On May 15, Costa Rican President Carlos Alvarado announced that the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) had formally invited Costa Rica to become its thirty-eighth member—a milestone for the small Central American nation which consistently outperforms its peers in many international rankings, especially in environmental and social indicators. As an OECD member country, Costa Rica will have to comply with the highest standards across policy areas as it continues to open up the country to competition, while grappling with the economic consequences of COVID-19.

The road to the OECD began in 2013 when President Laura Chinchilla’s administration formally expressed interest in membership. The OECD espouses pro-market policies and seeks to foster global trade. Its member countries currently represent eighty percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) and sixty percent of global trade. With this invitation, Costa Rica is the first country in Central America to secure membership and the fourth in Latin America after Mexico, Chile, and Colombia.

As part of the formal adhesion program, negotiations and rigorous evaluation from the OECD started in 2015. Costa Rica was evaluated by twenty-two technical committees—ranging from fisheries to digital commerce to competitiveness. The committees drafted Costa Rica-specific requirements as well as recommendations that would better allow the country to achieve inclusive economic growth, fiscal and macroeconomic stability, and improve its competitiveness. To date, Costa Rica has passed fourteen new laws or administrative reforms in response to OECD recommendations.

Given the historical lack of competition and monopolistic practices in Central America, one of the most important reforms for Costa Rica was the passage of the Competition Authority Strengthening Law (Ley de Fortalecimiento de las Autoridades de Competencia) in September 2019. While Costa Rica is the most competitive nation in Central America and the fifth most competitive in Latin America, it fell seven spots in last year’s World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness ranking. In fact, only two thirds of economic sectors have sufficient competition, although OECD best practices should help change this. In the long term, an opening of key sectors—which will be hard politically—will help encourage investment and ameliorate the business climate. Currently, in comparison with its OECD peers, Costa Rica will only surpass the competitiveness level of Turkey. Without free competition and choices for consumers in electricity, sugar, and rice, to name a few examples, Costa Rica will continue to be the most expensive country in Central America, and one of the most expensive in Latin America.

It is hardly contested that Costa Rica’s accession to the OECD will allow the country’s economy to become more dynamic and diversified as it adopts the organization’s standards and becomes more competitive. The OECD “seal of approval” and emphasis on rule of law and strong governance will help Costa Rica attract new sources of foreign direct investment.

But accession to the OECD is not the end of the road for Costa Rican development. Many of Latin America’s structural issues are also very present in Costa Rica—high inequality, high informality, and unemployment, and low productivity and tax revenue collection combined with unfettered public spending. These will be exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. While Costa Rica will likely rank in the lowest OECD rungs for the foreseeable future, this accomplishment demonstrates that the country is capable of working together—across three administrations and through numerous bills—towards a shared goal for the country’s well-being and much-needed continued improvement.

Maria Fernanda Perez Arguello is an associate director with the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, where she focuses on Central America, Mexico, and the USMCA.

Further reading:

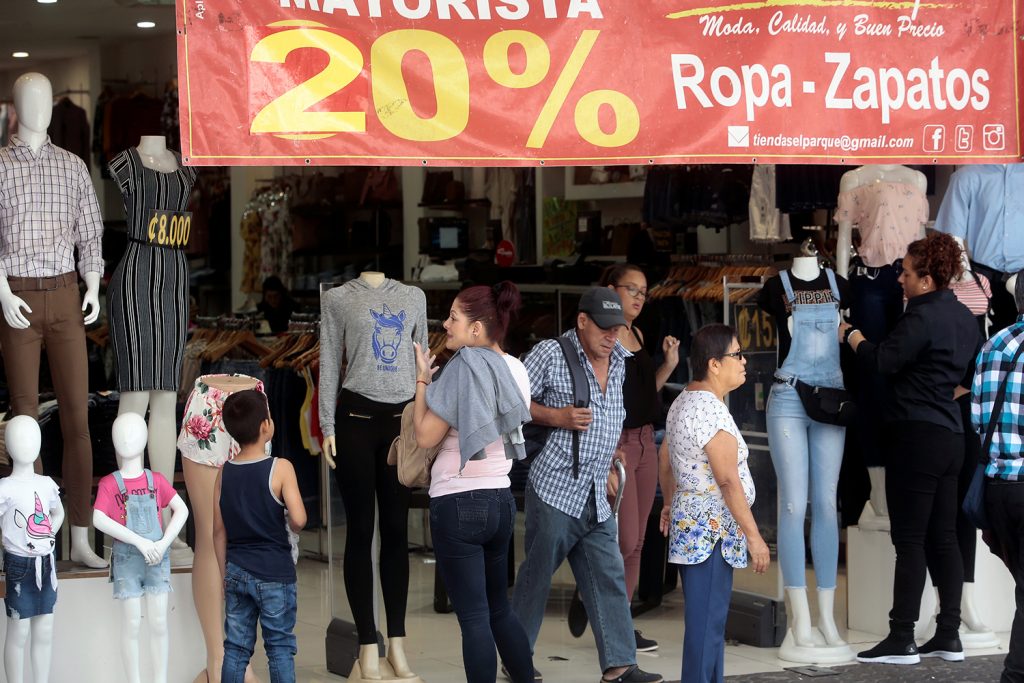

Image: People walk by a store on Central Avenue in San Jose, Costa Rica March 13, 2019. REUTERS/Juan Carlos Ulate