Islamic Resistance in Iraq appears to be responsible for attacks in the country and there’s no end in sight

Ahead of Antony Blinken’s visit to Baghdad on November 5, Iraqi militants made it clear that they were unhappy about the prospect of the US secretary of state coming to town.

“The visit of Antony Blinken, the son of a Jew, is not welcome in Iraq,” read a post circulated on social media by Abu Ali al-Askari, a pseudonym used by a senior official in Kataib Hezbollah, an Iran-backed armed group. The message also threatened to ban US citizens from Iraq and close the US embassy, adding that “we will achieve this in our own, non-peaceful way.”

While posting such threats, Kataib Hezbollah—which is designated by the US as a terrorist organization and is officially part of the Iraqi security forces—has not directly claimed responsibility for rocket and drone attacks that have taken place since October 7 against US personnel in Iraq.

Instead, a group called the Islamic Resistance in Iraq has named itself responsible for most of the attacks, posting claims on a Telegram channel called Iraq Flood (“Tufan al-Iraq” in Arabic), mimicking the name of Hamas’ al-Aqsa Flood (“Tufan al-Aqsa”) operation. The majority of these attacks have targeted the Ain al-Asad military base in Anbar province, the Harir airbase near Erbil in the semi-autonomous Kurdistan region, and the Conoco gas field and al-Tanf base in neighboring Syria. On November 9, militant groups likely carried out an Improvised Explosive Device (IED) attack on a ground convoy belonging to the US-led anti-Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) coalition near Ninewa province’s Mosul Dam, indicating a widening of tactics.

On November 17, a defense department official said that US forces in Iraq and Syria had been attacked sixty-one times since October 17, with the figure split roughly in half between the two countries. The Pentagon had previously blamed “Iranian-backed groups in Syria and Iraq” for these attacks.

There are around 2,500 US troops in Iraq at the invitation of the government in Baghdad and nine hundred in northeast Syria to support operations against remnants of ISIS. The US has responded to the attacks by carrying out at least three rounds of airstrikes in Syria on what it describes as facilities “used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Iran-affiliated groups.”

On November 21, the Islamic Resistance in Iraq announced the death of Fadil al-Maksusi as a “martyr” in the “righteous battle against the falsehood incarnated by the American occupying forces in Iraq.” Later that same day, a defense department official told journalists that the United States and coalition forces were targeted at Ain al-Asad and US forces “responded in self-defense against those who carried out the strike.” The situation escalated the following day, when US Central Command confirmed that it carried out precision strikes on two facilities at a separate location, which it said were a “direct response to the attacks” on November 21 that “involved use of close-range ballistic missiles.” A post on a Kataib Hezbollah-affiliated Telegram channel said five of its men were killed in the strikes.

What or who comprises the Islamic Resistance in Iraq is left deliberately vague; the brand’s opacity provides each armed group a level of plausible deniability. Nonetheless, leaders of individual armed groups have made public statements clearly linking attacks on US interests in Iraq to Washington’s support for Israel and its military operations in the Gaza Strip, which have killed more than thirteen thousand people and prompted outrage across the Middle East.

“There will be no end to the operations of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq unless the [Israeli] attacks on Gaza stop, and no ceasefire for the US occupation in Iraq unless there is a real and binding ceasefire for the enemy on our people in Gaza,” tweeted Abu Alaa al-Walaei, head of the Kataib Sayyid al-Shuhada group, which is part of the Iraqi state-backed Popular Mobilization Forces. Al-Walaei was added to the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (OFAC) specially designated nationals list on November 17.

Despite the US issuing recent warnings to Israel over high civilian casualty numbers in Gaza, the overwhelming perception in Iraq regarding US support for Israel was already cemented in the days after Hamas’ October 7 assault, meaning that the attacks against US interests in Iraq and Syria will likely continue.

“The attacks are going to increase day after day, and things are going to escalate,” said an Iraqi official in Mosul to me after the IED attack.

This does not mean that the attacks and US counter-attacks will necessarily prompt an escalation to the level of Iraq or that state-supported militant groups will become directly involved in a broader conflict with Israel. In the Syrian civil war, Iraqi brigades easily crossed the long land border to fight on the side of Bashar al-Assad’s government. That is not an option in the case of Gaza.

Iraqi military officials believe that the militant groups are likely taking action in order to defend their positions as vocal critics of Israel and self-proclaimed defenders of Palestinians, as well as to bolster local support over a highly emotive issue.

“They have talked so much about their hostility to America and how they want to liberate Jerusalem,” one Iraqi military official told me. “If they stay silent now, it will be really, really, really embarrassing for them.”

The Pentagon has described the recent attacks as “harassing.” Still, they have not caused the sort of destruction wrought by the IRGC ballistic missile attack on Ain al-Assad following the 2020 US assassination of Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani and PMF commander Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis in Baghdad. To date, all of the roughly three dozen US personnel injured in the rocket and drone attacks—some with traumatic brain injuries—have returned to work.

The attacks, while not amounting to nothing—the US and UK governments have both pulled out all non-essential diplomatic staff from their Baghdad embassies and Erbil consulates as a result of the precarious security situation—do not indicate that a full-blown conflict on Iraqi soil is on the cards.

Instead, they are reminders that Iraq can be made a much more difficult place for the US and Americans to operate because of its policies towards Israel and the Gaza Strip. The attacks appear to be designed to up the ante without the intent of directly killing large numbers of US troops, which would likely attract a more forceful response from Washington.

