‘That is a weak spot for some,’ says Johan Verbeke, Belgium’s Ambassador to the United States

European nations need to do a better job of working together to detect, share, and act on intelligence related to terrorist plots, according to Johan Verbeke, Belgium’s Ambassador to the United States.

“There is information that we share with others, but we know it is not being used,” Verbeke said in an interview. “That is a weak spot for some.”

The Ambassador’s sentiment underlines a key challenge that faces Europe as it grapples with a terrorist threat as well as historic levels of migrants landing on its shores from war zones in mainly Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

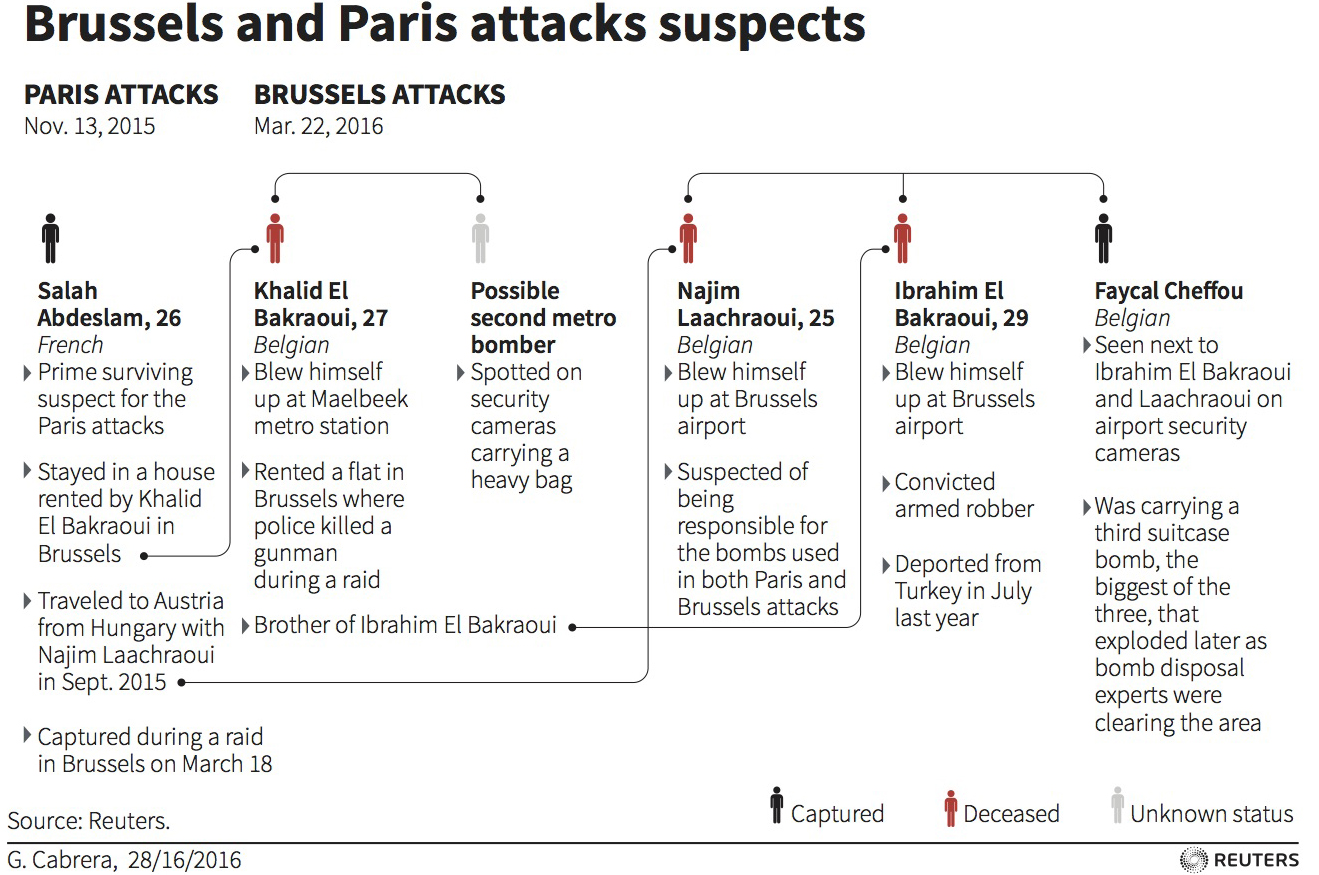

Europol, the EU’s police agency, had warned in January that Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) “special forces” planned to attack European cities in attacks similar to those carried out by a Pakistan-based terrorist group on Mumbai, India, in November of 2008. On March 22, terrorists struck at the heart of the European Union—Brussels—killing thirty-five and wounding more than 200 people. The attack took place a little over four months since terrorists attacked Paris on November 13, 2015, and killed 137 people.

