Jordanians are protesting again. It’s time for economic and administrative reforms.

On December 14, 2022, a new nationwide strike took place in Jordan four years after another strike toppled the government of Prime Minister Hani Mulki. Again, the motives are economic. Led by truck drivers, the new protests in Jordan are over the increase in gasoline prices following the government’s disclosure of its planned budget for 2023. Since the strikes began, the protesters enjoyed a significant level of support among Jordanians, who are already suffering from the current economic situation, especially with the rise of unemployment and poverty rates.

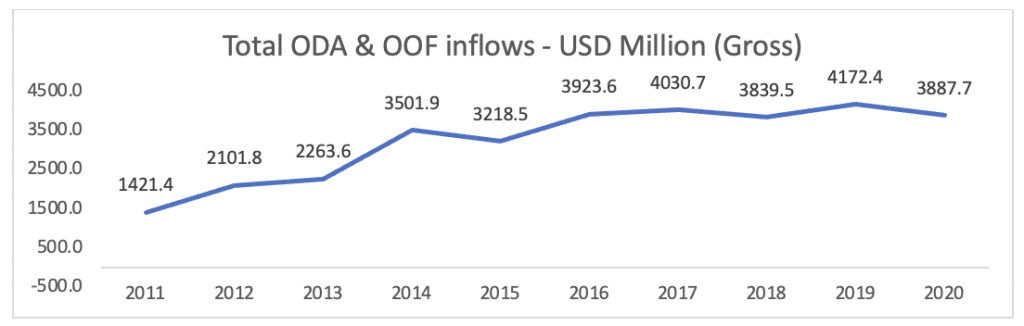

The protests led to clashes with police and the killing of a police officer on December 16, 2022. The situation in Jordan raises many questions on why Amman is still unable to reform its economy despite receiving tremendous amounts of foreign aid—around $3.5 billion annually. It also raises many questions on why the Jordanian government seeks easy solutions, like gasoline price increases, instead of implementing structural reforms to solve Jordan’s fiscal and economic issues.

In the Jordanian context, international and local analysts blame this situation on limited resources, limited fiscal capacity, and regional turmoil. However, these are only symptoms of Jordanian economic structural weaknesses.

Top aid recipient but slow on reform

Jordan is highly aid dependent and among the top US and international foreign aid recipients globally. Despite that, foreign aid was one of Jordan’s main stabilizing factors in the past few years. Yet, many questions are being raised among Jordanians and international observers regarding slow reform implementation in the country and the persistently weak economy. In fact, Jordan is one of the top foreign aid recipients globally. For example, Jordan was the second highest aid-receiving country from the United States in 2021. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data, Jordan received around $32.4 billion during 2011-2020 in foreign aid, as shown in the graph below.

Notwithstanding the tremendous amounts of foreign aid received by Jordan, the country is currently suffering from a 22.6 percent overall unemployment rate, a public debt constituting around 110 percent of the country’s GDP, and around 27 percent of the population living in poverty. Moreover, polling data shows a significant level of dissatisfaction among Jordanians, where 70 percent believe that their country is “governed in the interest of a few.” However, as this article argues, that is not the only issue, with there being five main obstacles to economic reform implementation in Jordan.

Lack of government autonomy

Civilian government autonomy vis-à-vis other forces within a political system is a defining factor of a government’s ability to implement reform. In the Jordanian context, the government faces several forces that undermine its ability to control state institutions and take ownership of reform implementation. For example, the monarch of Jordan enjoys extensive constitutional powers leaving limited room for his civilian government’s control and lead of state institutions.

During 2016 and 2022, the Jordanian constitution was amended to expand the monarch’s powers to the judiciary, foreign policy, defense, and security, alongside his powers of hiring and firing the ministerial cabinet, hiring the house of senate, and dissolving the parliament. The constitution now grants the king the powers of appointing and dismissing the chief justice, head of the sharia judicial council, grand mufti, chief of the royal court, minister of the court, and court advisors.

This expansion of the king’s powers has been associated with an increased turnover of ministerial cabinets. From 1999 until the present, Jordan has had thirteen prime ministers, nineteen different governments, and forty-two cabinet reshuffles. This led to short-aged governments with an average life span of 1.2 years. The high turnover made Jordanian ministerial cabinets hesitant to take unpopular measures that might contradict the royal court vision—lest they be dissolved by the king.

