President-elect Biden will assume office during an as-of-yet unabated global pandemic that has, as of this writing, killed nearly 240,000 Americans, destroyed years of economic growth, and revealed and reinforced persistent inequalities in US society. It should not be surprising that Biden emphasized in his November 7 victory speech that the work of his administration, “begins with getting COVID under control.” Between tackling the pandemic, revitalizing the economy, and addressing systemic racism and inequality in American society, there is a significant and momentous domestic agenda on the President-elect’s plate. Some observers may be left wondering whether the United States under a Biden administration will prioritize the challenges at home at the expense of challenges abroad. But Biden’s own worldview and the nature of his long record of public service makes this highly unlikely. The president-elect’s commitment to looking for global solutions to common issues is all the more important as the United States faces a changed and more difficult global landscape.

For those who may have seen domestic politics and foreign policy as existing in separate and distinct realms, the pandemic has revealed the inextricable link between them. The Trump administration’s “America First” approach to an inherently transnational issue was impotent in the face of the stark reality that—in addition to the coronavirus not respecting any sovereign borders—any nation’s ability to effectively respond to the virus is interdependent with the behavior of other states and therefore demands international cooperation and engagement. This is even more salient for the United States because the domestic economy rests on international financial and trading networks and, more specifically, the ability to mobilize a domestic response to the virus depends on capabilities that are nested within a complex global supply chain.

President-elect Biden clearly recognizes the connection between home and abroad. In his victory speech, Biden repeated what had become a mantra of his campaign; that, while the world watches America, the United States must, “lead not only by the example of our power, but by the power of our example.” Biden more explicitly emphasized the link between domestic politics and foreign policy in a recent article in Foreign Affairs, where he notes that his foreign policy agenda will begin at home: “First and foremost, we must repair and reinvigorate our own democracy, even as we strengthen the coalition of democracies that stand with us around the world. The United States’ ability to be a force for progress in the world and to mobilize collective action starts at home.” And, the President-elect has already stated that he will immediately reengage with the international community beginning in January, including rejoining the Paris Climate Agreement, reviving the Iran nuclear deal, and agreeing to a five-year extension of the New START nuclear arms control agreement with Russia.

The recognition that international engagement should not be sidelined even while grappling with urgent domestic challenges—indeed, that addressing the latter requires the former—should be expected given the arc of President-elect Biden’s career. Most will likely remember that, as vice president during the Obama administration, Biden played a significant leadership role in US foreign policy. But Biden also has a long history of personal experience in foreign affairs, organized around diplomatic engagement, that dates back to his early years as a junior senator on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee during the Cold War working on arms control agreements with the Soviet Union.

While engagement with the world and working with others will be vital for American foreign policy, at the same time it is essential to recognize that the United States faces a changing international environment. Most obviously, shifts in the distribution of power in the international system have continued (and, in some ways, accelerated) over the past several years. The United States is no longer in a position of unparalleled global hegemony that it had enjoyed since the end of the Cold War. These changes increase the stakes for American foreign policy because the United States cannot as easily absorb the costs of strategic blunders.

Beyond the distribution of power, there are several less-appreciated changes in what the international order actually looks like. In the absence of American leadership, traditional allies and partners have gone ahead and formed new relationships and agreements. After the Trump administration withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, eleven states comprising $10 trillion in total gross domestic product proceeded to sign a revised version of the agreement without the United States. And the European Union and Japan signed an EU-Japan Partnership Agreement to remove tariffs and other obstacles to free trade between them. At the same time, rival states have strengthened competing international institutions, such as through the enlargement of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization or the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank’s program to provide loans to states for coronavirus response efforts. They have also created alternative tracks within existing organizations, such as Russia’s creation of the Open-Ended Working Group within the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts as a separate track on cyber norms discussions; and they have taken the initiative to establish global standards in crucial areas, such as China’s announcement of China Standards 2035 to lead the development of international rules that regulate critical emerging technologies.

Taken together, these trends mean the United States cannot assume that other states will eagerly jump on the American bandwagon when there are alternatives to the provision of security and economic goods. Therefore, as the world becomes increasingly multipolar, American engagement with the world must be matched to a realistic appraisal of its relative power position, rather than shaped by nostalgia for a unipolar moment that has now passed. The United States risks strategic disintegration and dysfunction if its foreign policy and national security strategies are built on unworkable assumptions.

This should not—by any means—take away from a reinvigorated US foreign policy that takes seriously the importance of international engagement, diplomacy, and cooperation and the need both to reinforce and reshape international institutions to tackle the national security and economic challenges the United States faces. Rather, it is a call for realism and pragmatism about both the constraints and opportunities posed by an evolving international environment and the relative position of the United States within it.

Erica Borghard is a resident senior fellow with the New American Engagement Initiative at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and senior director on the US Cyberspace Solarium Commission.

Further reading:

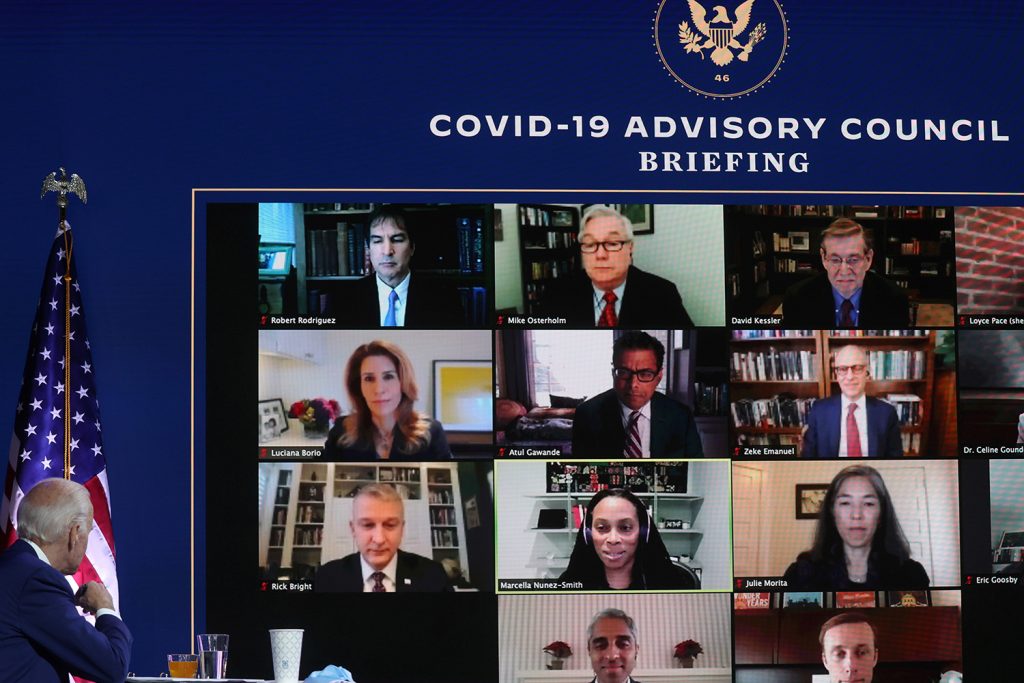

Image: US President-elect Joe Biden meets with members of the coronavirus disease "Transition COVID-19 Advisory Board" in Wilmington, Delaware, U.S., November 9, 2020. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst