DOHA—In the annual circuit of conferences attended by policymakers, think tank experts, academics, and business leaders, it’s rare to find yourself in the middle of history being made. But this past weekend at the Doha Forum—in which the Atlantic Council was one of almost four dozen partners this year—that was the case.

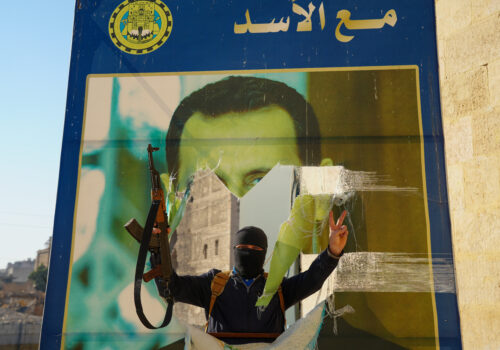

Many of us attendees were down the corridor or around the corner while the Russian, Turkish, and Iranian foreign ministers hurriedly met on Saturday, as the Syrian military was ceding territory to opposition groups and hours before Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad fled and surrendered Damascus. We watched on Sunday as Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan strode seemingly triumphantly into the main auditorium to address Forum attendees—though he was never on the original schedule to do so—while Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi abruptly cancelled his planned mid-afternoon speech and rushed home with the rest of the official Iranian delegation.

Araghchi returned to Tehran with his country in a weaker regional and global position than perhaps at any time since the 1979 Iranian revolution, a stark reminder of how quickly events can turn in the Middle East. Six months ago, many viewed Iran as being in the strongest regional position it had been in decades. Relations with Saudi Arabia had thawed following a rapprochement the previous year. In April, Tehran thought it had enhanced its deterrence by striking Israel directly with ballistic missiles and drones, a response to Israel’s killing of Mohammad Reza Zahedi, a senior commander in Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. Iran’s security ties with Russia were becoming more strategic, and its oil sales to China, in violation of US and other sanctions ignored by Beijing, continued to provide revenue.

The Assad regime is gone. Iran’s ability to operate directly (and through proxies) on the Israeli border is gone, too.

Equally important, Iran’s network of partners and proxies were ascendant. The Houthis in Yemen continued to undermine global shipping and disrupt international trade. Condemnations of Hamas’s October 7, 2023, attack on Israel had long since been pushed aside, and international attention was focused almost exclusively on Israel and its military operations in Gaza. And Hezbollah, the crown jewel of Iran’s network, was continuing to fire rockets from Lebanon into Israel on a daily basis, with the group’s massive weapons inventory more robust and lethal than ever.

Over the past half year, however, Iran’s regional position has completely flipped. The United States and its allies have rallied to Israel’s side to help defend it against Iranian and Houthi attacks, while Israel has demonstrated that its military is much more advanced than Iran’s. One has to wonder whether Iran asked Russia for a refund on the S-300 air-defense systems that did nothing to prevent Israel from striking Iranian military sites (and probably nuclear facilities) in October. Hamas and Hezbollah have been tremendously diminished, their leadership—not just at the top, but three and four rungs down the chain of command—killed or seriously injured, the majority of their weapons inventories destroyed.

In Syria, it’s all gone—everything Iran worked for and dedicated so much blood and treasure to protect for the past dozen years. The Assad regime is gone. Iran’s ability to operate directly (and through proxies) on the Israeli border is gone, too. And the land bridge through which Iran armed Hezbollah, providing a critical deterrent against Israel, is gone, at least in the short term. (Israel will almost certainly do whatever it can to extend that duration as long as possible, as well.)

It would be naïve to think this was all part of Israel’s plan. The reality is that Israel’s strikes against Hezbollah were designed to undermine the daily threat the group posed to Israel. Hezbollah today is so diminished that it abandoned its assassinated leader Hassan Nasrallah’s promise to keep striking Israel until there is a ceasefire in Gaza. The Lebanese Armed Forces—if properly trained, supplied, and advised—could in the coming years legitimately rival Hezbollah and help prevent it from serving as a perpetual spoiler in Lebanon, as envisioned in the November 27 ceasefire agreement.

But the unintended consequence of Israel’s strikes was to help buoy Syrian opposition leaders and convince them that the Assad regime, which was already weak, would not be able to rely on Iranian or Hezbollah forces to come to the regime’s aid. The opposition leaders were right.

Similarly, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and most other Arab states decided in May 2023 to invite Assad back into the Arab League after an eleven-year absence. It was, many in the region believed, a pragmatic response to the sense then that Assad wasn’t going anywhere. Was this decision part of a strategic vision to get Iran to pull away from Syria and eventually give up on Assad? Almost certainly not. And yet, some reporting indicates that warming ties with Arab governments also may have had the unintended consequence of hastening Assad’s fall.

Unintended consequences go both ways, however. Given how much has changed for Iran in the past six months, the story could be entirely different six months or a year from now. Perhaps at next year’s Doha Forum, we will witness the Iranian foreign minister engaged in frantic meetings for a much different reason: because Iran is sprinting for a nuclear bomb, viewing it as the only way to enhance deterrence and ensure regime survival in its current weakened state and feeling compelled to take riskier actions to survive. Or perhaps it will be the US secretary of defense defending a decision by the United States to join Israel in striking Iran’s nuclear program to prevent it from obtaining that outcome.

Neither of these is the most likely scenario, but the odds of either, or both, are higher today than they were in June. In the Middle East, the biggest developments are too often driven by unintended consequences, not strategy.

Jonathan Panikoff is the director of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and a former deputy national intelligence officer for the Near East at the US National Intelligence Council.

Note: The author’s travel to the Doha Forum was sponsored by the government of Qatar.

Further reading

Sun, Dec 8, 2024

Experts react: Rebels have toppled the Assad regime. What’s next for Syria, the Middle East, and the world?

New Atlanticist By

Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad has been ousted as opposition forces quickly took the Syrian capital. Atlantic Council experts share their insights on the developments.

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

Mon, Dec 2, 2024

In its final days, the Biden administration should take this step to support Syrian victims

New Atlanticist By Mohamad Katoub, Alana Mitias

The outgoing administration could direct up to $600 million in forfeited funds to support victims in Syria—but time is running out.

Image: The Atlantic Council’s Jonathan Panikoff speaks at the beginning of a panel discussion at the Doha Forum on December 8, 2024, in Doha, Qatar. (Credit: Sarah Zaaimi)