Similarly, due to the weak economy, Jordanian governments have limited space to implement crucial reforms that spawn controversy and public dissent. The accumulated public grievances, weak economic situation, and the huge penetration of social media made it easier for Jordanians to gather and express their anger against government policies. Consequently, this has led to governments delaying reforms or diverting policies.

Jordanians do not trust their political system

A recent 2022 national survey published by the International Republican Institute in Jordan shows that almost 40 percent of Jordanians believe the country is mostly headed in the wrong direction, a 24 percent increase from 2020. Similarly, public trust levels in the government—particularly the ministerial cabinet—have declined significantly after the 2011 Arab Spring. The Arab Barometer data shows that the proportion of Jordanians who trust the government declined from 71.5 percent in 2011 to 43.3 percent in 2020. The same applies to parliament, where trust levels declined from 48 percent in 2011 to 13.7 percent in 2018. This decline in social trust in state institutions reduced the credibility of current reform programs and created more space for populist forces to build influence that hinders reform.

Poor elite recruitment mechanisms

With the persistence of “institutional favoritism,” Jordan lacks clear, transparent, and effective elite recruitment mechanisms. Public offices are obtained via favoritism, nepotism, and clientelism. In other words, “elite recruitment continues to be based on personal friendship, if not family relationship,” according to academics Oliver Schlumberger and André Bank.

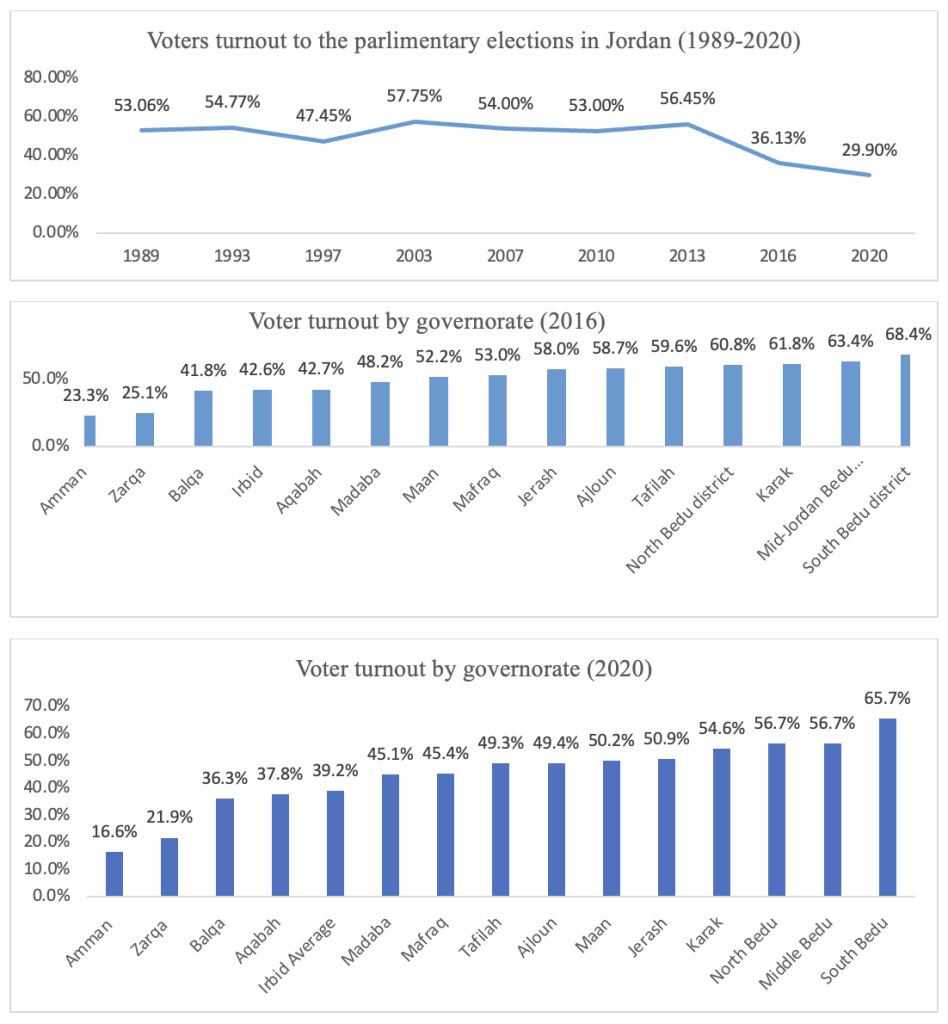

When it comes to elected officials, Jordanian parliaments face many legitimacy questions due to unfair representation of the public. For instance, voter turnout in the latest elections of 2020 reached only 29.9 percent, with many questions raised on election fairness due to COVID-19 measures back then. Moreover, voting behavior in Jordan is predominantly tribal.

