Despite Georgia’s readiness to become a candidate for NATO, the Alliance announced in late June that Georgia will not be offered a Membership Action Plan (MAP) at the Wales Summit this September. This is disappointing news for Georgia, which has undertaken years of political and military reforms and has long awaited to be welcomed into the Alliance. Although the United States was not able to persuade some of its fellow allies on MAP, US leadership must not only continue to press on the issue but also devote equally sustained attention to other elements of Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration. Russian recent aggression in Ukraine makes it all the more pressing for the United States to send a strong message that Georgia, and the region as a whole, is important by concluding a US-Georgia Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

Despite Georgia’s readiness to become a candidate for NATO, the Alliance announced in late June that Georgia will not be offered a Membership Action Plan (MAP) at the Wales Summit this September. This is disappointing news for Georgia, which has undertaken years of political and military reforms and has long awaited to be welcomed into the Alliance. Although the United States was not able to persuade some of its fellow allies on MAP, US leadership must not only continue to press on the issue but also devote equally sustained attention to other elements of Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic integration. Russian recent aggression in Ukraine makes it all the more pressing for the United States to send a strong message that Georgia, and the region as a whole, is important by concluding a US-Georgia Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

The United States and Georgia first outlined the mutual benefits of an FTA in a 2009 partnership charter. But FTA negotiations launched in earnest only in January 2012, after the United States worked to convince Georgia not to veto Russia’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since then FTA talks have not moved forward meaningfully, even as Tbilisi has improved its governance and business environment, enacted regulatory reforms, and met the demanding standards for the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) with the European Union (EU).

A US-Georgia free trade agreement is a win for both countries. It will help drive the needed economic and governance reforms in Tbilisi, send a strong signal to the Kremlin about US commitment to the region, and keep Washington’s economic footprint in an area of the world that is a strategic energy corridor and burgeoning transit hub.

Signaling US Commitment to Georgia

One significant, short-term benefit of an FTA would be the political message that Tbilisi remains Washington’s important partner and Georgia and its concerns have not fallen off the Obama administration’s regional agenda.

Georgia is a vibrant, yet imperfect, burgeoning democracy and a steadfast ally whose troops have fought alongside American forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. Georgia’s economic progress and its location at the crossroads of Europe, Russia, the Middle East, and Central Asia mean than it has the potential to transform into a regional economic and trade hub. In the past decade, the country has seen double-digit economic growth and World Bank estimates predict 5-6 percent (hyperlink: http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects/data) growth in the next couple of years.

Unleashing the Potential of US-Georgia Trade

Georgia’s newest trade agreement with the EU, while potentially painful in the short term, is predicted to increase exports to the EU by 12 percent and could increase Georgia’s long-term GDP by more than 4 percent with full implementation of trade-related reforms. A US-Georgia FTA would build on these successes and add to Georgia’s economic growth.

Generally US trade agreements are complicated and take a long time to execute, but the US-Georgia FTA could be done quickly. The countries have had a bilateral investment treaty since 1997, are both members of the WTO, have a relatively low volume of trade, and have economic structures open to international trade and investment. The United States (along with the EU, Japan, Canada, Switzerland, and Norway) has already granted Georgia a Generalized System of Preference (GSP), which gives low or zero-rated tariffs to Georgian products. The FTA could also be done cheaply. The United States would lose a minuscule amount of customs revenue (in 2010 the United States received just $226,000 from Georgia) on tariff imports. Unfortunately, Georgia’s DCFTA with the EU might delay some aspects of an FTA because of the differences in US and European regulations on genetically modified organism (GMO) products, hormone-treated beef, and other technical barriers. If the trade regimes are not synergized, Tbilisi will be forced to apply EU mandated restrictions on imports from the United States. The United States and EU conflicting regulatory schemes can be solved under the scope of the much heralded EU-US trade agreement.

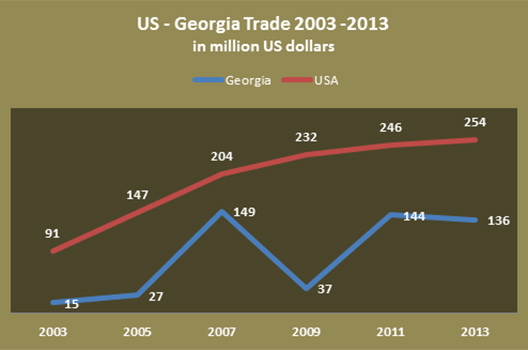

Source: National Statistics Office of Georgia.

Under the GSP, Georgia’s exports to the United States have increased by almost 700 percent. Over the past decade, imports from the US went up by almost 180 percent as well and constituted 254 million US dollars in 2013. The United States is the ninth-largest source of imports for Georgia, while being the fourth-largest export destination for Georgia’s walnuts; dried, processed and fresh fruits and vegetables; wine; ferroalloys; ceramic and glass articles; and handicraft textiles.

Investing in Georgia’s Long-Term Development

It is too early to assess the specific costs and benefits of a future trade agreement, since it is not yet clear whether the agreement will be limited to agriculture and manufactured products or expanded to include services and e-commerce. Nonetheless, there are a number of indirect benefits for Georgia’s development.

An FTA with the United States would be a strong incentive for foreign investors to move or open production centers in Georgia, since only products manufactured in country will be eligible for a low or no tariff regime. Throughout the past decade Georgia has proactively liberalized its economy and opened it to attract foreign investment, entrepreneurs, brainpower, and technological innovators. Tbilisi’s current administration too is actively campaigning to attract investments for the “one hundred new factories” promised in the past elections. An FTA could ease this task and spur job-creation. Official estimates put the unemployment rate at 14.5 percent, making it one of the main economic challenges.

Providing assistance (and incentives) to continue institutional reforms and technology transfer is another benefit of FTAs. Although Georgia undergone significant modernizing of its internal governance, there is large space for improvement, particularly in the areas of intellectual property protection, competition policies, trade-related institution-building, and sanitary standards and product origin certification. Georgia will be able to specify the areas it would like to have training and technology transfer in, probably wine production, food processing, and IT technology, further improving and modernizing its goods and services to make them competitive.

Georgia is a stalwart ally with a growing economy and increasing regional trade and transport role in a region of the world that is moving away from democracy and free markets and increasingly bullied by Moscow. While devoting time and resources to the crisis in Ukraine, United States should continue assisting other reformers by investing in the long-term stability and development in the region. A United States-Georgia Free Trade Agreement is the type of investment that will benefit both parties and steps should be immediately taken to move from talk to action.

Nino Ghvinadze is a researcher at the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). Laura Linderman is a research fellow with the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center at the Atlantic Council.

The opinions expressed in the article do not necessarily represent the position of the ICMPD or the Atlantic Council.