The current situation also presents opportunities that resistance groups in other countries can take advantage of. Beyond praising Iraqi actors, they can expand their opposition to the US’s stance on the Gaza war to include the latter’s military footprint across the entire region.

“The Islamic Resistance in Iraq has decided to attack the US bases in Iraq and Syria because the US is the one leading the killing in Gaza,” said Lebanese Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah in a recent speech on November 3. “This is a wise and blessed and great decision by the leadership of the Islamic Resistance in Iraq.”

It is worth mentioning that this attack pattern is not new and this sort of activity occurs during periods of heightened regional and domestic tensions. There had been a period of calm prior to October 7, but in the past, US interests in Iraq have been repeatedly attacked by Iran-backed armed groups. One such period was during the Iraqi government formation process after the 2021 parliamentary elections, in which an Iran-backed alliance was pitted against others viewed more favorably by the West.

The armed groups also have more to lose from further instability in Iraq than they have in the past, which likely acts as a deterrent from carrying out actions that could drag the country into a more intense conflict. The country pulls in around $9.5 billion monthly in revenues from oil sales, and the relative calm of recent years has allowed the opening of shops, restaurants, malls and the expansion of crude oil production that further enriches the political and business elite. The establishment of revenue streams is not something powerful Iraqis wish to disrupt.

All the same, the persistence of the attacks highlights the inability of the governments in Baghdad and Erbil to prevent strikes on US interests in Iraq and the absence of a state monopoly on force.

An Iraqi military spokesperson released a statement in a WhatsApp group on October 23 describing the attacks as “unacceptable,” and said that Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani ordered security forces to pursue the elements responsible for these attacks.

“[The foreign forces’] work is regulated by the Iraqi government and understandings that Iraqi diplomats have signed,” the statement said. “Therefore, the security and the safety of these facilities are a redline. Breaches to security and safety cannot be tolerated.”

But the attacks have clearly persisted since then. It may be the case that the Iraqi government cannot pinpoint exactly who is launching the attacks or where the attacks are coming from, making them harder to thwart. There is a security vacuum in large swathes of Iraqi territory because of long-standing territorial disputes between the central government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government. This territory, stretching through Ninewa, Kirkuk, Salahaddin, and Diyala provinces, is not fully secured by either federal or Kurdish security forces and can be easily used by armed groups to plan and carry out attacks.

“The government and its security forces are working hard on the field to prevent these attacks and they have been successful in thwarting a score of them,” Farhad Alaadin, a foreign affairs advisor to the Iraqi prime minister, told me.

Iraq’s armed groups have plenty of reasons not to want to ignite a conflict. Indeed, they would want to resist being dragged into one if they continue to hit the United States (as these armed groups say they will) and the US decides to respond more fulsomely—as it appears to be doing in its November 22 strikes on Jurf al-Sakhar, a known Kataib Hezbollah base. Tensions have risen much higher in Iraq in the past, such as after Soleimani’s January 2020 assassination. A period of grinding back and forth followed, including the killing of at least three US and coalition forces on March 11, 2020 in rocket attacks at an Iraqi military base, which also prompted US strikes on Jurf al-Sakhar two days later, without a wide-scale, multi-front conflict inside Iraq. Many Iraqi armed groups have a political presence in the Baghdad government; they likely favor maintaining influence in a state that is not distracted by a bigger conflict on home soil over escalating in response to more intense US attacks.

Iraq is witnessing part of the regional fallout from the Israel-Hamas war, and Iraqi bases housing US troops are feeling that most forcefully. While the grinding back and forth of a militant attack and US counterattack may well continue for some months, there is too much else at stake in Iraq for the actors involved to draw the country into full-blown conflict.

Lizzie Porter is a Middle East correspondent based in Istanbul. Follow her on X: @lcmporter.

Further reading

Wed, Nov 15, 2023

I covered the battle against ISIS in Mosul. Gaza’s challenges will make it look like child’s play.

MENASource By Arwa Damon

If there is something to be drawn from those lessons, it is that what Israel is doing right now will secure anything but peace and stability.

Tue, Nov 7, 2023

Iraq is at a crossroads. Will it choose its Shia militias or relations with the US?

MENASource By Sarkawt Shamsulddin

Iraq is facing a high-stakes balancing act that carries profound implications for its relations with the United States and regional stability.

Fri, Nov 17, 2023

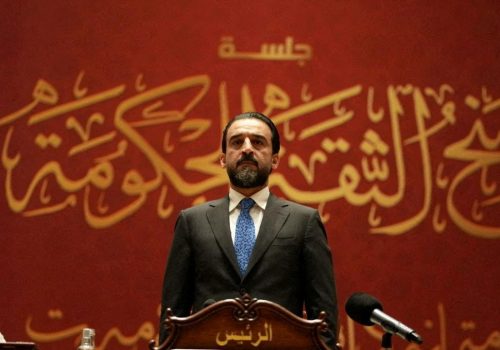

Iraq’s parliamentary speaker was removed. What’s next for the country?

MENASource By Abbas Kadhim

The current crisis dates back to May 2022, when Mohamed al-Halbousi removed one of his bloc’s members from parliament.

Image: Mourners carry the coffins of Iraq's Kataib Hezbollah fighters who were killed by US airstrike in Jurf al-Sakhar, south of Baghdad during a funeral in Baghdad, Iraq November 22, 2023. REUTERS/Thaier Al-Sudani