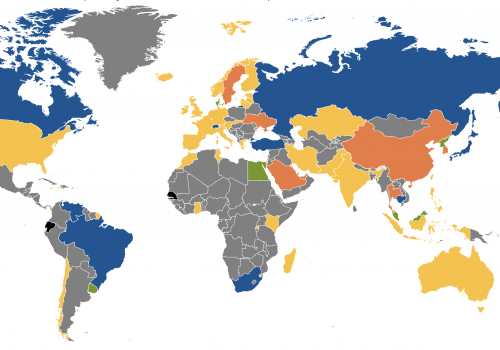

China’s rapid testing during 2020 of experimental central bank digital currency (CBDC) solutions demonstrates their clear commitment to deploying next-generation technologies to facilitate faster, easier payments that compete with, and eventually replace, cash. As noted in our companion post this week, China’s DCEP (digital currency electronic payment) initiatives raise a number of profound monetary policy and regulatory policy issues that go to the core of the global economy, as well as important privacy issues for open, democratic economies that favor checks and balances across government institutions and central bank independence.

Advanced economy central banks are also actively engaged in CBDC research and development efforts. But as guardians of global reserve currencies, their approaches will necessarily be more deliberate and cautious than Beijing’s aggressiveness.

China is not alone

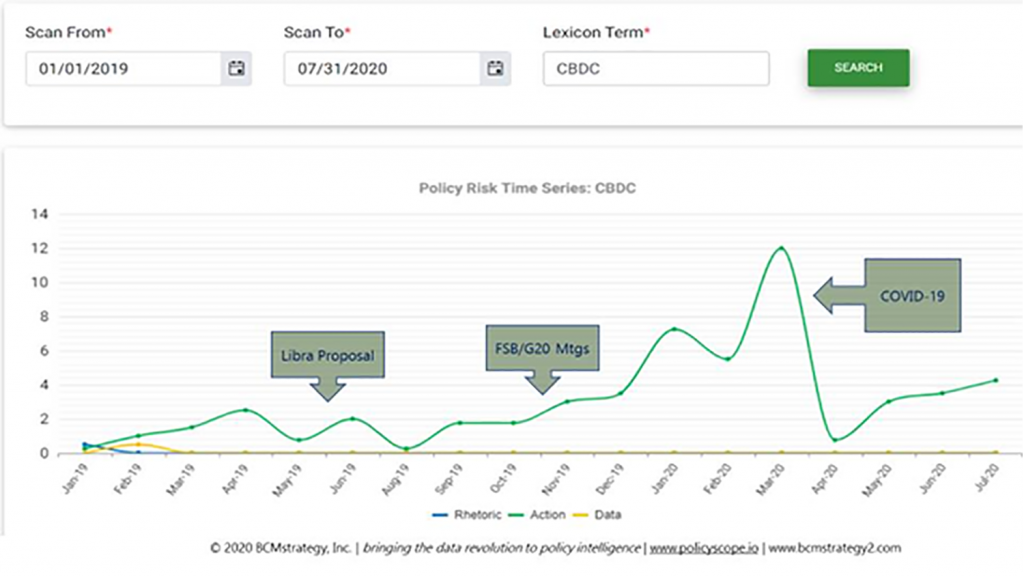

A deep, intense, thoughtful, and steadily accelerating policy debate has been underway in the global central banking community since early 2019. Activity accelerated in early 2020 with the creation of a cross-border working group representing five global reserve currencies (Canada, the European Union, Japan, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) plus Sweden.

The COVID-19 pandemic took its toll, as the data above indicates. However, activity levels have been increasing steadily throughout the summer among developed economy central banks.

During August alone, the US Federal Reserve has announced steps towards implementing instant payments in the United States in 2023 or 2024 as well as detailing its CBDC research efforts which include partnerships with MIT and the BIS Innovation Hub as well as a national research and experimentation program to design and build a “hypothetical digital currency oriented for central bank use.”

The Federal Reserve will not, however, spring a new digital dollar on the global economy without advance notice. Nor has the Federal Reserve concluded that it will issue a digital dollar…at least not yet.

Competition makes progress inevitable, caution makes it slow

Central banks and sovereign currency issuers are not immune from competition. In fact, inefficiencies within existing payments processes provide incentives for private parties to deliver alternative mechanisms that better address user needs. CBDC policy initiatives involve not only direct launch activities and competition with other sovereign currency issuers but indirect efforts to counter competition from privately issued stablecoins.

Need for speed: One major advantage associated with a range of alternative payment providers (peer-to-peer networks, payment cards, cryptocurrencies) is that value transfers occur instantly from the consumer’s perspective. The consumer does not need to wait for a check to clear or for a funds transfer to be credited to an account. The new generation of consumers will no longer tolerate days-long delays for payments to be processed. Nonbank technology companies now provide a ready alternative, potentially siphoning off avenues for monetary policy transmission and data collection needed to formulate monetary policy and financial stability analysis.

