With the United States bogged down by economic troubles at home, wriggling to organize its departure from Afghanistan and grappling with a variety of crises in the Middle East, it comes as no surprise that China is using the opportunity to invest considerable time and money into reviving the so-called Silk Road.

The concept of rejuvenating the Silk Road route that would, among other things, give a boost to Afghanistan’s struggling economy, has been paraded around for years by the U.S. State Department. Yet little actual progress has been made aside from ensuring the construction of reliable routes out of Afghanistan. Rather than pervasive regional economic development, the U.S. has spent its resources solidifying the longer, albeit more stable, land route out of the war zone through Central Asia. The effort, however necessary for the United States in a military sense, is hardly a substitute for broader economic investment and development in Central Asia.

Although American multinational companies such as Hewlett-Packard have pioneered using railroad routes through the region to bring electronics manufactured in China to Europe, the trains are Chinese, the drivers are Chinese and China garners significant benefit from the arrangement.

U.S. political relations with Central Asia are narrow, related almost entirely to the war in Afghanistan and the global wars on terrorism and drugs. Central Asia is on the other side of the world and its markets present little established opportunity for American businesses.

The United States exports very little to Central Asia and the region sends very little across the globe to North America. Even Kyrgyzstan, where the U.S. has maintained an air base for the past decade, sends only .13 percent of its total exports to the United States, and the U.S. accounts for only .56 percent of Kyrgyz imports. Additionally, Central Asia’s governments hardly fit into idyllic American desires for a free and open world. The gains to be had from intense U.S. involvement in the region are few, the potential costs great — in economic terms, especially — and the political motivation nonexistent.

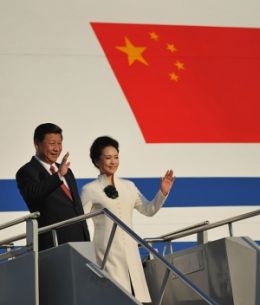

No U.S. president has visited the former Soviet states of Central Asia; by contrast, three consecutive Chinese presidents have. President Xi Jinping’s early September tour of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan highlighted that China plans on seizing what Xi called “a golden opportunity” for development. Traveling throughout the region before attending the 2013 Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit in Kyrgyzstan, Xi made multiple well-received speeches and finalized numerous deals. Among the most notable was a package of agreements signed with Kazakhstan worth $30 billion, primarily relating to energy projects.

Xi’s successful tour underlined the Chinese government’s determination to deepen ties with Central Asia, and geographic proximity certainly gives it an edge over the United States. “A near neighbor is better than a distant relative,” Xi said of Central Asia and China during his September 8 speech in Astana, Kazakhstan. As he went on to argue, “Our 1,700-kilometer long common border, two millennia of interactions and extensive common interests not only bind us closely together, but also promise a broad prospect for bilateral ties and mutually beneficial cooperation.”

China is also not burdened by the ideological commitment to fostering free societies, which weighs on the United States. Although the exigencies of the war in Afghanistan have dictated a light hand toward Central Asia’s despots, the region’s poor human rights record will continue to be an obstacle to developing more wide-ranging ties with the United States. China, on the other hand, is free to deal with the despots of Central Asia based solely on geopolitical and economic terms. Chinese investment comes without the burden of moral judgment, and is of direct and immediate profit to businesspeople and government officials from Astana to Beijing.

Chinese efforts to revive the Silk Road will undoubtedly be more successful in the short term than American initiatives. But if and when Central Asia’s citizens experience an awaking similar to that of the Middle East, this time China will be the regional power caught up in the conflagration.

Catherine Putz is a digital communications assistant at the Atlantic Council and a graduate of the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky.