In a move anticipated for weeks by Western governments, China’s National Security Law has now taken effect in Hong Kong and will push the transatlantic community to back up its rhetoric defending Hong Kong freedoms. While the European Union and its members have issued statements in defense of Hong Kong’s sovereignty and hinted at consequences, the UK parliament hotly debated use of its post-Brexit autonomous sanctions while promising to issue passports to Hong Kong residents. Legislators in Europe are accusing their ministries of slow roll. But Washington is mounting a regulatory onslaught in response to China’s transgressions with no defined trajectory. The coming weeks will be a test whether US actions will send a clear message, or whether we’ll have a China shake-and-bake.

“Shake and Bake” is the eponym for a lab science class at undergraduate institutions designed for those who shouldn’t be wearing lab goggles to save themselves but are fulfilling a graduation requirement. “Volcanos, earthquakes, and other natural disasters” promised my course guide—it was interesting and unpredictable. My main takeaway at age twenty was that there are warning signs, but they rarely come early enough. It is unclear how different variables will interact, and which combination could lead to calamity.

On July 2, the House of Representatives passed the “Hong Kong Autonomy Bill,” a generously worded piece of legislation that calls for but does not mandate sanctions as recent bills have, notably on Russia. Some parts of the executive will be relieved not to see their policy bound by Congress this time around, but others would have welcomed stronger language that backed Treasury into a more aggressive corner. This dynamic will be familiar to all those observing or directly impacted by the tug of war between two co-equal branches asserting co-equal claims on one of the United States’ most powerful policy tools. In good timing, the Commerce Department tightened its grip on the export of weapons to Hong Kong, citing the security law as proof that one could no longer draw a distinction between Hong Kong and mainland China. After all, local police could use these in the crackdown.

Interestingly, the US administration also chose this particular moment to increase pressure on Beijing in response to human right abuses in Xinjang through a mix of economic and law enforcement measures (in the illicit financial space, these two work hand-in-hand). State, Treasury, Commerce, and Homeland Security issued a supply chain advisory, warning US firms to monitor for potential trade partners making ill-gotten gains from Xinjang labor camps. Making this case very real, the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection seized a shipment at Newark Airport of human hair weaves, presumed to be sourced from the camps themselves. And US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo promised sanctions for human rights abuses, which could be achieved through existing Magnitsky authority without the extra push from the Hill. After all, Magnitsky is specifically designed to target individuals whose illicit wealth and corruption have undermined democratic values and human rights. Could the United States also apply this authority to those punishing protestors in Hong Kong?

From this perspective, Xinjang measures are a toe in the water. The case is in line with previous US efforts to impose non-military (and therefore “low risk”) consequences on democracy violators on the other side of the world. But the Hong Kong question potentially threatens global financial stability. Let’s recall that in 2014, the US government and European partners hotly debated sectoral sanctions that would punish sectors of the Russian economy for incursions in Ukraine. Knowing how dependent Moscow was on Western capital markets, the central question for the United States was: how do we impose debt and equity restrictions on a global economy? The answer was to limit their maturity—Russia could still raise short-term debt and US policy wouldn’t risk precooking a default. Russia had been there in 1998. It wasn’t pretty, and that was before its accession to the World Trade Organization.

With Hong Kong, US regulatory bodies seem willing to move into uncharted territory and test market stability. The President’s Working Group on Capital Markets, an interagency body of regulators led by the Treasury, has vowed to examine potential restrictions on Chinese firms’ access to US stock markets in response to the Hong Kong Security Law. It is set to issue recommendations by the end of this month. These are dangerous waters, because it’s hard to quantify the value of Hong Kong for the United States. It is the financial portal for the West to Asia, the hub of banking giants like HSBC and countless US and Western businesses, and foreign institutions based there finance vital supply chains for the US economy. It is frightening to imagine the magnifying effect of pursuing this tactic at a time when COVID has wreaked havoc on global growth. There appear to be too many variables at play to model.

And let’s not forget the Defense Department in this brew—after all, our “China problem” is a paradigm of the intersection between national security and economic policy. On June 24, the Pentagon submitted a list of Chinese firms that posed a national security risk due to their association with the Chinese military. Several of these are publicly traded in New York. But this submission was in response to a longstanding Congressional requirement dating to 1999 and its deliberations occurred in a separate silo (more aligned with the 5G and broader technology debate—Huawei is on the list) than the current process led by the Treasury. This is a situation where the government’s operational silos might become a cumulative risk to the greater good.

The US foreign policy engine oiling its gears can be an exciting thing when we get it right, but it appears we’re about to suffer from both a messaging and sequencing problem, opening a pandora’s box with novel financial tools that cannot be closed, especially if China hardens is line. What doesn’t help is the administration’s polarized trade policy, with advisors ranging from defenders of free market enterprise to those advocating a modified return to autarky, each making his case. And Phase one of the China trade deal still lives.

It is unclear how we will sequence these measures and account for myriad externalities to global markets while keeping pace with the political prerogative. It is equally unclear whether we can mix and match measures we take in response to Xinjang and in Hong Kong. Hardliners will argue this is a false, academic distinction in the face of an authoritarian regime that may not draw such a distinction itself, while technocrat practitioners might say this approach undermines a clear carrot and stick incentive structure to compel China to change its behavior.

These camps are hashing out their differences in real time with different conceptions of “no return.” In “shake and bake,” you learn that the world is full of dependent variables. The risk is a policy outcome achieved by accident and not by design.

Julia Friedlander is the C. Boyden Gray senior fellow and deputy director of the Global Business and Economics Program at the Atlantic Council. She has served as senior policy advisor for Europe at the US Treasury and director for European Union, Southern Europe, and Economic Affairs at the National Security Council from 2017 to 2019.

Further reading:

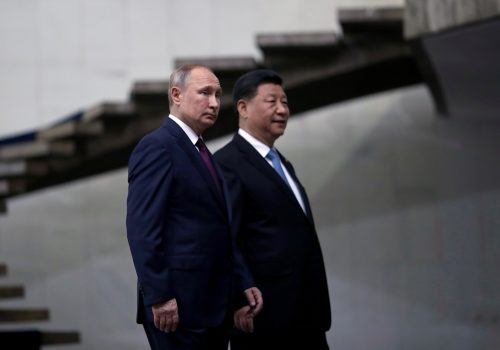

Image: US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo speaks during a news conference at the State Department in Washington, US, July 1, 2020. Manuel Balce Ceneta/Pool via REUTERS