Verbeke said European governments need to change their mindset in light of these attacks.

Belgian lapses

Belgian authorities themselves have been guilty of multiple intelligence lapses in the days leading up to the Brussels attacks. For instance, they failed to arrest one of the Brussels suicide bombers— Ibrahim el-Bakraoui—despite a warning from Turkey that he had been apprehended near the Syrian border last summer.

In another example, local Belgian police in the town of Mechelen acknowledged that they knew the address of a possible safe house of alleged Paris attacker Salah Abdeslam in December, but that information had not been uploaded into the national police database. Abdeslam was eventually arrested on March 18 in the Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek.

Verbeke defended the initial Belgian response. Since the Paris attacks, “we have been doing everything we could in order to start dismantling those networks,” he said.

Several house searches in the days leading up to Abdeslam’s arrest revealed that “there was more than just a kind of Brussels-Paris connection,” he added. “As of then, house searches have been a daily business. There have been hundreds of them.”

Not a failed state

The Ambassador dismissed uncharitable labels that have been used to describe Belgium—“failed state,” “a hotbed” for terrorism—especially after it was revealed that three terrorists who attacked Paris on November 13, 2015, had links to Belgium. Also, more Belgians have joined ISIS as a proportion of the population among Western nations.

In part, this has to do with the fact that Belgium, like much of Europe, has struggled to integrate its Muslim immigrant community. Yet, the challenge is more complex than simply declaring that marginalized or unemployed youths are vulnerable to terrorist recruitment.

Johan Verbeke spoke in an interview at his office in Washington with the New Atlanticist’s Ashish Kumar Sen. Here are excerpts from our interview.

Q: Belgian intelligence and security services missed vital clues in the lead up to the Brussels attacks. Does this failure point to deep structural problems in Belgium? What is Belgium doing to address these problems?

Verbeke: Let me just thank the Americans—officials and also the American people. The President [Barack Obama] called the [Belgian] Prime Minister [Charles Michel] the very day the attacks occurred; Vice President [Joe] Biden was in the embassy to offer his condolences; [US Secretary of State John] Kerry took a stopover in Brussels in what we know is his extremely hectic agenda. And then there have been just the American people. There is a kind of worldwide sympathy coming to our country.

Belgium’s determination to face up to the challenge has increased and not diminished in the wake of the attacks. There is no way that we will feel intimidated. The Belgian people have demonstrated a typically Belgian quality, that is a lot of serenity and coolness in their reaction to the attacks. On the very evening of the attacks a sober tribute was paid to the victims. That shows the maturity of the Belgian people. It is not that the world collapses, that Belgium collapsed. We stand on our feet and tomorrow we are back at our jobs.

To address your question, we have to avoid the reductionist simplifications that we have seen, regrettably, in certain parts of the press. The awareness levels in Belgium as regards to potential threats coming specifically out of ISIS, that awareness was there for over one year now. As of the very beginning of 2015, late 2014, that awareness was there. It was not just Belgium. It was more or less at that time that most of the capitals woke up and said: “Look, we have to be very prudent.” We were among the first, given the fact that we have a certain amount of foreign fighters that have gone to Iraq and that we knew would one day or another most probably come back.

The rate [of Belgians going to fight in Iraq and Syria] is high in terms of per capita, but the rate is not that high if you take the absolute figures—if you compare it, for instance, with the UK, which is well beyond the number of fighters that we have.

In February 2015, a very important network was dismantled in Verviers. That was the first active intervention that undid a cell that was close to becoming operational. As of that time, we have been working intensely on different files. The investigations and house searches started and, particularly after the Paris attacks, the whole enterprise gained momentum. As of then, I definitely am confident in saying that we have been doing everything we could in order to start dismantling those networks, having connections with other services all over Europe. That bore certain fruit.

