The Russian Foreign Ministry has continually insisted on legally binding guarantees that US missile defenses are not aimed at it and that would allow Russia access to sensitive aspects of the system. Russia has also threatened to deploy a range of countermeasures against NATO’s missile defenses, including tactical nuclear missile deployment in Kaliningrad and improvements to its strategic nuclear missile arsenal to make it capable of evading missile defense. Whether EPAA is aimed at Russia or technically capable of even potentially intercepting Russian missiles, however, are very different considerations. But the Russians seem to ignore that simple truth that the technology is limited by physics and engineering, not political considerations.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has continually insisted on legally binding guarantees that US missile defenses are not aimed at it and that would allow Russia access to sensitive aspects of the system. Russia has also threatened to deploy a range of countermeasures against NATO’s missile defenses, including tactical nuclear missile deployment in Kaliningrad and improvements to its strategic nuclear missile arsenal to make it capable of evading missile defense. Whether EPAA is aimed at Russia or technically capable of even potentially intercepting Russian missiles, however, are very different considerations. But the Russians seem to ignore that simple truth that the technology is limited by physics and engineering, not political considerations.

Ironically, moving the technology further away from Russian borders could increase the potential for its successful use against Russian missiles. So, whether or not Russian technical concerns could ever really be assuaged must be questioned.

Frank Rose, deputy assistant secretary of State for arms control, verification and compliance, restated in May 2013 the declaration made at the Chicago NATO Summit held in May 2012. “The NATO missile defense in Europe will not undermine strategic stability. NATO missile defense is not directed against Russia and will not undermine Russia’s strategic deterrence capabilities.” He went on to state that “through transparency and cooperation with the United States and NATO, Russia would see firsthand that this system is designed for ballistic missile threats from outside the Euro-Atlantic area, and that NATO missile defense systems can neither negate nor undermine Russia’s strategic deterrent capabilities. . . .”

A recent report by the U.S. General Accounting Office states that, to be more effective against Iranian ICBMs, interceptors should be based on ships in the North Sea (between the Netherlands, the UK and Scandinavia) rather than in Poland. This would buy valuable time against Iranian missiles but it is not without consequences for intercepting Russian ICBMs. . . .

Now, an interceptor launched at 300 s after the launch of the ICBM can reach it at 300 s into flight. Placing interceptors further away from Russia actually makes intercepting (some) Russian ICBMs easier. Russian protests would likely then follow missile defense placement there as well. However, if an early launch were possible somehow or interceptors were indeed to be based in the North Sea, Russia could still prevent its ICBMs from being intercepted by allocating ICBMs based in Western Russia to targets in the Western United States instead of near the East Coast and vice versa.

The Russians have certainly run such simulations and are aware of the technical limitations of EPAA as currently configured. Whether missile defense in Europe is the right answer to the question of dealing with missile threats from countries like Iran and North Korea aside, Russian protests ring hollow and their demands for assurance are reminiscent of that wonderful Charles Schultz cartoon series where Lucy kept moving the football away from Charlie Brown whenever he tried to kick it. Whatever assurances we give the Russians will probably not be enough. Simply put, Russia is just playing politics.

Joan Johnson-Freese, a member of the Breaking Defense Board of Contributors, is an expert on strategy, US military space and the Chinese military. She is a professor at the Naval War College and a lecturer at Harvard University. Ralph Savelsberg is an assistant professor at the Netherlands Defence Academy in Den Helder, specializing in missile defense.

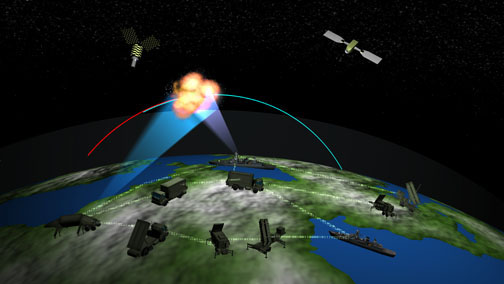

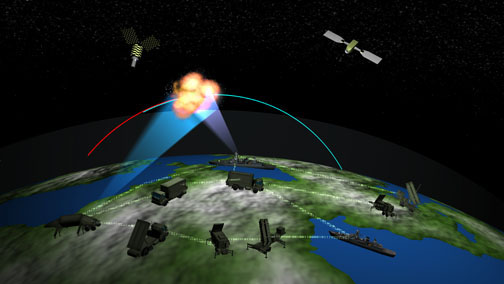

Image: NATO Missile Defense (graphic: NATO)