“There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen,” said Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov—better known as Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin—during his exile prior to the 1917 Revolution. Today though, the quote describes what Europeans and others in the world are experiencing. The abruptness of the change the world is witnessing—which happened, quite literally, overnight—in conjunction with the violence in Ukraine relayed by the media, generates deep uneasiness and fear. How will this affect the rest of the world?

Beyond this question, we Europeans in particular must ask ourselves why the bombing of Mariupol has been so shocking, when we watched—unperturbed—the atrocities Russian President Vladimir Putin committed in the Chechen capital Grozny in 1999-2000 and in Aleppo, Syria, in 2016.

We look to history for an answer: There are events that act as catalysts for situations in suspension. They mark a before and an after, crystallizing the evolution. The Russian invasion of Ukraine seems to belong to that terrible category. We are entering times of collective unrest: Globalization, as we understand it, has ended, and international relations are already disconnected from what has come to be considered established practice. And all signs indicate that multilateralism will undergo a profound transformation.

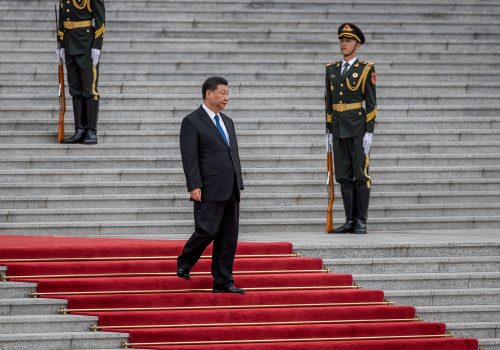

Although it was Putin who triggered this shift, it is China whose protagonism will be defining. That protagonism was on full display when US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan met with Chinese diplomat Yang Jiechi on Monday.

Without drawing attention away from Ukraine, it is of utmost importance to consider Chinese President Xi Jinping’s strategies, specifically with regard to three areas of interest: the contortion of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership in relation to its Westphalian foreign policy; the interplay between China’s actions and its vision of an alternative international order; and the alterations to the great economic-political designs of Xi (with his aspirations of lifelong service, like his Russian friend).

Western intelligence maintains that Beijing had, at the very least, inklings of Putin’s machinations of war—a fact which makes China’s mixed messaging even more striking and denotes a turning point in its position on non-interference in the internal affairs of other sovereign nations.

This shift in thinking was made explicit in the joint statement from February 4, the culmination of a Putin-Xi bilateral meeting. It is worth mentioning that the version published on the Kremlin’s website is more than five thousand words long, unlike the Chinese foreign ministry’s “summary” (four times shorter), which tiptoes around—or avoids entirely—certain hot-button topics (NATO, for one). The timeline is also important: The statement was released twenty days before the beginning of the attack on Ukraine which, in turn, started just after the conclusion of the Beijing Olympics. A moment chosen, according to US sources—who, in this matter, have proven exemplary—to appease the Chinese president.

Putin and Xi’s friendship with “no limits” was recorded by the aforementioned document and has since been echoed (and replayed on loop) by government spokespeople. One wonders what led Xi to opt for this level of a commitment to Putin: How much was Xi influenced by the consensus regarding Russian military superiority that was expected to be reflected in a speedy and efficient takeover of Ukraine? How much weight did Xi give to the supposition that the operation would not have a significant impact on his economy (along with the very Chinese principle of seeing opportunities in every crisis—such as the ability to buy large stakes in Russian oil and gas companies that the Chinese government is reportedly evaluating)? How absorbed was Xi by the notion that a decadent Europe—the whole West—would get caught up in grandiose declarations and do little more?

China, in its support for Russia and its historical defense of national sovereignty, is on a tightrope. And, caught in an impossible balancing act, it is trying to play several hands at the same time. Beijing abstained from voting for the United Nations General Assembly resolution against the Russian invasion (as it did in the UN Security Council’s similar proposal, struck down by a Russian veto). But last Monday, China offered to mediate “when needed”—as if the need were not already excruciating. In parallel, China has committed almost $800,000 in humanitarian aid to Ukraine, lamenting civilian casualties and imploring “restraint,” as well as refusing to provide replacement aircraft parts to Moscow (for now). All this while underlining its alliance with Russia as “one of the most crucial bilateral relations in the world.”

Xi’s contradictions stem from his defense of the Kremlin’s “reasonable security concerns”—to this day, he has avoided designating Russian actions in Ukraine as an “invasion.” On March 7, Foreign Minister Wang Yi again underlined China’s commitment to its “ever-lasting friendship and mutually beneficial cooperation” with Russia, which is founded on the “clear logic of history.” In this string of cartwheels and pirouettes, Wang continues on to say that China believes it must “respect and protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries.”

Of special importance in the Russian version of the aforementioned joint pronouncement (not the “synthesis” produced by the CCP) is the condemnation of NATO enlargement. China, until now, had avoided taking sides. In this context, we are already seeing ramifications of the war in Ukraine: It has breathed new life—renewed the raison d’être—of NATO, generated unprecedented European unanimity, and strengthened both the transatlantic link and the image of gravitas that the United States left behind in Afghanistan. Ramifications which, paradoxically, run counter to Xi’s foreign-policy interests.

There is agreement regarding the nature of the China-Russia relationship, considering their tumultuous shared historical heritage: It has been dubbed a marriage of convenience, something temporary. The truth is that, even beyond past tensions, the two make an unlikely duo. China, an economic giant with bullish growth projections, has been striving to wield the soft power it has worked so hard to build (with little to no return on investment). Russia, the epitome of revanchism, is a declining spoiler state seeking to regain former greatness by brandishing its nuclear-armed military capabilities.

Moreover, Beijing has benefited from the global order cemented after World War II, specifically from the economic, military, and geopolitical stability the order provided. China learned to adeptly navigate Cold War dynamics and, since the United States’ Nixon administration, international institutions—over time, Beijing’s end goal became remaking the system in its image. Moscow, on the other hand, has rooted its actions firmly in historical victimization, claiming damages for the alleged contempt inflicted by the liberal system, which it seeks to undermine.

Added to this is the unexpected, powerful response of the international community to the invasion of Ukraine in terms of attitude, reprisals, and sanctions. The dominos have started to fall toward China: A week ago, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang announced China’s lowest annual growth target (5.5 percent) since 1991. The potential for an internal crisis stemming from faltering economic development—the sole clause in Xi’s “social contract” with his citizens—is of concern to the president. It should not be forgotten that China’s trade with Russia, a lifeline for Putin, represents less than a fifth of its trade with Europe.

The growing toxicity of the China-Russia relationship is incontrovertible. It weighs down the public image that Xi, unlike Putin, has carefully sculpted, recognizing its correlation to soft power. In cozying up to Russia, Beijing shares the stage with countries like North Korea, Syria, and Belarus, which makes it difficult to sell itself as an alternative hegemonic leader.

In the end, Xi’s geopolitical juggling has profound implications for his number one priority: the future of Taiwan. China cannot help but notice the translatability of Ukrainian courage to Taiwan.

China’s support for Russia hardly squares with the cornerstones of Xi’s leadership: the use of state capitalism as a gravitational field to attract others into China’s orbit, respect for national sovereignty, and peaceful emergence into world leadership.

For the moment, the West is winning the information war; it should not lose sight of this. But Europe must pay close attention (as should the rest of the world) to China’s oscillations, compromises, manipulations, and back-room alliances. It is proving to be an unreliable interlocutor. For this reason, the European Union “third way” mentality—with Germany at the helm—to maintain equal distance from the United States and China is not feasible.

The world is becoming more uncertain. Negotiating with Beijing will be necessary. Europe should do so with eyes wide open, with the full use of its toolkit. To do so, it must overcome internal cliques and divisions, prioritize NATO, and move beyond the formats of the past. Now, more than ever, it is essential for Europe to fully bring in the Baltics, Poland, NATO’s southern flank, and, to paraphrase former German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, coordinate with its American friend. In today’s world, as in the one to come, there is no place for Europe to be equidistant between the United States and China.

A version of this article originally appeared in El Mundo. It has been translated from Spanish by the staff of Palacio y Asociados and is reprinted here with the author’s and publisher’s permission.

Ana Palacio is a former minister of foreign affairs of Spain and former senior vice president and general counsel of the World Bank Group. She is also a visiting professor at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and a member of the Atlantic Council’s Board of Directors.

Further reading

Tue, Mar 15, 2022

FAST THINKING: What China stands to gain—and lose—by wading into the Ukraine war

Fast Thinking By

How far will these autocrats take their “no limits” friendship?

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

Thu, Feb 10, 2022

What will China do if Russia escalates in Ukraine?

New Atlanticist By Katherine Golden

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd and former US National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley tackled the big questions about the China-Russia partnership at an Atlantic Council event.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin attend a ceremony dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Russia and China, in Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, Russia on June 5, 2019. Photo by Sergei Ilnitsky/Pool via Reuters