The European Central Bank appreciated the challenge faster than the United States. They launched an instant payments network in November 2018. The Federal Reserve is only acting with all deliberate speed. A slow and deliberate approach is only possible under the assumptions that no other credible, alternative stores of value will achieve consumer confidence and scale relative to the sovereign-issued currency during the same time period.

The Bank of England also appreciates the challenge. The early August financial stability statement from the Financial Policy Committee made clear that policymakers are looking over their shoulder and assessing carefully their competitors in the currency arena. Specifically, they made clear that private sector stablecoin issuers will be required to “offer the equivalent protections” currently available to bank deposits. The implication is that a private issuer—with fiduciary obligations to boards and investors—will not have the ability or capacity to serve as a source of strength comparable to that provided by official sector deposit insurers and/or lenders of last resort.

The main hurdles are not technological: To be clear: major technological hurdles do indeed exist to launching a credible, secure, and reliable CBDC. But these challenges can be addressed. The more difficult issues to address are policy and policy coordination in nature.

While distributed ledger technology may incorporate some inherent safeguards against hacking, central banks seeking a digital version of their national currency will require adjustments. Those changes may delay deployment in order to complete the development work. It will take time for central banks to solve issues regarding anonymity, data privacy, and regulatory reporting. Again, these are surmountable issues.

But for any digital currency to operate at scale, it must be interoperable on a cross-border basis. An elaborate cross-border payments system already exists to support international payments (large and small). As the deputy governor of the Bank Negara Malaysia noted in early August, much larger challenges await central banks seeking to issue CBDCs. Cross-border clearance and settlement will require policymakers to agree internationally on a broad range of standards, particularly:

- payments/clearing protocols

- information sharing

- data privacy

These are not technological issues, but policy coordination challenges.

Views vary—sometimes dramatically—at the national level regarding those issues. Laws in many jurisdictions restrict what kind of information can be shared across borders (and even across functions within the same country) with respect to private individuals and private firms. More stringent national security requirements apply regarding the sharing of information that pertains to core government functions like currency issuance.

The list above, while daunting, is not complete. Other policymakers this year and last year identified major issues regarding monetary policy transmission functions associated with floating a parallel, digital, currency alongside traditional currency. As an August 24 BIS Working Paper 880 noted, even the most advanced CBDC experiments in Canada, China, and Sweden stop short of creating concrete substitutes for cash. Current architecture decisions suggest all central banks are cautiously seeking to complement the role of cash with digital versions that often increase the role for a broad range of intermediaries.

Reserve currency competition: Caution does not decrease the imperative to compete. As Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard noted in a speech earlier this month, central banks have been spurred to accelerate their own experimentation efforts in response to both private market developments (the Libra proposal) and China’s rapid progress.

“The introduction of Bitcoin and the subsequent emergence of stablecoins with potentially global reach, such as Facebook’s Libra, have raised fundamental questions about legal and regulatory safeguards, financial stability, and the role of currency in society,” she said. “This prospect has intensified calls for CBDCs to maintain the sovereign currency as the anchor of the nation’s payment systems. Moreover, China has moved ahead rapidly on its version of a CBDC. With these important issues in mind, the Federal Reserve is active in conducting research and experimentation related to distributed ledger technologies and the potential use cases for digital currencies.”

Like all disruptors, China may be the first to deploy digital currency solutions at scale in its centralized economy. But speed is not the sole component required for success. The history of innovation suggests that established incumbents can successfully pivot and maintain a dominant market position if they can address market needs within a reasonable period.

The hurdle rate for shifts in market activity regarding reserve currencies is famously high, as noted in our first post. But the rise of China concomitant with rapidly scaling payments technology suggest that the reserve currency incumbents do not have an infinite runway to support deliberative processes.

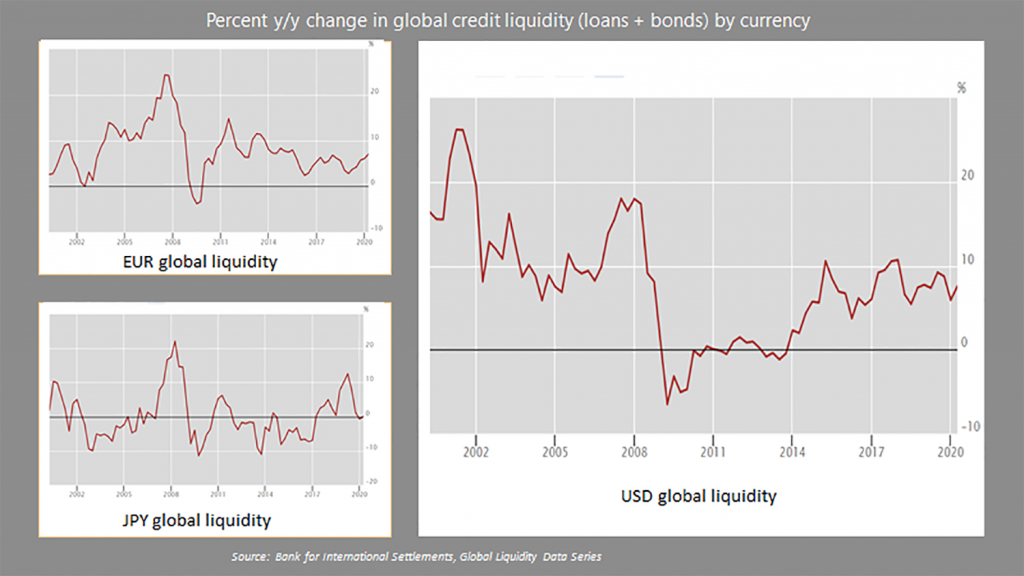

Data from the Bank for International Settlements shows that global reliance on the three major global reserve currencies has failed to recover from the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2012:

The BIS global liquidity data measures offshore aggregate credit exposure from banks and bond markets for each of the three major global reserve currencies. Neither the euro nor the US dollar has managed to sustain market levels above 20 percent since 2008. Offshore reliance on the Japanese yen began plummeting in 2019.

In other words, offshore borrowers continue to shy away from exposures denominated in foreign currencies. How much of this slide is attributable to overall decreases in credit exposures following the Great Financial Crisis is a question for another day. The point is that for any given level of credit intermediation, reliance on global reserve currencies has been dropping, even without credible alternative stablecoins.

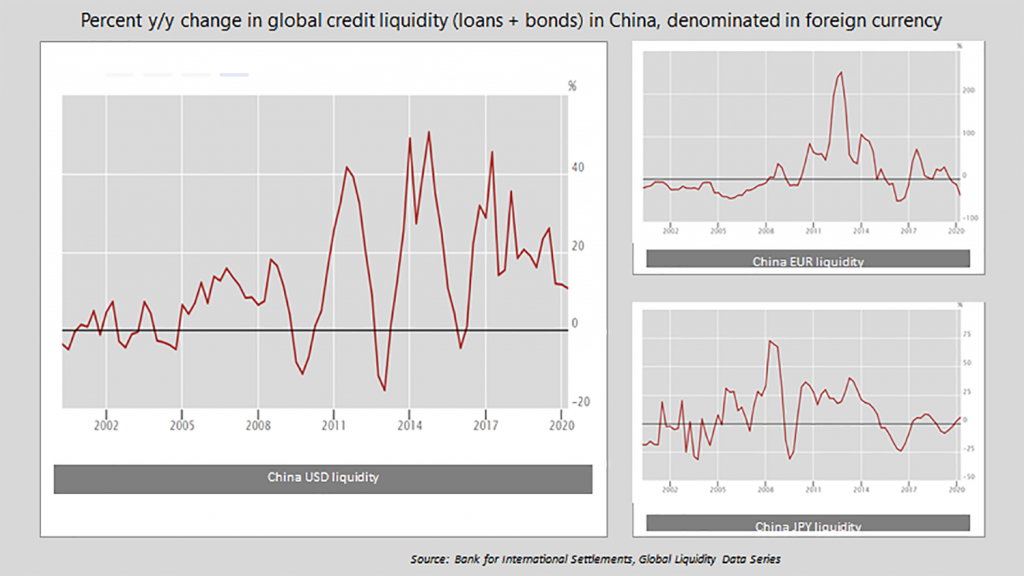

BIS data also sheds light on how the main disruptor in the global financial system (China) is interacting with the reserve currencies:

China has been steadily decreasing its reliance on euro liquidity since 2013 (shortly after the EuroArea sovereign bond crisis). A more jagged but generally declining reliance on US dollar liquidity is also clear starting in 2017. Reliance on the Japanese yen has been unsurprisingly tepid given the regional rivalry in East Asia.

Markets generally obsess about Chinese government ownership of US government bonds, but the real reserve currency pressure points may actually be in the FX markets in the medium-term. Advanced economy central banks seeking to maintain their prominence as reserve currencies will likely need to provide a younger generation of borrowers with internationally interoperable versions of their currencies in order to ensure continued strong market demand. Competition from China and private issuers will not let the established incumbents sit on the sidelines for long.

Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. She is also CEO of BCMstrategy, Inc., a technology company using patented processes to measure public policy risks. When in government, she served as the first US Treasury Attache to the European Union, with the Senate-confirmed diplomatic rank of minister-counselor.

Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, former executive managing director at the Institute of International Finance, and former deputy director at the International Monetary Fund.

Further reading:

Image: A general view of the Federal Reserve building in Washington, D.C., on May 21, 2020 (Graeme Sloan/Sipa USA)