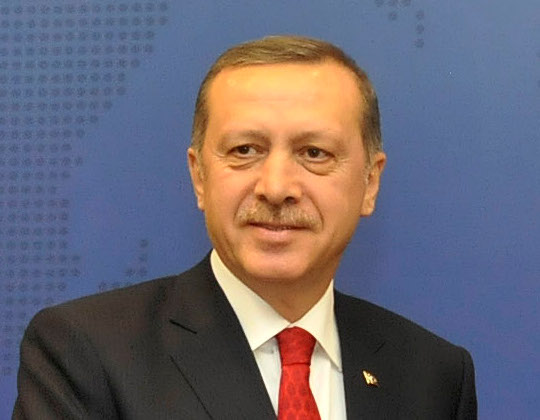

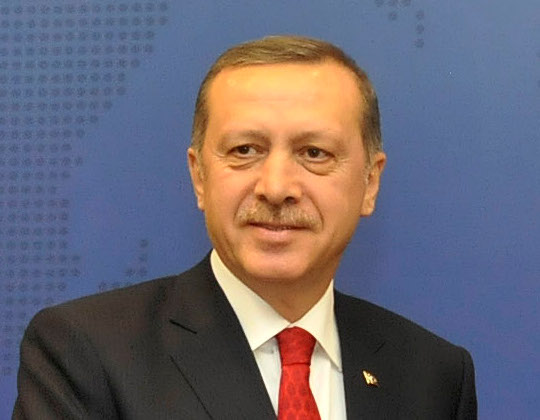

On 26 September, Turkey’s Undersecretariat for Defence Industries, presided over by the country’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, resolved a tender for the delivery of long-range air defence systems. The winner was China’s CPMIEC , the manufacturer of the FD-2000 system, which is a more advanced copy of the Russian-made S-300. Ankara has announced that it would start negotiations with CPMIEC. . . .

On 26 September, Turkey’s Undersecretariat for Defence Industries, presided over by the country’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, resolved a tender for the delivery of long-range air defence systems. The winner was China’s CPMIEC , the manufacturer of the FD-2000 system, which is a more advanced copy of the Russian-made S-300. Ankara has announced that it would start negotiations with CPMIEC. . . .

The decision to award the contract to CPMIEC is not yet final. It is possible that Ankara is only trying to pressure the Western defence companies into making more attractive proposals. If, however, it ultimately decides to buy the Chinese system, this will be a serious blow to the political and operational cohesion of NATO. The decision will also damage Ankara’s relations with Washington and undermine Turkey’s position in NATO. . . .

Should Turkey eventually conclude a deal with the Chinese company, this would seriously harm its relations with the United States. It would undermine Ankara’s position within NATO and the Alliance’s political cohesion and operational capabilities. The US has imposed sanctions on CPMIEC on several occasions in recent years for violating the embargo on defence technology supplies to Iran, North Korea and Syria (most recently in February 2013). Moreover, for the last several months the US has been sending clear signals that it was opposed to the conclusion of the Turkish-Chinese deal. According to unofficial reports, Washington’s reaction to Ankara’s decision was even worse than in 2011 when Turkey announced plans to purchase the Russian S-300 system (Washington ultimately managed to prevent those plans from becoming reality). NATO members have also issued repeated warnings that a non-NATO air defence system would not be compatible with the Alliance’s early warning systems. It is therefore likely that the United States and the other NATO members will try to persuade Ankara to change its decision. One of the ways to exert pressure on Turkey could be to withdraw the NATO Patriot system from the Turkish-Syrian border, which the Alliance deployed there at the request of Turkey in early 2012 to provide protection against a possible attack from Syria. . . .

At this stage it is difficult to determine if Turkey actually intends to award the contract to the Chinese company, or treats opening talks with CPMIEC merely as an element of its bargaining tactics in the negotiations with Western companies. Reconciling its ambitions to develop its own air defence capabilities with commitments stemming from NATO membership will remain an important and difficult challenge for Turkey. The country can achieve full air defence compatibility with the Alliance only by purchasing arms from other NATO members, in which case, however, it will not enjoy full independence and freedom to maintain and use the systems. Entering co-operation arrangements with Western companies would be an optimum solution for Turkey, but such co-operation would have to offer attractive price conditions and include technology transfers to the Turkish arms industry. It remains an open question if the US and French-Italian contractors will be willing to revise their proposals and offer Turkey better conditions. If Ankara ultimately decides to build its systems in co-operation with China, this will trigger a crisis in its relations with the other NATO members, and especially the United States.

Image: Turkey's decision to buy Chinese missiles is not yet final (photo: Government of Chile)