The road to Damascus was surprisingly short. On Sunday, Syrian rebel groups took control of the capital after a lightning-fast offensive across the country. Dictator Bashar al-Assad abdicated power and left Syria, according to Russia, his most powerful patron. How did this happen so swiftly after such a long period of stasis in Syria’s thirteen-year civil war? And what comes next for Syria, the Middle East, and the external powers that have been shaping events there? Below, our experts answer these urgent questions and others.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Rich Outzen: The Middle East’s power balance has rapidly shifted. The US will need a new strategy.

Qutaiba Idlbi: Assad’s fall is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the region

Gissou Nia: Assad should still be held accountable under international law. Here’s how.

R. Clarke Cooper: Russia is losing its Middle Eastern power projection—and great-power claims

Mark N. Katz: Assad’s fall may not be a total loss for Putin

Danny Citrinowicz: With its proxies crumbling, Iran will rethink its security strategy

Emily Milliken: Will Yemen’s Houthi rebels be the next Iranian proxy to fall?

Thomas S. Warrick: Postwar planning for Syria is now at the top of the agenda

Arwa Damon: Among Syrians, there is a sense that nothing is guaranteed and everything is possible

Sarah Zaaimi: The new Syria could normalize relations with Israel and reshuffle the region

Richard LeBaron: Arab leaders won’t like the shattering of Syrian stability

Karim Mezran: Libya offers important lessons for Syria’s next steps

Joze Pelayo: The new Syria can be a friend to the US—if the Trump administration seizes the moment

Alex Plitsas: There is much to be done to prevent a terror sanctuary from emerging

Nicholas Blanford: Hezbollah is now in the worst position of its four-decade history

Daniel Mouton: There are three scenarios for Syria’s future—and the US can shape which one emerges

The Middle East’s power balance has rapidly shifted. The US will need a new strategy.

The fall of the Assad regime less than two weeks into a coordinated assault by a broad array of opposition groups has, with shocking speed, changed the map and power balance in the Middle East and beyond. The long suffering of the Syrian people under a brutal regime that killed, tortured, dispossessed, and exiled millions of its people has ended. The Iranian hegemonic project in Syria, too, has ended, and with it Hezbollah’s privileged position. While the future of Russian bases, the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces in northeast Syria, interim governance, counter-terror activities, and Syria’s new role in the region may take months to take shape, it is clear today that Syria will be ruled by an opposition coalition with the support of a majority of Syrians.

Several analytic toplines stand out at this early stage. First, Assad’s hold on power was far more tenuous than was broadly perceived internationally, especially by those counseling reconciliation and normalization. Second, Iran and Russia have suffered a dramatic loss of influence in Syria and the region as a result of wars in the Middle East and Ukraine, making it impossible for them to save Assad in 2024 as they did in 2014-15. Third, Turkey is the only country that seems to have had a winning strategy for Syria: opposing Assad while negotiating with his backers, hosting refugees, supporting the opposition politically and militarily, and combating the People’s Defense Units (YPG), an offshoot of the anti-Turkey terror group Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), in northern Syria. Ankara now has unrivaled economic, diplomatic, and military leverage over the stabilization and rebuilding process, and the goodwill of an overwhelming number of Syrians. Fourth, the US approach to Syria for the past decade—tolerating Assad and his Iranian patrons, hyper-focusing on the Islamic State, providing humanitarian assistance but ceasing political and military aid to the opposition, giving open-ended support to the YPG/PKK—has collapsed. Washington, and Jerusalem, will have to come up with a coherent and constructive approach to the new management in Damascus.

—Rich Outzen is a geopolitical consultant and nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Turkey Program with thirty-two years of government service both in uniform and as a civilian.

Assad’s fall is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the region

The Assad regime, which has ruled Syria since 1971, was deeply authoritarian, a key part of Iran’s regional influence and the destabilization of the region, and the author of countless human rights abuses. Its collapse presents both challenges and opportunities for Syria, the region, and the international community.

Syria

The fall of the Assad regime could pave the way for political reform, democratization, and the rebuilding of a war-torn nation. With Assad gone without resistance, there is an opportunity to create an inclusive government that represents Syria’s ethnically and religiously diverse population, fosters economic recovery, and allows refugees and internally displaced persons to return. The Biden administration should work with international partners to support a transition to such a government, and ensure that all stakeholders, including opposition groups, civil society, and minority communities, have a voice in shaping Syria’s future. The Biden administration should also prioritize immediate stabilization and humanitarian funding to rebuild infrastructure, provide healthcare, and support the momentum for a quick return of refugees and displaced persons. The resumption of the United Nations (UN)-led Damascus-based humanitarian response across Syria to prevent the situation morphing into chaos is also an important step to support.

While engaging with Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), a US- and UN-designated terrorist organization, will present its challenges, the designation presents important leverage for the United States and international partners. The Trump administration, through dialogue with Turkey, could use that leverage to ensure HTS walks the walk as an acceptable actor within the Syrian scene and affirm it is no longer threatening US or regional security. The next US administration, working through international organizations, should also focus on fostering economic recovery and preventing the re-emergence of extremist groups.

The region

Assad’s fall completely disrupts the influence of Iran and Hezbollah, which have heavily supported and depended on the Assad regime. It will also decrease sectarian tensions fueled by the regime’s survival, reducing the risk of regional spillover conflicts. The United States should use this opportunity to coordinate a more firm regional policy toward Iran’s malign activities. Moreover, a power vacuum in Syria could lead to regional instability and risk Syria becoming a field for regional competition over hegemony, potentially creating more chaos and empowering extremist groups if not appropriately managed.

A stable, post-Assad Syria could catalyze peace and cooperation among neighboring states, but that requires serious diplomatic engagement from the United States with the region. To that end, the United States should engage in multilateral diplomacy with Turkey and Qatar and mediate responses with key regional stakeholders, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and Jordan, to ensure a coordinated approach to Syria’s stabilization. Encouraging dialogue between adversarial states could also help reduce tensions and foster cooperative security arrangements.

The United States

For the United States, Assad’s collapse helps counter terrorism, curb Iranian influence, and promote stability in the Middle East. The fall of Assad will end his regime’s policy of sponsoring terrorism, which lasted for decades. It will weaken alliances between Iranian proxies and diminish the power of Russia in the region. However, it also poses the risk of prolonged instability, requiring the United States to engage diplomatically in shaping the outcome. US sanctions could be a helpful tool if sanctions removal could be linked with concrete progress toward a stable and inclusive governance model that contributes to the region’s stability.

The fall of the Assad regime presents an opportunity to address longstanding issues in Syria and the region. However, it is not a panacea and could lead to further instability if not carefully managed. The Biden and Trump administrations must adopt a balanced and strategic approach, focusing on inclusive governance, humanitarian support, and regional stability. An opportunity of the kind that now presents itself in Syria comes only once.

—Qutaiba Idlbi is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs where he leads the Council’s work on Syria.

A moment for Israel and Gulf states to reshape the region’s future rather than react to it

The overthrow of the Syrian regime was so long coming and yet, shockingly, so rapidly achieved. The fall of Assad provides immediate closure on his rule in Syria, even as his horrific brutality will continue to echo for decades. But the sudden end of the Assad era leaves open the question of what comes next—with significant reasons for caution and concern that there could be fragmentation and chaos in the country. But no matter what follows in Syria, the implications of Assad’s departure will reverberate throughout the region.

For Israel, the overthrow of the regime is almost certain to be seen with mixed emotions, as the Israelis are uncertain if the devil they know will ultimately be replaced by a new devil they won’t. But there is opportunity, as well. Israel is unlikely to take a public victory lap but is entitled to one. The reality is that it was Israeli strikes in Lebanon over the last few months against a wide range of Hezbollah officials and weapons caches, and strikes in Syria preventing resupply to Hezbollah, that weakened the group to the point that Syrian opposition forces felt confident they could take advantage and try to capture Aleppo. Doing so required opposition forces to be confident that there wouldn’t be (sufficient) reinforcements to the Assad regime from Hezbollah, as had been a key issue in the past.

While Israel may not have intended or planned for the Syrian opposition to take advantage and use this development to overthrow the regime, Israel would be wise to immediately leverage it as a point of commonality and use it to seek out a quiet, private engagement with emerging leaders. If Israel wants to better ensure its security in the north, it should reach private, serious agreements with a new Syrian government that the country won’t be used to transfer weapons to Hezbollah to rebuild the group. Having a Lebanon that is in line with the Taif agreement and not dominated by Hezbollah, and a Syria not allied with Iran, would better ensure Israel’s long-term peace and security than any amount of interdiction or other strikes could.

Gulf states—some of which had assumed the Assad regime was here to stay and re-welcomed him and Syria into the Arab League—are likely to have mixed reactions about his fall and the next steps they should take. While Doha might be more inclined to provide financial resources for whatever government emerges in Damascus, long-standing concerns by Abu Dhabi and Riyadh over Islamist-led governments, combined with a reluctance simply to give away free money, as opposed to investing in countries, may cause them both to wait to see what leadership actually emerges in Syria.

It’s too early to know if the overthrow of the Assad regime will bring greater prosperity to the Syrian people and security to the region—ultimately the Syrian people will determine their future governance. But moments like this are rare and all too fleeting. If Israel, Gulf states, and other regional actors are wise, they’ll take this moment as an opportunity to try to shape the region’s future and not just react to it.

—Jonathan Panikoff is the director of the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and a former deputy national intelligence officer for the Near East at the US National Intelligence Council.

Assad should still be held accountable under international law. Here’s how.

Syrians have worked thirteen long years to take down their dictator—and an even longer fifty-plus years if you count the whole of the now defunct Assad dynasty. The international community must center Syrians in this moment, respect their aspirations for their country, and support them in achieving the pluralistic vision of a free, democratic Syria that so many fought for with their lives and livelihoods.

Even before the shock of Assad’s overthrow has worn off, Syrians who have spent more than a decade working on political processes, justice initiatives, and social change are swinging into action to realize the goals of their hard-won revolution.

On the justice front, the international community, global institutions, and national courts can take immediate action to support Syrians.

First, the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) can hold Assad and his former officials to account by swiftly opening a preliminary examination into transboundary crimes in the Syrian conflict. The ICC’s mandate in the matter would be limited to crimes against humanity of deportation, persecution, and other inhumane acts committed against Syrian civilians who fled to Jordan, an ICC member state. However, initiating a preliminary examination into these crimes would send a strong signal that the ICC is fit for purpose and that Assad will not continue to enjoy impunity for some of the worst crimes committed in this century. And ICC member states can support this push by making their own referrals to the court, similar to their referrals on Ukraine, Palestine and Afghanistan. In tandem, efforts should be made to encourage any interim government in Syria to accept the jurisdiction of the court, similar to how Ukraine did in 2014, with a path to eventual ICC membership once a proper governance structure is established and laws passed.

Second, France can proceed with its Assad case. In June a French appeals court upheld an arrest warrant against Assad, then a sitting head of state, for chemical weapons attacks against Syria’s civilian population. This was precedent setting, due to questions around Assad’s head of state immunity. With that question no longer in dispute, the proceedings should move ahead and with the option for in absentia trials in the French system—where the defendant does not have to physically appear. This means that Assad’s reported presence in Moscow with a refusal to appear or inability to be extradited will be irrelevant to evidence being heard on this critical chapter in Syria’s conflict. This case in France is just one of many universal jurisdiction processes that are currently done, in progress, or anticipated in national courts with the ability to prosecute alleged perpetrators in the Syrian conflict for war crimes and crimes against humanity. All those processes must continue and be supported by outside countries, particularly as more former Assad regime officials responsible for violations may try to leave Syria in this moment.

Lastly, there will be open questions about what will happen to the case that The Netherlands and Canada have brought against the Assad regime at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for violations of the Convention against Torture. Because the ICJ adjudicates disputes between states and not against individuals, Assad himself would not “stand trial” there—rather this will fall into a new twist on a gray area that other country disputes have found themselves in, such as those involving the former Yugoslavia, Myanmar, and the Taliban. Either way, Syrian victims and survivors should be centered in these considerations and all attempts made to secure justice and redress for them.

—Gissou Nia is the director of the Strategic Litigation Project at the Atlantic Council. She previously worked on crimes against humanity cases before the International Criminal Court and is counsel on submissions to the ICC Office of the Prosecutor.

Russia is losing its Middle Eastern power projection—and great-power claims

The liberation of Damascus by Syrian rebels, led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which is designated by the United States as a terrorist group, reflects the increasing degradation of the multinational ground forces supporting the Assad regime. But it also reflects a likely catastrophic loss of Russia’s significant investment in the Assad regime and Russia’s foothold in the Mediterranean.

The collapse of the Assad regime represents a contraction of Russia’s ability to project power in the region—and thus its claim of being a great power. Russia may now face losing a warm-water naval base as well as an air base. The damage to Moscow’s ability to maneuver in Africa and the Mediterranean may have a strategic impact on Russian influence across the world.

—R. Clarke Cooper is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and is the founder and president of Guard Hill House, LLC. He previously served as assistant secretary for political-military affairs at the US Department of State.

Assad’s fall may not be a total loss for Putin

The fall of Syria’s Assad regime, which Moscow had backed for so many years, is a severe blow to Russian influence in the Middle East. There is, however, one silver lining in it for Moscow: the fall of the pro-Russian Assad regime will not lead to its replacement by a pro-Western regime, as occurred in the “color revolutions” of earlier years. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s ongoing good relations with other Arab governments—including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, and Egypt—are also likely to remain strong.

The real question now is whether Russia will be able to keep its naval and air base in Syria. The anti-Assad forces that have just prevailed may not be inclined to let them stay—especially since Russian warplanes based in Syria had repeatedly bombed them right up until recently. If, however, a power struggle now ensues among the victors in Syria, this may provide Moscow with an opportunity to work with some against others. One possibility is Russian support for an Alawite statelet along the Mediterranean coast where its two bases are located (the Alawite minority was the backbone of the Assad regime). Moscow can even cite US support for the Syrian Kurdish statelet in northeastern Syria as setting a precedent for Russia doing something similar for the Alawites.

Still, Moscow retaining its naval and air base may not be possible, either because a new Sunni-dominated Syrian government proves to be strong and expels the Russians or because Syria descends into such chaos that the safety of the bases cannot be maintained.

—Mark N. Katz is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and professor emeritus of government and politics at the George Mason University Schar School of Policy and Government.

With its proxies crumbling, Iran will rethink its security strategy

The fall of Assad is another nail in the coffin of Iran’s Axis of Resistance, which will prompt Tehran to reconsider its security strategy.

In a matter of weeks, Iran lost its pillars in the Axis of Resistance. After the heavy blow that Hezbollah suffered at the hands of Israel, the fall of Assad is a fatal strike on Iran’s influence efforts in the Middle East. There is of course a connection between the two, since it is clear that the weakness of Hezbollah and especially the elimination of its leader Hassan Nasrallah, who was personally committed to saving Assad, accelerated the overthrow of the Syrian regime.

It is difficult to overstate the importance of the Assad regime to Iran. Without him, Iran’s ability to rebuild Hezbollah’s power has weakened dramatically, as has its ability to threaten Israel from this arena. But above all, Syria enabled the same territorial continuity from Iran to Lebanon that established the “Shia crescent” and gave Iran unprecedented strategic depth while keeping the wars away from its borders.

But the collapse of the regime shows how much the tools in Iran’s hands to save Assad without Hezbollah were almost non-existent. This fact also indicates Iran’s weakness and its limited ability to influence what happens in the Middle East without its proxy. Now Iran will have to calculate a new course and find a solution that will strengthen its ability to deter Israel and the United States on its own, with no real support of its proxies.

Iran will likely now seek to strengthen its conventional capabilities, including fast-tracking its Su-35 deal with Russia, rebuilding its air defense system, and replacing its missiles that were damaged in the Israeli attack. But Tehran will also likely think about whether to update its nuclear strategy, either to advance toward a nuclear bomb or to submit more significant compromises to the West in hope of reaching a nuclear agreement that will reduce the danger of an external attack on Iran. And so, the dramatic events in Syria also require a focus on what is happening in the decision-making circle in Tehran.

—Danny Citrinowicz is a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs and a member of the Atlantic Council’s Iran Strategy Project working group. He previously served for twenty-five years in a variety of command positions units in Israel Defense Intelligence.

Will Yemen’s Houthi rebels be the next Iranian proxy to fall?

The fall of the Assad regime removes yet another major node in Iran’s network of allies and proxies, making the Houthi rebels in Yemen an even more indispensable ally. Yemen’s Houthis and their leader, Abdul Malik al-Houthi, have already assumed a more prominent role within Iran’s Axis of Resistance after the loss of key leaders within Hamas and Hezbollah such as Yahya Sinwar and Hassan Nasrallah. The loss of the Assad regime will strain Iran’s presence and influence in Syria, meaning that Tehran may double down on its support for the Houthis—who have continued claiming attacks on Israel and international maritime traffic in recent weeks—as a means to maintain influence in the region.

However, the regime’s ability to provide the Houthis with resources—including arms shipments—could be impacted due to possible disruptions to Iran’s supply routes that run through Syria as well as Iraq and Lebanon. At the same time, Yemeni government forces and their allies in the region may find inspiration in the Syrian rebels’ success in overthrowing the Assad regime and undertake a new effort to militarily expel the Houthis in Yemen, potentially reigniting the war after almost three years of relative calm in the country.

—Emily Milliken is the associate director of media and communications for the N7 Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

Postwar planning for Syria is now at the top of the agenda

The United States was not directly involved in the ouster of Assad, but the United States has a huge stake in what comes next. A more stable Syria that frees itself from Iranian and Russian dependence, doesn’t export terrorism, lets its refugees come home, stops being a transit country for aid to Hezbollah that threatens Israel, stops treating the drug Captagon as a source of foreign exchange, and eventually lives alongside Israel in peace, perhaps joining the Abraham Accords in time: all these unthinkable things are now possible. But this will not happen spontaneously, without outside help and support. Postwar planning for Syria needs to go into high gear.

The basic infrastructure exists to give immediate aid to the Syrian people, but it needs funding and political support from the United States, along with European and Middle Eastern countries. The immediate question for the Biden administration is whether to allow the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and other US-backed aid agencies to send urgent help into Syria. And while the United States has limited ties with HTS, which Washington has designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization, HTS is not the only group in the Syrian opposition that now controls Damascus. Who is dominant among those groups depends on who gets what kind of external aid. While Turkey’s aid to these groups is done to support Turkey’s national interests, most of Turkey’s interests and the United States’ are aligned in western Syria. The United States can cooperate closely with Jordan and Israel, with whom its interests are also aligned.

The incoming Trump administration will have different voices competing for Trump’s ear. The isolationist wing will be arguing that other governments should take the lead in postwar Syria. While those voices are not totally wrong, other voices will remind Trump that weakening Iranian influence, supporting Israel’s security, and peace in Lebanon are, collectively, one of the biggest wins that a Trump administration could hope to achieve. Peace in the Middle East is one of Trump’s greatest ambitions, and if he listens to the right advisers, he could go a long way toward achieving it.

—Thomas S. Warrick is a nonresident senior fellow in the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative and a former deputy assistant secretary for counterterrorism policy in the US Department of Homeland Security.

Among Syrians, there is a sense that nothing is guaranteed and everything is possible

There is a certain pragmatism to what we are seeing now in Syria, not just in how the fighting forces coordinated but also in the attempt to preserve a temporary governance structure. The lessons of past failures are being taken into consideration, although it’s too soon to tell if it’s just lip service or if it will hold. What has transpired over recent days, though, is in many ways uniquely Syrian—coming at a time when most of the world had shown a willingness to write off Syria and the hundreds of thousands killed, tens of thousands detained, and millions displaced, and to “normalize” relations with the Assad regime.

“Stay out of it” is a message I’m hearing from a lot of Syrians who have already learned the bitter lessons of both abandonment and extreme meddling by external actors. Syrians will be quite reluctant to trust any form of outside interference. But at the same time there is an awareness that the country’s new leadership will need to make compromises and bargains. There is a recognition that nothing is guaranteed, and that Syria’s future is filled with risks and the potential of more violence—be it in the form of a civil war or Israel encroaching on more Syrian territory. There is a certain wariness, apprehension, and anxiety coupled with the elation that we’re seeing. No one knows at this stage what is going to happen next. Everyone is spinning, from those in the streets to those in governments around the world.

—Arwa Damon is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs; the president and founder of the International Network for Aid, Relief, and Assistance (INARA); and a former international correspondent for CNN.

The new Syria could normalize relations with Israel and reshuffle the region

After more than sixty-one years of the Ba’ath party’s rule and thirteen years since the uprising ignited in Daraa, Syria’s agony has finally reached a denouement, and the Syrian people can finally obtain closure and reclaim agency over their political future. While other Arab Spring countries were able to topple tyrannical leaderships and change regimes with varying success or failure, Syrians were held hostage by foreign powers’ interference and calculus, which maintained Assad at the top of a failed political system and forcibly displaced more than fourteen million Syrians internally and externally. These events also mark the end of the last of the Nasserist Arab nationalist regimes in the region—the end of an entire despotic ideology.

The current political alternative to Assad is far from ideal as the opposition remains fragmented. Rebel leader Abu Mohammad al-Jolani has a questionable past tied to international terrorism, and the rebel factions have various allegiances to regional powers, especially Turkey. However, the Syrian people should be allowed to determine their own sovereignty and to establish the transition of power they wish for their country without international guardianship. They will also have to resolve some existential questions about relations with their immediate neighbors. It is not out of the realm of possibility to imagine new leaders in Damascus normalizing relations with Israel and reshuffling regional dynamics to mark a true rupture with the Ba’athist doctrine.

Once the dust settles, there will surely be arduous negotiations over Syria’s future among the new masters of the land, yet initial indications seem promising. So far, the rebels are maintaining a plural and inclusive discourse calling for national unity and a peaceful transition of power. Jolani gave instructions not to desecrate shrines and minority cultural heritage sites, such as the Sayyeda Zaynab sanctuary. Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) militants had vandalized the shrine, a revered location for Shia Muslims, and the incident became one of the reasons Shia militias, especially Iraqi Popular Mobilization Units, engaged in fighting in Syria. Even the traditionally pro-Assad Alawite cities, including Latakia, seem to be relieved that the Assad era is over, which is a positive indication that minority groups would likely join the political transition rather than engage in yet another costly civil war.

—Sarah Zaaimi is a nonresident senior fellow for North Africa and deputy director for communications at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center & Middle East programs.

Arab leaders won’t like the shattering of Syrian stability

Regimes in the Middle East most value stability. Political change of any kind, violent or non-violent, is considered a threat, not an opportunity. So there will be no congratulations for the Syrian people emerging from Arab leaders and no rush to embrace a new regime that is likely to be dominated by Sunni fundamentalists. There is unlikely to be a rapid response to the needs of the Syrian people as they emerge from the nearly fifty-four-year rule of the Assad family. Most Arab states were openly supportive of Bashar al-Assad, preferring a cruel, Iranian-supported dictatorship to any other options.

Among Arab states, perhaps only Qatar, which supplied aid to some Syrian opposition forces, will step forward to help now. Syria’s neighbor Israel has long preferred the quiet that the Assad family was able to impose on their border and will be wary of what comes next. Most Arab states (and Israel) will also view the revolution in Syria as a net plus for Turkey and therefore a net minus for Arab interests. Meanwhile, Assad’s supporters in Moscow and Tehran will be left to wonder how things went so badly so quickly.

—Richard LeBaron is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He is a former US ambassador to Kuwait and a former deputy chief of mission at the US embassy in Israel.

Libya offers important lessons for Syria’s next steps

It’s true that making comparisons between different countries is always a delicate and insidious effort. Nevertheless, the recent events in Syria bring to mind the events in Libya that brought the Qaddafi regime to a bloody end in 2011. Has Libya’s recent history anything to teach to Syria and its people?

While joyful manifestations and apparent happiness are welcome and to be expected, they should be limited in time and scope so as not to alienate and marginalize the supporters of the previous regime (even if they only consist of a small minority). This would with time form a hardcore group of opponents to any process of opening up and developing institutions. In other words, regimes that have held power for decades have deep roots, and they can often do fatal damage in the aftermath of their ouster.

A second lesson Libya can teach Syria is how to deal with foreign powers, whether regional or global. Libyans allowed foreign powers to divide and separate them in order for each one of them to exercise at least a veto power on political and economic developments. The new Syrian elites should strive to find a common denominator among themselves, and instead of rushing to elections they should organize a National Reconciliation Conference to draft the main principles and values that apply to all Syrians. Only after this moment of deep reflection and foundation-building of a new national interest based on a shared identity should the country proceed to elections.

—Karim Mezran is director of the North Africa Initiative and resident senior fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center and Middle East Programs at the Atlantic Council.

The new Syria can be a friend to the US—if the Trump administration seizes the moment

The transition in Syria presents an opportunity for the United States to regain influence in Damascus and encourage any emerging Syrian authority to contribute to regional stability, coexistence, and peace. The incoming Trump administration should prioritize assisting a transitional government in holding free and fair elections, enabling Syrians—who have endured years of brutality under dictatorship—to shape their own future. A future Syrian administration is likely to welcome US support and may even become a friend of the United States, given the widespread animosity toward Iran and Russia due to their support for the Assad regime.

Will the new administration see this opportunity? At forums I have attended across the region over the past month—from Sir Bani Yas in Abu Dhabi to the Middle East Policy Forum in Dohuk and the Doha Forum in Qatar—policymakers and experts consistently expressed concern over the unpredictability of President-elect Donald Trump’s approach to the Middle East. His policies remain a mystery, likely subject to rapid change depending on the influence of his advisers and who’s the last person in the room with him. However, Trump needs to recognize the value in supporting an orderly transition and a stable future for Syria, where Iran and Russia’s influence has been significantly diminished.

The Trump administration should also seize the opportunity by facilitating dialogue between the new Syrian administration and Israel. And it should collaborate with Qatar and Turkey, which played critical roles in the rapid progress leading to this moment, to help reintegrate Syria into the rules-based international order.

—Joze Pelayo is an associate director at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative.

There is much to be done to prevent a terror sanctuary from emerging

On Sunday, Syrian rebel factions collectively defeated and ended the regime of Assad after a long and bloody civil war. Assad and his father before him were dictators who hailed from the Alawite Shia religious minority that accounts for approximately 10 percent of the Syrian population. They ruled with an iron fist, brutalizing and oppressing the remaining 90 percent of the population.

Assad’s departure is being widely celebrated by all facets of Syrian society. After thirteen years of fierce fighting, rebel groups of various ideologies, ethnicities, religions, and political agendas achieved what no state power has been successful at doing through the elements of power they have sought to employ.

With the fall of the regime, there will no longer be a Shia government in charge of Syria. This effectively ends the famed “Shia Crescent,” which allowed Iran to influence if not control foreign and security policy stretching from Tehran through Baghdad to Damascus and southern Lebanon. Unlike in Iraq, democratic elections in Syria will not produce a Shia-led government given the country’s demographics. This will make it more difficult for Iran to rearm and support Hezbollah and other proxies in the region, as Syria had served as a logistics hub for Iranian weapons. The land and air bridge that allowed Iran to arm and resupply Hezbollah and other terror groups and militias in the region is gone.

While there is much to celebrate—the end of Iran’s stranglehold, the promise of newfound freedom for the Syrian people—the road ahead is fraught with uncertainty and risk. In the past twenty-four hours, a rebel faction with historic ties to al Qaeda that was designated as a terrorist organization by the United States since 2018 has taken control of Damascus. Israel has seized territory in the buffer zone with Syria and bombed strategic weapons sites. And Turkey has bombed Syrian Kurdish rebels backed by the United States, according to reports I have seen from the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces.

The international community should seek to achieve the following objectives in Syria to prevent a failed state that can be used as a sanctuary and launching point for transnational terrorism:

- Prevent an escalation between rebel factions and encourage unity in victory

- Deny terror groups access to strategic weapons and systems left by the regime

- Protect ethnic and religious minorities

- Encourage and enable democratic institutions and elections

—Alex Plitsas is a nonresident senior fellow with the Middle East Programs’ N7 Initiative and former chief of sensitive activities for special operations and combating terrorism in the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Hezbollah is now in the worst position of its four-decade history

BEIRUT—The stunning and sudden collapse of the Assad regime threatens to greatly complicate the geostrategic links between Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon and raises the possibility that the Iranian-led coalition known as the Axis of Resistance is coming apart. Since assuming power in July 2000, Assad had been the linchpin connecting Iran in the east of the region to Hezbollah in the west, offering strategic depth, a source of weaponry and political support and serving as a conduit for the transfer of Iranian weapons. The critical importance of the Assad regime to Tehran was amply demonstrated more than a decade ago when Iran and Hezbollah took the unprecedented and controversial step of openly intervening in the Syrian civil war to protect their ally from being overthrown.

Now that Assad and his regime are gone, Hezbollah is isolated in Lebanon at a time when it is recovering from the blows of a devastating thirteen-month war with Israel. The November 27 ceasefire agreement between Israel and Hezbollah calls for the prevention of weapons being transferred into Lebanon from Syria. Although Hezbollah has said it will abide by the ceasefire agreement, the new realities in Syria suggest that even if the organization wanted to restock its arsenal with weaponry coming from Syria, it may no longer be possible. The collapse of the Assad regime will likely lead to the eventual emergence of a new form of governance that better reflects the Sunni-majority demographics of Syria, one that is unlikely to view Iran and Hezbollah with much warmth. That and the continued aggressive behavior of the Israel Defense Forces in Lebanon (the ceasefire notwithstanding) places Hezbollah in the most uncomfortable position in its forty-two-year history.

—Nicholas Blanford is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs.

There are three scenarios for Syria’s future—and the US can shape which one emerges

Given the enormity of the Assad family’s fall from power, it is impossible to predict the full extent of the effects on the region. Three possible futures await Syria:

- A perfect world: On the surface, the fall of the Assad regime appears to be a net positive for the United States and its allies in the region. A cruel despot is gone, and Iran no longer has a land-based supply line to its proxies in Syria and Lebanon. However, this future depends on Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and the other factions that banded together against Assad choosing to work together and govern responsibly. Due to the multiple groups and external actors in Syria, this path is unlikely to occur absent a responsible guiding hand.

- Chaos and violence: A more likely scenario, unfortunately, is a culmination of the same societal and religious-ethnic cleavages that have been witnessed across the Middle East because of the Arab Spring. Libya collapsed following the removal of Muammar Gaddafi, Yemen effectively remains mired in internal conflict, while other states in the region have largely recovered from or avoided the effects of the Arab Spring. Syria may follow the path of Libya and descend into chaos. Competition for power among Syria’s different armed groups would create havoc for the Levant region.

- Factionalization: This future would involve a continuation of many of the present partitions within Syria. While HTS recently expanded its control south through Damascus, other areas of the country remain under the control of other armed groups. Continued disunity and ungoverned spaces will allow for a resurgence of extremist activity, as well as the potential return of Iran and its proxies.

The United States can help determine which future comes to pass. Instead of watching events develop in Syria, the Biden administration could act to shape the initial steps taken by any new governing body in Damascus. First, active US diplomacy and humanitarian assistance could guide a new governing body while reinforcing the principles of inclusion and accountability. Second, Syria needs considerable reconstruction assistance. The amount of need will far outstrip the organizational ability of any new government, as well as the absorptive capacity of remaining Syrian institutions. The United States, other countries, and international organizations can fill organizational gaps and accelerate reconstruction efforts. Third, millions of Syrian refugees will want to return home and are more likely to do so in an environment of good governance and active reconstruction. Putting Syria on the path to recovery is the best insurance to prevent a return of Iran and its proxies, as well as a return of extremists operating out of ungoverned spaces.

Initial steps taken by the White House and the State Department will be instructive. If we see calls between US President Joe Biden and regional heads of state, and if we see regional diplomacy led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, then it will be an indication that the Biden administration is trying to fashion a positive future for Syria. Finally, if we see the appointment of someone resembling a Syria reconstruction envoy in the waning days of the Biden administration, this person may be able to use the intervening weeks before the Trump administration takes office to help guide the new government as well as channel regional assistance to Syria.

The region recognizes the need to rehabilitate Syria, so there should be no expectation the United States needs to pay for all of Syrian reconstruction. But the United States should take immediate steps to avoid the dire circumstances that played out in other post-Arab Spring countries. There’s no reason Syria’s future should be worse than its past.

—Daniel E. Mouton is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative of the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He served on the National Security Council from 2021 to 2023 as the director for defense and political-military policy for the Middle East and North Africa for Coordinator Brett McGurk.

The lesson for other Arab regimes—illegitimate governments cannot be propped up forever

Since 2011, Syrians have dealt with a double moral calamity: the sectarian vengeance of an endlessly brutal regime and the indifference of the outside world, even as Russian military and mercenary forces swept in to rescue it from collapse, and children were tortured, starved, or killed in staggering numbers.

As the Syrian people convulse with rapture and relief, the celebrations are no doubt stalked by sorrow and made heavy by the weight of more than a decade of darkness and loss. The joy of the present must also be tempered by a lack of clarity around what is to come. There are many moving parts in Syria right now, which means that there are many possible futures.

While Syria’s future is uncertain, there are clear messages for other Arab regimes. For example, rival governments in Libya and military rulers in Egypt have similarly hollowed out the state, turning to smuggling and crime to remain afloat and apart from their subjects, and inviting comparisons with gangsterism and the mafia. Recent events in Syria call into question the sustainability of this path, along with the broader strategy of accursing the population and spurning the very concept of legitimacy.

The fall of Assad also calls into doubt the value and dependability of a defense alliance with Russia, as well as the ultimate capacity of foreign militaries, militias, and mercenaries to indefinitely prop up governments that have been rejected by their people.

The seemingly removed and unconnected events of Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine in February 2022 and Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, have resulted in a butterfly effect in Syria, with consequences that will cascade through the region.

As for the United States, while Trump has made plain that he is not interested in developments in Syria, it is likely that, one way or the other, developments in Syria will be interested in him.

—Alia Brahimi is a nonresident senior fellow in the Middle East Programs and host of the Guns for Hire podcast.

Further reading

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

Could Syria’s rebels take Damascus?

New Atlanticist By Qutaiba Idlbi

Controlling Aleppo was a big deal for the Syrian rebels, and taking Hama was an even bigger achievement. But Damascus remains the real prize.

Mon, Dec 2, 2024

In its final days, the Biden administration should take this step to support Syrian victims

New Atlanticist By Mohamad Katoub, Alana Mitias

The outgoing administration could direct up to $600 million in forfeited funds to support victims in Syria—but time is running out.

Thu, Dec 5, 2024

What does Turkey gain from the rebel offensive in Syria?

MENASource By Ömer Özkizilcik

The rebel offensive took many by surprise, but analysts familiar with the situation in Syria were aware that the rebels were prepared to launch it by mid-October.

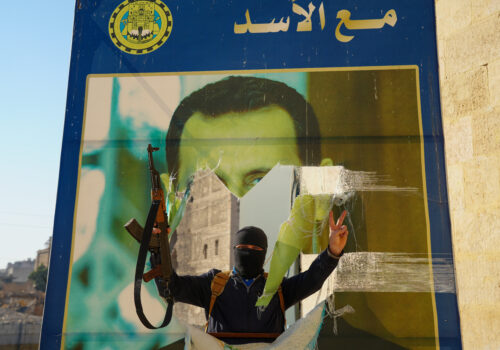

Image: A man holds Syrian opposition flags as he celebrates after Syria's army command notified officers on Sunday that President Bashar al-Assad's 24-year authoritarian rule has ended, a Syrian officer who was informed of the move told Reuters, following a rapid rebel offensive that took the world by surprise, in Aleppo, Syria December 8, 2024. REUTERS/Karam al-Masri