On November 28, the US Treasury Department took an important step in responding to the SamSam ransomware cyberattacks, which occurred earlier this year. Considered one of the most effective cyberattacks in US history, the hackers behind SamSam since 2015 have targeted institutions ranging from companies to hospitals to schools, demanding payments in Bitcoin as ransom. After being paid, the hackers laundered these funds through online cryptocurrency exchanges into Iranian riyals, reaping the rewards of their malicious behavior. As part of their designation, the US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) included the Bitcoin addresses of Iran-based Ali Khorashadizadeh and Mohammed Ghorbaniyan, who are accused of assisting the hackers in laundering payments through online cryptocurrency exchanges.

Normally, OFAC sanctions designations include the name and other personal information of the target, but this is the first time that a Bitcoin address has been included. This is far from the first step that the United States has taken against actors in the cryptocurrency markets, but it is definitely one of the most powerful messages that Washington can send. These designations are a significant move and shatter the narrative that cryptocurrencies are invulnerable to US policy makers and designation authority.

This move, however, is not the first and will almost certainly not be the last one undertaken by the US Treasury to stem the emergence of illicit actors within cryptocurrency markets. In July 2017, US Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) pursued charges against Alexander Vinnik, a Russian national, and the Bulgarian cryptocurrency exchange, BTC-e, for allegedly laundering international payments, including ransomware proceeds from the landmark 2014 hacking of Mt. Gox. Prior to the designation, BTC-e had maintained a low profile relative to other Bitcoin exchanges, receiving more than $4 billion for its central role in criminal schemes ranging from drug trafficking to computer hacking and identity theft.

The crypto markets have already been preparing for these regulatory shifts. Though Bitcoin has dominated the popular narrative, so-called privacy coins offer significantly more anonymity. One of these coins, ZCash, features “Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-Interactive Argument of Knowledge” (zkSNARKS). While Bitcoin’s transactions link senders to receivers on a public blockchain, ZCash uses zkSNARKS to prove the validity of transactions, independent of addresses or other public information.

Another privacy coin, Monero, uses ring signatures to have multiple parties sign transactions, obfuscating attempts to link addresses to specific accounts. By using stealth addresses, only the sender and receiver in a Monero transaction are able to know where the specific amount was sent. These types of coins could frustrate future efforts to identify and target specific cryptocurrency addresses complicit with criminal or terrorist activities.

Cryptocurrency exchanges could also become the targets of reprisal activities. As demonstrated by the litany of calamitous hacks (Mt. Gox, Bitfinex, etc.), these exchanges could offer lucrative opportunities for terrorist groups and hacking networks. Further, these centralized exchanges could themselves be disrupted by decentralized exchanges (DEX), like WavesDEX, EtherDelta, or the Kyber Network. In contrast to centralized exchanges, DEXes are not owned by companies and are instead run on the blockchain, much like cryptocurrencies themselves. A DEX does not hold funds, positions, or transactions and instead serves as a matching layer for orders. DEXes have significantly lower levels of liquidity and transact exclusively in cryptocurrency, making them less attractive choices for ransomware hackers, but they could play an important role as middlemen within transactions, introducing tainted cryptocurrencies into otherwise clean exchanges. At the same time, the distributed structure of a DEX makes it immune to hacking attempts, given the absence of a central node within the underlying blockchain.

Though these are formidable challenges, cryptocurrency is not the first decentralized financial network that US policy makers have had to address. Well before 9/11, different terrorist groups started using informal money transfer networks to move funds making it difficult for US authorities to detect. Moving forward, it will be critically important to continue to leverage technical expertise and operational creativity, to disrupt these informal financial networks for illicit activity, which could be utilized through a similar presence in cyberspace.

Michael B. Greenwald is senior adviser to Atlantic Council President and Chief Executive Officer Frederick Kempe. He is a fellow at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center. From 2015-2017, he served as the US Treasury attaché to Qatar and Kuwait. He previously held counterterrorism and intelligence roles for the US government.

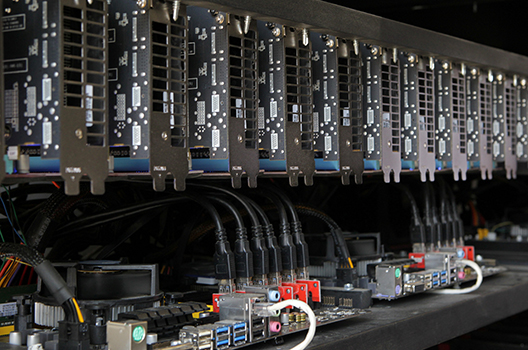

Image: Cryptocurrency mining facilities are seen in Pristina, Kosovo June 12, 2018. Picture taken June 12, 2018. (REUTERS/Hazir Reka/File Photo)