Where Syria goes next after the fall of Assad

The departure of Bashar al-Assad from Syria and the implosion of his regime is, for me, easily the most pleasant geopolitical surprise of the twenty-first century. Twenty million Syrians face continued tough times as men with weapons try to sort out what is next in terms of governance. But there is but one absolute certainty: With Assad gone, Syrians now have a chance to live lives of decency, dignity, and opportunity.

It seems like ages ago when I sat with President Assad on February 28, 2011, in a palace high above Damascus, informing him of what specifically would be required of Syria to recover all land—mainly the Golan Heights—lost to Israel in 1967. That fifty-minute conversation and subsequent much longer talks with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and others would be the high points of a backchannel peace mediation that had gathered momentum in the fall of 2010. A White House colleague and I were so encouraged by our progress that we planned to bring Syrian and Israeli officials together in an Eastern European capital in April 2011. But it never happened.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

The prospect of Syria-Israel peace died in mid-March 2011 when Assad ordered his security apparatus to use deadly force against Syrians peacefully protesting police violence and the mass, illegal detention of pro-democracy advocates. By shooting demonstrators and filling prisons, Assad did much more than effectively cede the Golan Heights to Israel. He destroyed what was left in Syria in the hope that a well-educated young president might reform the brutally authoritarian system he inherited from his father, Hafez. And as Assad doubled and tripled down on violence for much of 2011, he set the stage for internal warfare that would all but destroy the country and, on December 8, send him packing.

So how did it happen?

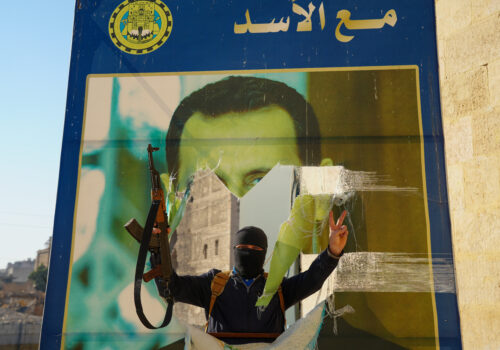

Syrian rebels, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), seem to have decided last month to take advantage of the recent defeats suffered by Iran and Lebanese Hezbollah by trying to expand their rule in northwestern Syria to Aleppo. They did so almost effortlessly. Indeed, as they entered Aleppo and pushed beyond, they found regime military forces dissolving in front of them. A Syrian army degraded by inactivity and hollowed out by criminality, corruption, and amphetamine production—Captagon—was simply in no condition to fight. The door to Hama, Homs, and Damascus was wide open, and HTS, led by Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, did not hesitate to enter.

The Assad regime’s greatest supporters—Iran and Russia—were at first strongly inclined to prop up their client, as they have done for a dozen years. For Iran, Syria is the land bridge to what is left of Hezbollah in Lebanon, and Hezbollah has—at least until recently—been the jewel in the crown of foreign policy accomplishments by Iran’s clerics. For Russian President Vladimir Putin, Syria was much more than a country offering naval and air facilities. Rescuing Assad in the past was Putin’s top domestic political talking point about the supposed return of Russia to great power status. Tehran and Moscow wanted desperately to shore up the regime. But they could find nothing to support. All they found, in the words of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias, was “boundless and bare. The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

No one, except perhaps Assad himself, knew that the regime over which he had presided for nearly a quarter century, one built by his father, was, in fact, a “colossal wreck,” in the words of Shelley. That the regime had fragmented into criminal cliques, with the Assad family and entourage looting what they could from the country they had wrecked, was widely known. Still, it was widely assumed by many, including me, that the regime’s appetites for mass homicide, torture, rape, starvation, terror, and theft remained strong, and the means required to convert appetites to actions remained intact. In the end, however, the acidic evil of a crime family and its enablers dissolved everything.

What, then, is next? Jolani, the head of HTS, appears to be the big winner, although it is far from clear in the opening hours of the post-Assad era exactly what he commands. While Jolani claims to have severed his connection to al-Qaeda in 2016, HTS remains a Turkish– and US-designated terror organization.

The Joe Biden administration seems pleased that the mass-murdering client of Iran and Russia has fled. Yet Washington’s ambivalence concerning HTS is understandable. On the one hand, HTS is deeply committed to liquidating the presence and influence in Syria of the Iran-Hezbollah combination and perhaps that of Russia as well. On the other hand, however, its Islamist orientation poses potential dangers to Syrian minorities—especially Alawites and Christians—as well as the prospect of Syrian governance falling into the hands of a fundamentalist group containing foreign fighters and perhaps even still harboring global terrorist sentiments.

These well-founded reservations about HTS mandate close coordination and cooperation between Washington and Ankara, notwithstanding severe bilateral differences over the US military relationship with the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Defense Forces in northeastern Syria.

Indeed, Turkey sees no advantage in Syria being “governed” by anyone whose blatant sectarianism is likely to send refugees surging in its direction. Turkey has already had this experience thanks to Assad’s campaign of mass homicide directed at Syrian Sunni Muslims in rebel areas. Indeed, Ankara’s support for the current rebel offensive probably has its roots in Assad’s failure to provide guarantees for the safe and protected return of Syrian refugees from Turkey, a major domestic political priority of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. One hopes Ankara can exert some influence over what comes next.

