The departure of former Bolivian President Evo Morales amid allegations of electoral fraud, coupled with political instability in several Latin American countries and the long-standing crisis in Venezuela, means that “the one constant in the region is uncertainty,” according to Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Morales resigned his post as president on November 10 following weeks of demonstrations over vote-counting irregularities during the presidential election on October 20 which saw Morales receive just enough votes to avoid a run-off election with former president Carlos Mesa. Following his resignation, Morales fled the country on a Mexican government plane to Mexico City, where he was granted asylum by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO).

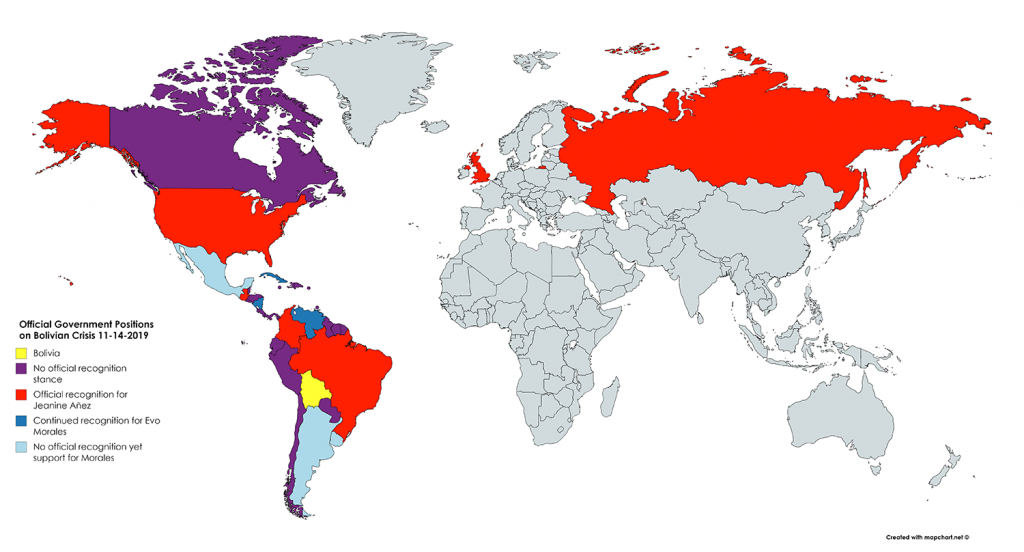

On November 13, opposition politician Jeanine Áñez was sworn in as the interim president during a session of Congress, despite deputies from Evo Morales’ Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) party boycotting the proceedings, prohibiting the chamber from achieving a quorum. Bolivia’s constitutional court ruled that Áñez is the legitimate interim president as the resignations of Morales and his top allies means that Áñez was the next-in-line for the job, without needing the legislature’s approval. The United States has recognized Áñez as the president, but the region and world remains divided.

The political turmoil in Bolivia comes as the region is also grappling with several other domestic political crises and an important transition in Argentina. Massive demonstrations in Chile and Ecuador have put pressure on political leaders to adopt new reforms and a national strike in Colombia is scheduled for November 21. Meanwhile, the President-elect Alberto Fernández of Argentina is already sparing with Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro weeks before Fernández’s inauguration on December 10.

On top of this, the region continues to struggle to find a way forward on restoring democracy to Venezuela, where Nicolás Maduro continues to hold onto power despite widespread international condemnation and a catastrophic economic and societal collapse.

Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center sat down with the New Atlanticist’s David A. Wemer to discuss the situation in Bolivia and the implications for the wider region. Here is an edited version of their conversation:

Wemer: Jeanine Áñez has been declared the interim president of Bolivia until new elections can take place. How is the region reacting to this and Morales’ resignation? Will countries recognize Áñez or continue to support Morales?

Marczak: The events in Bolivia have served to divide Latin America as to the impetus behind Morales’ departure and now whether Jeanine Áñez is the head of state. Until recently, the region was largely on the same page around the situation in Venezuela; bringing countries together across the spectrum and trying to confront the usurpation of power in Venezuela. Now we see the reverse playing out in Bolivia. Countries are debating why Evo Morales left power. Did he leave power of his own volition or was it a coup? There are two different responses to that question based on which country is speaking. Countries like Nicaragua, Uruguay, Mexico, and the Maduro regime in Venezuela have all come out saying this was a coup, and then others—Colombia, Peru, Brazil, the United States, and others—have said that there was electoral fraud.

This is factoring into what countries are recognizing Jeanine Áñez as the interim president. Evo Morales has tweeted from Mexico saying that she shouldn’t be recognized and Evo supporters say that they do not recognize her as the interim president. She was a relatively obscure politician up until just a couple of days ago. With this split on her recognition, there is now a second country in the region where the head of state is not uniformly recognized. This pretty significant and will play out beyond the region. Under the constitution, she must declare elections within ninety days. But the results of that election are likely to continue to inflame tensions among Evo’s supporters as both he and his vice president will be barred from running.

Unfortunately, this is a moment where external forces are seeing this as an opportunity to further put their stake in the ground and divide the region. Moscow has already blamed the opposition in Bolivia for violence and is likely seeking to further fan the flames.

Wemer: Where does MAS go from here? Will they continue to support Morales or will they take part in the new elections, perhaps with a new leader?

Marczak: The indications thus far are that MAS is unwilling to recognize Áñez as the interim president. If they are unwilling to recognize her, then the party will not likely recognize elections that she calls for.

There is an incredible divide in Bolivia between the traditional opposition strongholds in places like Santa Cruz and Evo’s strongholds of support. If MAS does not participate in the elections it will result in even greater chaos and violence. Whoever is the victor will not be recognized as such in the areas with a large MAS following. Bolivia is an already-divided country that risks further unraveling even with elections.

Wemer: The region is experiencing several different domestic political crises and a continued problem with Venezuela. How are the events in Bolivia impacting the wider region?

Marczak: The one constant in the region now is uncertainty. This is a shift from where we were a couple of years ago. Bolivia is only aggravating the ideological divide that is increasingly prominent across the region. We see extreme polarization across the world, but Latin America is now increasingly an example of what can happen when divisions are left unchecked. Beyond Bolivia, it’s concerning to see the growing rift between Argentine President-elect Alberto Fernández and Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who has repeatedly questioned the electoral choice of the Argentine people. The relationship between those two powerhouses in South America may further deteriorate unless we find points in common or bridges made between the two countries. That same polarization is playing out throughout the whole region.

I am also concerned about the role of foreign actors in helping to aggravate polarization, as well as regional actors. The more the region is divided, the more helpful it is to Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela. By using Bolivia to divide countries that have worked together to try to reclaim democracy In Venezuela, Maduro can prolong his usurpation of power. There are reports that elements affiliated and financed by Maduro also helped to fan the flames of the protests in Chile and Ecuador. I worry that Maduro could attempt to do something similar during the national strike in Colombia scheduled for November 21. For Nicolás Maduro, all of this is an opportunity for him to deflect attention from Venezuela, while also attempting to weaken presidents who have been outspoken in their support for the Venezuelan interim government.

Wemer: Will the events in Bolivia have any effect on the ongoing anti-government demonstrations in Chile?

Marczak: Chile was a surprise for everyone. Chile has always been seen as the star across the region. It used to be unfair to compare countries to Chile because it had higher growth rates and comparatively lower inequality. But what we have seen in Chile is that the subway rate hike was a catalyst for long simmering tensions in Chilean society that were frankly overlooked in the past. Chile is a wakeup call to the rest of the region that even though economic numbers might look good for a country, that doesn’t necessarily translate to the average person thinking their life is that much better. There were unrealistic expectations for how much better people thought their lives would become.

Chile also shows that we are in this new era of rapid communications, rapid mobilization, and political leaders have not responded to that. Many leaders have not recognized that the broader challenges across the region are inequality, the lack of trust in political parties, and the separation of the elite from the people. Piñera’s call to rewrite the constitution came quite late.

Leaders have also failed to communicate with the people in a way that actually resonates. Evo Morales came to power in 2006 as a cocalero [coca leaf grower] who was going to remake the country so that it was more responsive to the long simmering demands and gripes of the indigenous population. But once he was in power, he undermined institutional processes to keep running for office. There was growing resentment but also growing consolidation of power. This plays out throughout the region. It’s imperative that politics is not seen as a zero-sum game.

Wemer: Why did AMLO in Mexico give asylum to Morales? Will this decision have any effect on Mexico’s ties with other countries in the region or the United States?

Marczak: I was not surprised by Mexico’s decision to grant Evo Morales asylum because President López Obrador identified with Evo Morales. At the same time, Mexico has often tried to play a role of mediator in the region. Paraguay supposedly would have offered asylum as well but was not asked to make the offer.

The type of actions Evo Morales takes while in Mexico will determine possible backlash Mexico receives from this decision. If Evo uses his time in Mexico to rail against the United States and its allies in the region, that will become increasingly problematic for Mexico.

Wemer: What will Washington’s reaction be to the events in Bolivia? Will attempt to play any major role in resolving the crisis?

Marczak: There remains in Washington a very specific focus on resolution of the Venezuela crisis because the implications are frankly regional and global. Beyond the domestic implications, Maduro spreads crime and instability. Maduro sees developments in the region as an opportunity—a way to distract and divide.

So it is important to play a constructive role in Bolivia in tandem with our partners but not to the detriment of maintaining pressure and focus on Maduro’s exit in Venezuela. This means that we can expect statements and calls for peace but the Bolivia crisis is not one for Washington to resolve. We should be a partner in supporting countries that seek a return to the democratic order.

David A. Wemer is associate director, editorial at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

Further reading

Image: People protest against Bolivia's President Evo Morales in La Paz, Bolivia November 10, 2019. REUTERS/Marco Bello