People say, why did it take four months to grab Abdesalam [the Paris terrorist attack suspect]? The fact is that nobody knows exactly—in the kind of free Europe where you can travel from one place to another—where he was and at what time. We know for instance that he was at certain stations in Budapest, and then he traveled through Holland. So it’s not as if he was just sitting there and that we did not detect him.

A few days before Abdesalam was arrested there were a lot of house searches and these house searches were revelatory. That was a very crucial moment. At that time, it went into the minds of many people in Belgium in the security and intelligence community that there was more than just a kind of Brussels-Paris connection. As of then, house searches have been a daily business. There have been hundreds of them. Just [on March 27] there have been thirteen house searches. From time to time we could identify certain people and they were arrested. Some remained free because there was not a connection. We are a country where the rule of law is being respected so we have to make those distinctions between those whom we have to apprehend and those whom we cannot.

Saying that we are a failed state is definitely an exaggeration and a simplification. These are complex matters. We are seeing that many [European] capitals are struggling with this. Even the person that the French detected just a few days ago was around for more than a year. It is very difficult to find out exactly whom are you looking for, where are they hiding, what do they have in the offing.

Our security services have been working day and night and have been rather successful. We have arrested close to ten people who we know are active terrorists. [French] President [François] Hollande made a statement that he thinks that the Paris network has been severely dismantled. But we, in the meantime, have, we think, dismantled in a critical way that other network that was connected to the attacks of [March 22] and perhaps even some other attacks that may have been planned for the future.

Q: What are your thoughts on the level of intelligence cooperation among European governments?

Verbeke: Let me stress without any qualification that if there is one country that has been, including publicly demanding, that cooperation particularly among European countries should be increased, that is Belgium.

Our Minister of Interior has again and again stressed that we have to get our act together at the European level, including for the PNR [EU Passenger Name Record data]. We have been pushing the European parliament to get ahead.

In Belgium, one of the founding members of the European Union, we are genetically programmed to multilateralism. We know that a country of our size cannot but work together with the others. We are an extremely open country—we have an open economy and open society. We cannot but live with the world abroad. On that plane there is no blame whatsoever that can be directed against us. We have been exchanging a lot of information with others, we expect the others to do the same with us.

Incidentally, I would like to stress that the cooperation with [US] authorities, be it the intelligence community—the CIA—the FBI, Homeland Security, is working very well. We have here in the embassy a liaison officer and I drop by his office every morning just to check what is going on and again and again he tells me, “Again ten names that we have given to the Americans; again six answers that I got from the FBI, CIA.” That cooperation is really very, very good and very intense. And Secretary Kerry said [the same] in his press statement in so many words.

In that context, just ten days before the attacks, a US foreign fighter team wanted to come and see how we tackle the problem [of foreign fighters]. I haven’t seen the report, but I spoke with my liaison officer here and he confirmed that the report was very positive in terms of what we are doing on tackling the problem of foreign fighters.

The number of foreign fighters leaving Belgium today is one third of what it was one year ago. So the programs work, including the deradicalization programs. One of the mayors of Vilvoorde [Hans Bonte] was a guest at the White House and he was invited to come and speak about his deradicalization program because it was considered a model.

Q: What specific steps is Belgium looking at to enhance security and intelligence cooperation in Europe?

Verbeke: You have to detect information, share the information—that is crucial—and you have to use the information. There is information that we share with others, but we know it is not being used. To be fair, we also went through an intense exercise of awareness in terms of the telling the people, “Look, you have those lists, please use them.” At the end of the day you have to use the information, and that is a weak spot for some.

Q: Why do you believe this information is not used?

Verbeke: It is an institutional question. We have been working before this with a certain modus operandi. Now this new context in which we operate, given ISIS—but it can be terrorism from other sources as well, obliges us to change our modus operandi. To change our mindset and the way we work when you are in any function that is related to security.

“I think the external threats that we as Europeans face are an argument for solidarity and cooperation rather than for going your own way,” said Johan Verbeke, Belgium’s Ambassador to the United States. (Atlantic Council/Victoria Langton)

Q: Why has Belgium become what some commentators believe to be a hotbed of Islamic terrorism?

Verbeke: I have problems with stereotypes like hotbeds of jihadists and so on. These are simplifications. Just [on March 27] arrests have been made in connection with ISIS in Germany, Holland, Italy, and Belgium. It is not that everything is confined in Belgium.