Jolani is publicly speaking about his dedication to minority rights, governing through institutions, and rebuilding Syria after thirteen years of internal warfare. This is all to the good if it indicates his conversion from al-Qaeda is complete and if he is truly interested in promoting the kind of Syria of which he speaks. Yet, HTS’ human rights record in Syria’s northwest has been abysmal. Perhaps Turkey, with input from Washington, can persuade Jolani to take the following steps now that Assad is finished:

- Offer to form a national unity, transitional government with the current Baathist Syrian Arab Republic Government, headed by Prime Minister Mohammed Ghazi al-Jalali. Priorities of such a government would include establishing law and order with justice for all, releasing all political prisoners, ensuring the departure of foreign forces from Syrian territory, providing for the safe return of Syrian refugees, securing the lifting of sanctions and initiating reconstruction, and setting the conditions for eventual parliamentary elections and even constitutional reform.

- Pledge that HTS armed forces will not enter Latakia province or any other places where Alawite Syrians reside. Syrian authorities could, if necessary, ask for Turkish assistance if help is needed, defending civilians from anyone motivated by feelings of vengeance.

- Identify, in conjunction with other Syrian opposition elements, senior professional Syrian military officers who have defected over the years and place them in command of what remains of the Syrian armed forces. To the maximum extent possible, use existing Syrian Army units under new, decent, and professional leadership to provide security in populated areas. Permit HTS personnel to join the Syrian military and set a deadline of six months to do so or disarm.

- Clarify to the people of Syria that the rule of law in the post-Assad era would convey neither advantage nor disadvantage to any Syrian based on sect. Begin work on a new, inclusive Syrian Constitution.

The United States should move quickly, as soon as security conditions permit, to dispatch a special envoy to Syria and to reopen the US Embassy in Damascus. Direct contact with Jolani is essential; granting him the benefit of the doubt up-front would preserve the possibility of influencing him. Sanctions on the Assad family and entourage should be maintained, and Assad’s transport to The Hague to be prosecuted for crimes against humanity should be pressed upon whoever ends up hosting him. All other economic sanctions on Syria should be suspended. The US should provide humanitarian assistance and organize a structure to advance Syria’s reconstruction in conjunction with allies and partners. There are reports that the regime kingpins emptied Syria’s Central Bank on the way to the Damascus airport. If true, the US should assist Syria’s new government in recovering stolen assets.

Although Turkey may be the most important American interlocutor in the coming days and weeks, Washington should spare no effort to create a united front toward Syria among allies and partners. France will be important in this regard, as will the United Arab Emirates (UAE). According to press reports, Abu Dhabi, before the rebel offensive, attempted to ensnare Washington in a foolhardy scheme to lift US sanctions in return for Assad’s promise to halt arms flows to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Now the UAE is wringing its hands over Assad’s departure, warning—perhaps because of Abu Dhabi’s antipathy toward Turkey—that something akin to Libya or Afghanistan is very much in Syria’s future—as if Libyans and Afghans have suffered anything close to what Syrians have suffered for decades under the Assads.

Undoubtedly, twenty million Syrians now face a future with many challenges and more than a few errors. Yet the “devil they knew” surely was the devil. With the Assad family and entourage gone, Syria, at long last, has a chance to achieve the kind of political transition envisioned by the 2012 Geneva Final Communique and United Nations Security Council Resolution 2254. They will now have an opportunity, where none previously existed, to live, work, and thrive in their country of birth instead of seeking refuge and opportunity abroad. After years of persecution by a brutal regime, imperial abuse at the hands of Iran and Russia, and betrayal by regional and international actors, Syrians have taken their liberation into their own hands. They merit the United States’ help and its willingness to listen. But the Syrian revolution, regardless of what happens next, is where it belongs: In the hands of the Syrian people.

Frederic C. Hof is a senior fellow at Bard College’s Center for Civic Engagement. He is the author of Reaching for the Heights: The Inside Story of a Secret Attempt to Reach a Syrian-Israeli Peace.

Further reading

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Wed, Nov 27, 2024

War, peace, or a perpetual state of crisis—three possible paths for the Middle East’s future

MENASource By

The ongoing debate between escalation and de-escalation reveals the complexity of the region’s geopolitics and the different perspectives on future conflicts.

Thu, Feb 10, 2022

A perpetrator of Syrian crimes against humanity went free in France. Here’s why it shouldn’t happen again

MENASource By Michel Duclos

If the scope for changing the course of events in Syria is limited, it’s honorable to take a stand against the abominable crimes of the Bashar al-Assad regime. It would be a great pity for France to be seen as a safe haven for Assad’s accomplices.

Image: A view of personal souvenirs for Syria's Bashar al-Assad at one of the rooms at Presidential Palace known as Qasr al-Shaab "People's Palace", after rebels seized the capital and ousted Syria's Bashar al-Assad, in Damascus, Syria December 10, 2024. REUTERS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh