Abolishing FEMA would hurt all Americans—particularly Trump voters

On January 24, while traveling between hurricane cleanup in North Carolina and fire recovery in California, US President Donald Trump announced that he would sign an executive order to study abolishing the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The agency’s main mission is to provide disaster recovery grants and other assistance vital to states, cities, and individuals recovering from hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and other natural and man-made disasters. A potential alternative, Trump said, was leaving disaster recovery up to the states, with the federal government giving states money but nothing else after a disaster occurs.

Eliminating FEMA would be a disaster, as it would surely lead to greater suffering and higher costs after disasters. In a cruel irony, moreover, abolishing FEMA would likely hurt the worst in states that supported Trump, especially Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and the Carolinas. These states went for Trump in the 2024 election and will be important politically in the 2026 midterms.

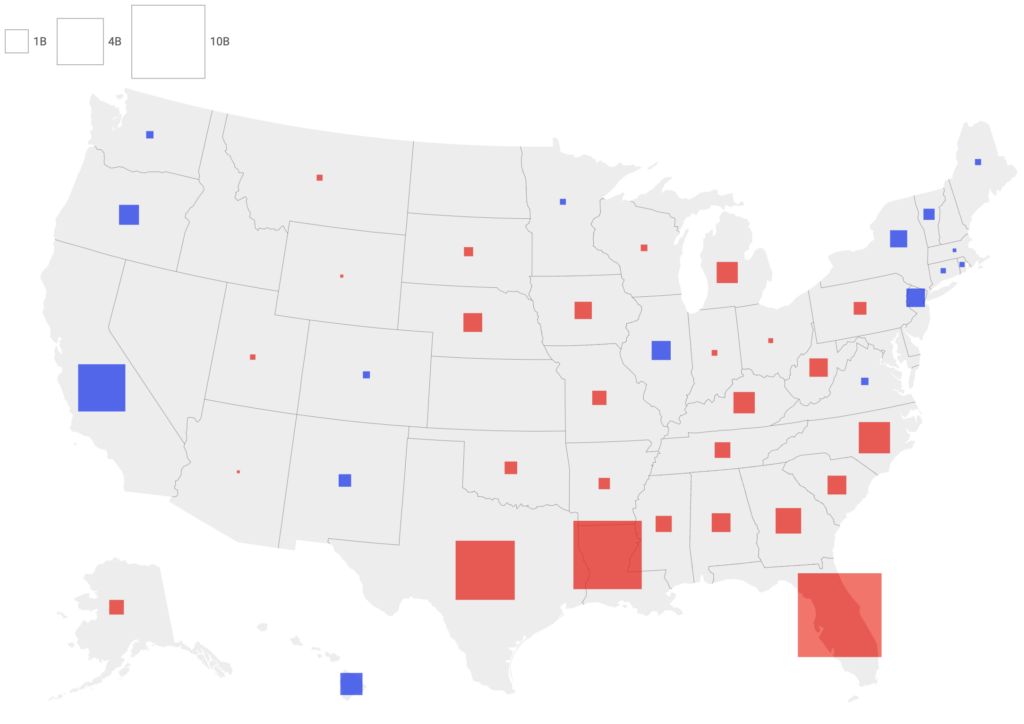

Most recent FEMA funds have gone to states that went for Trump in 2024

Size reflects total FEMA disaster grants Oct. 1, 2015 through Jan. 8, 2025; colors reflect the 2024 presidential election results.

Instead of abolishing FEMA, which is part of the Department of Homeland Security and includes other missions besides disaster recovery, Trump should seek to fix the agency’s problems, make it more efficient, and change its focus to include strategic resilience—that is, saving lives and reducing property damage before disasters strike.

While FEMA does serve to get disaster relief money to the states, it does five important things that states need after a disaster and that virtually every state—but especially some red states—would have to budget for, at considerable ongoing expense, if FEMA no longer existed. Emergency management requires training and experience—it is no longer a game for amateurs.

First, FEMA has specialized experience in disaster response and recovery. It deploys hundreds of experts to states where disasters occur. If FEMA were abolished, states would have to hire and train their own experts at considerable cost to state budgets—or do without.

Second, FEMA maintains stockpiles of essential commodities needed in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, which states would have to replicate or do without after a disaster.

Third, when the response to a disaster moves into the recovery phase, FEMA has special expertise in rebuilding infrastructure—expertise that states would have to replace.

Fourth, FEMA is better able than individual states to pull in expertise from other parts of the federal government to restore water treatment facilities, rebuild schools, and do the other necessary recovery work when a community gets devastated.

Fifth, at all phases of response and recovery, FEMA has the capacity to administer individual grants and account for them afterward—specialized expertise that states would have to replicate on their own if FEMA did not exist.

Additionally, and precisely because of its knowledge in response and recovery, FEMA also has more accumulated experience in how to prevent damage from disasters, and how to reduce the cost and time of recovery when disasters do occur. This expertise in resilience needs to be tapped to better save lives and reduce the cost of future disasters. This goes to the heart of what strategic resilience is all about.

Disasters can strike anywhere—but some places get hit worse

It is undeniable that disasters are getting more costly to communities. In the past six months alone, hurricanes Helene and Milton and wildfires in southern California have killed at least one hundred Americans and caused more than $100 billion in damage to homes and businesses. While hurricanes and wildfires vary in number and magnitude, they happen every year somewhere in the United States. Earthquakes and pandemics are less frequent, but whether tomorrow or years from now, they will happen. One lesson from the COVID-19 pandemic at the end of Trump’s first term is that better preparedness could have saved many more lives and helped keep the US economy going.

But the cost of disasters is not spread evenly across the country. As the map above shows, it is striking which states benefit from FEMA’s disaster grants. Of the $45.3 billion in FEMA disaster grants from October 1, 2015, through January 8, 2025 (this excludes grants to Puerto Rico and other territories), 82.8 percent went to states that Trump won in the 2024 election. The majority of FEMA disaster aid went to red states in the southeast, with the largest beneficiary being Trump’s home state of Florida, which received more than thirteen billion dollars.

Republicans who recently called for conditions on disaster assistance to California do so at their own political risk—and grave financial risk to the people they represent. In principle, disaster assistance is supposed to come fast and does not have policy conditions. In reality, it often depends on the US Congress passing a supplemental appropriation. Imposing conditions will likely have even worse consequences on Republican-led states such as Florida, Louisiana, Texas, and South Carolina, where Democrats in the future could seek payback by conditioning hurricane disaster relief on a range of policy changes from climate change to abortion policy. California may not have another wildfire season like the one this month for several years, but hurricane damage on the Gulf Coast or the southeast this or next year is a near-certainty. If Congress imposes conditions on disaster assistance, Republicans could have far more to lose in the future than Democrats.

Republicans are therefore right that there are a wealth of policy changes and investments needed in California. The same is true about Florida, Louisiana, Texas, the Carolinas, the Gulf Coast, and the Midwest. But conditioning disaster assistance on policy changes is bad for everyone. The need to approach these changes in a constructive, not confrontational, way should be one aspect of a Trump-commissioned study of what the United States needs from strategic resilience.

A bad deal for all states—red, blue, and purple

Trump’s suggestion to replace FEMA with a cash grant to states after a disaster misses the full extent of what FEMA does. The agency does give out grants to pay for rebuilding after widespread destruction from hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and tornadoes. While FEMA’s employees are not first responders—state and local governments are responsible for first response—the agency has thousands of people it can deploy who are experts in disaster response and recovery, rebuilding infrastructure, and grants management. FEMA also maintains stockpiles of emergency supplies and equipment, such as generators, and can marshal other parts of the federal government to do the essential but unglamorous work of rebuilding after a major disaster.

In contrast, when states were left to themselves during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the result was chaos. The governor of Maryland, for example, bought 500,000 test kits from South Korea and then used the Maryland National Guard to keep them away from the federal government. Under Trump’s approach, states would likely end up bidding for scarce expertise and emergency supplies. This, too, could end up hurting a high number of Trump’s supporters, since blue states on average have larger state budgets per capita than red states and have a higher gross domestic product per capita, too.

Democratic-leaning states could have an advantage in a potential bidding war for emergency supplies

As a result, red states may lose out in bidding wars to blue states under such an approach.

One important but unstated role FEMA plays is that it allows states (red and blue) to have smaller governments than those states would need if they had to prepare for emergencies on their own. Leaving disaster assistance up to the states would mean that each state would need to replace a lot of what FEMA does with its own personnel—or let its people suffer catastrophic losses after a disaster. Hiring a national cadre of emergency response professionals that can be deployed to states where disasters occur is far more cost-effective than every state having to hire and train its own people.

Three areas for reform

The professionals at FEMA and state-level emergency managers will be the first to tell you there are more efficient ways to save lives and reduce property damage. In March 2024, the Atlantic Council hosted one such event with these professionals, and it has been exploring this issue through the Adrienne Arsht National Security Resilience Initiative. Trump should invite in FEMA regional leaders and state emergency managers and listen to their ideas. Many of their ideas will likely center around three key themes:

1. Congress and state legislatures, not emergency managers, are the major reason there is so much bureaucracy and inefficiency in disaster response.

FEMA spent nearly half its disaster budget eight days into this fiscal year because of hurricanes Helene and Milton. This is in part because of how disaster response is funded. State legislatures, especially in red states, have habitually underfunded emergency response and recovery. Getting a check afterward from the federal government will not make up for a shortage of expertise in the hours, days, weeks, and months after a community is devastated by a hurricane, wildfire, or tornado.

2. There is a coming insurance crisis caused by ever-increasing damage from hurricanes, floods, and wildfires.

Already, insurance rates in Florida and other Gulf states have skyrocketed, and California’s already horrible insurance situation is about to become desperate. Homeowners must have insurance, or they cannot get a federally insured mortgage to buy a house. Businesses need to have insurance to be able to stay in business, and if they can’t stay in business and don’t have insurance, unemployment skyrockets.

Two Category 5 hurricanes hitting Florida or a Gulf state in a single season or another catastrophic California wildfire season next winter could put the economies of those states, and perhaps the country, into recession. Americans living elsewhere should not be smug: they will get hit by the bills if Congress has to appropriate hundreds of billions of dollars in emergency aid. The resulting economic catastrophe would cause a terrible human toll by ruining the lives of millions of Americans—many of them in red states.

3. There is a lot that can be done by focusing on strategic resilience to save lives and reduce property damage.

A 2018 study by the National Institute of Building Sciences found that every one dollar in disaster mitigation by FEMA and a program at the Department of Housing and Urban Development saved the US taxpayer six dollars in economic losses through such measures as rebuilding damaged houses on elevated foundations to reduce damage from future storm surges. In specific areas like river flooding, the payoff was even higher. While these estimates are now seven years old, and some initial investments were made during the Biden administration, federal and state emergency managers across the United States have some excellent ideas for cost-effective ways to reduce future losses. But this requires keeping FEMA, incorporating strategic resilience into its mission, and giving the agency the authority to work with states, local governments, and the private sector to do more to protect lives and reduce property damage.

As Trump’s administration looks more into this critical issue, Trump should invite federal, regional, and state emergency managers to Washington and figure out how to improve national disaster response. Trump should not make it worse by abolishing FEMA, which would cause disproportionate harm to many of the people who voted him into office.

Thomas S. Warrick is the director of the Future of DHS project at the Atlantic Council Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and a nonresident senior fellow with the Adrienne Arsht National Security Resilience Initiative. He previously served as deputy assistant secretary for counterterrorism policy at the US Department of Homeland Security.

Further reading

Tue, Jan 21, 2025

The US retreat on climate comes with steep costs for the economy and the American people

New Atlanticist By Jorge Gastelumendi

Trump's withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will not only hamper global efforts to combat climate change, but also harm Americans' lives and livelihoods.

Tue, Nov 19, 2024

Border security and the future of DHS: Will Trump 2.0 earn the public’s trust?

New Atlanticist By Thomas S. Warrick

The incoming US president has promised mass deportations, but there are three circumstances that could erode public support for the plans.

Thu, Sep 26, 2024

The Secret Service needs a budget increase—but so does the rest of the Department of Homeland Security

Future of DHS By Thomas S. Warrick

On Wednesday, Congress passed a bill to increase Secret Service funding in response to threats, after two assassination attempts against Donald Trump. The same logic should apply to the overall DHS budget.

Image: A resident enters a FEMA's improvised station to attend claims by local residents affected by floods following the passing of Hurricane Helene, in Marion, North Carolina, U.S., October 5, 2024. REUTERS/Eduardo Munoz