This being said, we recognize that our country has been more exposed to the problem, which we see as the result of a few factors, one being that we had very aggressive [terrorist] recruitment in Belgium. There is no other country where the recruiting has been done in such an aggressive way.

We had a group called ‘Sharia4Belgium’. This is a group with which justice has been struggling for months, perhaps years. It was finally dismantled with a big legal trial where all of them were condemned, some in absentia. The head of that organization—Fouad Belkacem—had an extremely negative influence by bringing youngsters to meetings and that was the beginning of a brainwashing process that resulted in these people being convinced about the cause that ISIS stands for and leaving their homes for Syria.

We are a country that historically has a large Muslim community. In that respect, we are different from other places in Europe. We know that a sectarian movement [like ISIS] very often uses religion as a vehicle to transmit its message, which is extremely dogmatic.

As we have a large [Muslim] community that means that potentially some of them are going to be vulnerable. Just because of the logic of the numbers. I hasten to stress that we should definitely not [lump all] Muslims [together]. In that respect, it is quite significant how many Muslims, including Muslim organizations, have come to the vigils that take place every night at Place de la Bourse [in Brussels] and say with big placards, “Nous Sommes Belge (We are Belgian).”

More generally, we are a very international city. We are a very open country. Given our size, we must open our window to the outside word. There is a lot of coming and going and that perhaps also has contributed a little bit to our specific vulnerability.

Q: What is your government doing on de-radicalization and on improving the assimilation of Muslim communities?

Verbeke: In just Molenbeek, something like 700 community workers—who are close to vulnerable groups—have been activated. They speak with them; they do activities together. They work with non-governmental organizations who organize cultural events, the Mayor goes to speak to them, there are police people who go to the communities and tell them, “Look, we are here to protect you.”

Q: Will the attacks in Brussels force Belgium to shut its doors?

Verbeke: The answer is a clear and unqualified no. The reason is that whereas that kind of open-door policy, that openness, can become a problem as it is to some extent in the context of transnational terrorism, basically it is an asset. It makes our country, and particularly our city of Brussels, one of the most international capitals in Europe. Politico, on the eve of [President] Obama’s visit last year to Brussels, qualified Brussels as one of the most cosmopolitan capitals in the world. That is something of which we are extremely proud.

Q: Is the Schengen Zone today in peril as a result of a combination of the terrorist attacks and migrant crisis facing Europe?

Verbeke: If it depends on the Belgians, Schengen will survive. That is for sure. We have to see the benefits and the drawbacks. Of course now we stress the drawbacks because we are indeed facing a very important challenge that is immigration.

Schengen was not primarily meant to be a mechanism for building a bastion. As it was not meant to be a bastion, one should not be surprised that given this migration pressure now we have to adapt and to work out a solution, which is basically what our heads of government found at the last European Council.

I am confident that Schengen will survive. People don’t realize what the benefit of the system is. There are reports from economic agents saying the cost of Schengen disappearing would be tremendous. We would have to revisit all our business models. And that is just the economic reason.

Think also of the ease with which we go from one country [in Europe] to another. We have one open, free space of movement and that we should maintain because it also helps build that European community—the community of the people. It’s not just member states negotiating and making sure that the European project is going in the right direction. It is also the spirit of the people and ease of travel. Brussels to Paris today is one hour and twenty-five minutes [apart]. London is one hour and fifty minutes. You say, “Shouldn’t we go to London?” and you go to London. That’s it.

Q: Supporters of the Brexit point to the Brussels attacks as a strong argument for the United Kingdom leaving the EU. Why are they wrong?

Verbeke: It is incorrect because as we face a transnational threat, European and international cooperation is a necessary condition for tackling these issues. So withdrawing from the European network would mean that the British people would have to build out their own systems and so on. I don’t think it would help the British people. I think the external threats that we as Europeans face are an argument for solidarity and cooperation rather than for going your own way. I think it would be unfair to say that it is only an argument for Brexit. I have seen people arguing that you can as well make an argument out of it for staying in the European Union.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: “There is information that we share with others, but we know it is not being used,” Belgium’s Ambassador to the United States, Johan Verbeke, said of intelligence sharing and cooperation among European governments. (Atlantic Council/Victoria Langton)