In the 2016 and 2020 parliamentary elections, the majority of voting came from tribal districts, while the urban cities of Amman and Zarqa witnessed the lowest voter turnout in both elections (in the 2020 elections, eligible voters in Amman and Zarqa constituted 53.54 percent of the national electorate). On the other side, the highest turnout rates in both elections came from the three Bedouin districts of Jordan, in addition to other cities with tribal majorities, as shown in the graphs below.

Private sector marginalization

Despite Jordan’s active involvement in liberalization programs with the World Bank and International Monetary Fund since 1989, the Jordanian private sector still struggles with governmental control over the economy. In fact, investor confidence levels have been declining over the past few years. The Investor Confidence Survey published by the Jordan Strategy Forum shows that the percentage of investors who see the business environment being “not encouraging” for investment increased from 56 percent in 2017 to 68.4 percent in 2022.

Moreover, the Jordanian private sector is highly state-dependent, making it less able to grow autonomously. For example, financial facilities—such as loans and government bonds—provided by the Jordanian banking sector to the Government of Jordan constituted around 22.7 percent of the sector assets during the period 2010-2020, making the sector highly dependent on the state and less able to provide financing for the private sector. Similarly, the Jordanian government is currently doing business through the military. According to the Jordanian ministry of trade and industry data, seventeen new companies were registered during 2006-2022 with the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) as a partner. Eleven of these companies were registered between 2019 and 2022. These businesses owned by the Jordanian military work in military equipment development, agriculture, mining, construction, real estate, and telecommunications. Therefore, the government of Jordan is crowding the private sector instead of creating a growth-enabling environment for private enterprises.

Declining human capital

The high unemployment rate in Jordan (22.6 percent) is caused by many structural distortions in the labor market. One of these main problems is declining human capital. Jordan’s score of 55/100 in the World Bank’s 2022 human capital index is “lower than the average for the Middle East [and] North Africa region.” This implies that “a child born in Jordan just before the pandemic will be 55 percent as productive when she grows up as she could be if she enjoyed complete education and full health.” Additionally, Jordanian school students scored below the global average on the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test. In other words, Jordan cannot fill the private and public sectors with talented and innovative workers.

Based on the aforementioned issues, Jordan’s economic struggles cannot be reduced to the regional situation and weak fiscal capacity. Many other structural issues need to be tackled by serious economic and administrative reforms that require leadership and political will. The current reform plans neglect the fundamentals and propose superficial economic reforms.

Politically, the current plans try to build an ineffective democratic façade. Without tackling the root causes of the country’s issues, such as corruption, weak education, favoritism, political tribalism, and lack of leadership, the country will only delay the crisis and it will snowball into something larger in the future. Therefore, Jordan is expected to witness more protests and public dissent if structural reforms are not implemented.

Laith Alajlouni is a Jordanian political economist. He worked as a policy consultant for different organizations including the World Bank. Follow him on Twitter: @LaithAlajlouni.

Further reading

Mon, Dec 14, 2020

Is Jordan’s workforce ready for emerging opportunities in digital entrepreneurship?

MENASource By Nicole Goldin

By tapping into its large, tech-savvy youth population, which makes up more than half of its citizens, and its markedly underutilized female labor force, Jordan can position itself for dynamic post-COVID economic expansion.

Mon, Apr 5, 2021

Experts React: A royal rift in Jordan amid competing allegations of a coup & corruption

MENASource By

Atlantic Council experts react to the latest news of the royal rift in Jordan and how recent events may impact the country’s security, economy, and regional standing.

Fri, Apr 9, 2021

Jordan was never ‘boring.’ A vibrant protest movement has been ignored for too long.

MENASource By Tuqa Nusairat

The greatest risk to Jordan’s stability remains that political and economic reform has been delayed for too long, and the little space that remains for Jordanians to express their legitimate frustration and dissent is narrowing every day.

Image: A cyclist passes in front of the image of Abdullah II of Jordan, inside the Amman Citadel historical site. On Wednesday, January 30, 2019, in Amman, Jordan. (Photo by Artur Widak/NurPhoto)