by adults. Even those who enlisted voluntarily were “triggered by a life of depravity and suffering.” Tolerance and reconciliation cannot be taught nor forced. However, understanding that the children suffered enormously at the hands of ISIS is the first step in generating empathy—the foundation of community reconciliation.

Child soldiers are at increased risk of developing mental disorders, specifically depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Follow-up psychosocial support is perhaps the most vital element of effective reintegration. Most DDR programs have failed to provide adequate extended care, jeopardizing the reintegration process. The Iraqi government and civil society must systematically check in with former child soldiers in the long term through in-person counseling and social work visits. This way, programs can further their understanding of the reintegration process on the ground and in real time.

Heal the children

In the aftermath of sanctions, three wars, and continued violence, Iraq’s infrastructure and established child services networks remain debilitated. The reintegration of child soldiers is an extensive and long-term project that demands more than Iraqi institutions can give. Iraqi professionals and aid agencies have flocked to neighboring countries, and donors continue to roll back their financial support for civil society programs. Countries such as the US should encourage and offer financial and material support for the Iraqi government on the condition that it shifts away from the imprisonment of child soldiers and instead focuses on reintegration programs. DDR practices should be coordinated nationally and take advantage of existing structural institutions. With increased funding, the government can scale existing local-level child protection mechanisms and community-based programs to provide trauma-informed practices for returning child soldiers.

The reintegration of child soldiers is an intensive and lengthy process. Effective implementation requires a concerted effort from local public and private spheres, humanitarian organizations, and international coalitions. ISIS raised their cubs to be bombs, ready to be activated at a moment’s notice. We cannot let years of our time and trillions of dollars of counterterrorism measures go to waste. Heal the children. Defuse the bomb.

Heba Malik is a former Young Global Professional with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. Follow her on Twitter: @HebaJMalik.

Image: Ismail, an Iraqi boy who managed to escape from the Islamic State-controlled Jarbuah village near Mosul and arrived at the Kurdish Peshmerga military camp, squats against a wall while recounting his experience, in Iraq October 28, 2016. REUTERS/Ahmed Jadallah