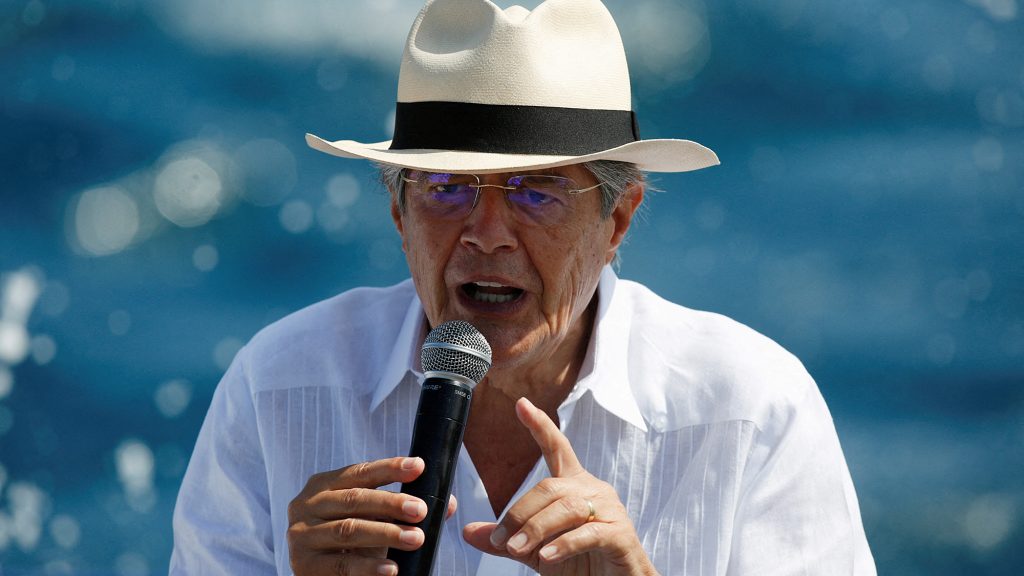

While all eyes were on the athletes competing in the Winter Olympics in Beijing last month, China was busy staging high-level international convenings behind the scenes. Chinese President Xi Jinping welcomed the leaders of Argentina and Ecuador, underscoring China’s growing influence in Latin America. That influence was solidified as Buenos Aires signed a memorandum of understanding on China’s Belt and Road Initiative. But Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso’s dealings in China highlighted just how important it will be for the United States to nurture its ties with governments that have shown an interest in cooperating with Washington.

Lasso reaffirmed Ecuador’s commitment to cooperating with Washington when US Secretary of State Antony Blinken traveled to Quito in October 2021. While meeting with Lasso, Blinken hailed the Ecuadorian president’s work toward combating corruption, an area of mutual interest between the United States and Ecuador. And the two countries committed to continuing to work together on upholding democratic governance and values globally as well as on drug trafficking and climate change.

But a couple of topics discussed at Lasso’s visit to China (beyond the widely reported possibility of a free trade agreement or the restructuring of Quito’s debt to Beijing) raise concerns about Quito’s willingness to push back against problematic aspects of its ties with Beijing. Those topics include the expansion of Chinese surveillance technology and the negative social and environmental impacts of some Chinese projects in Ecuador.

The joint statement that followed the Xi-Lasso meeting mentions that Ecuador “positively commented” on China’s Global Data Security Initiative, Beijing’s response to a Trump administration initiative called Clean Network that sought to curb the use of information and network technology, and prevent surveillance or intrusion, from China. The new statement is concerning because Ecuador had previously agreed to be part of the Clean Network. Lasso also held meetings with various Chinese enterprises about commercial opportunities in Ecuador that should similarly raise concerns in Washington about Quito’s willingness to break from the United States on issues of mutual interest.

Activities surrounding Chinese investments in Ecuador—and their negative impacts on the country—raise further questions about Quito’s willingness to push back against Beijing. According to Ecuadorian press, several Chinese companies met virtually with Ecuadorian authorities to talk about investments including Huawei, ZTE, China Electronics Corporation (CEC), and PowerChina. PowerChina is the parent company of the Sinohydro Corporation, which built the controversial and faulty Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric plant. The dam reportedly displaced more than one million people and destroyed forests. The state-owned Corporación Eléctrica del Ecuador has entered commercial arbitration with Sinohydro through the International Chamber of Commerce to resolve mechanical problems with the plant. Despite all of this, Lasso reiterated to Chinese business leaders, including PowerChina, the opportunities that Ecuador offers as an investment destination. He publicly stated to Chinese businessmen that he will have an international auction for the Corporación Nacional de Telecomunicaciones, Ecuador’s public telecommunications company, and sell the Banco del Pacifico to a foreign bank. China National Petroleum Corporation was also among the enterprises that met with Lasso, despite the fact that the Ecuadorian National Assembly has been investigating one of the corporation’s arms—PetroChina—and its oil-for-loan deals with Ecuador, which the president of the National Assembly Audit Commission called “the largest oil corruption plot in Ecuador.”

Similarly, Chinese companies including the China National Electronics Import and Export Corporation (CEIEC), a CEC subsidiary, and Huawei were involved in the controversial ECU-911 surveillance system in Ecuador. CEC and Huawei have both been sanctioned by Washington, and CEIEC has also been sanctioned for aiding Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro’s efforts to surveil political opponents and restrict internet service. ZTE, also sanctioned by the United States, helped develop Venezuela’s “fatherland card,” allowing the Maduro regime to monitor Venezuelans’ activities, including how they vote.

All of this is not to say that Washington should be discouraged about the possibility of deepening ties with Ecuador. In fact, Washington has a unique opportunity with Lasso to deepen ties and cooperation that restarted during the preceding Moreno administration. Certain aspects of Chinese cooperation with Ecuador run counter to—and therefore are likely to hinder—US-Ecuador cooperation. Thus, Washington cannot take for granted the opportunity it has now under Lasso, and it must actively compete with China if it wants to advance collaboration on mutual interests with Ecuador.

Washington should raise its concerns to Quito. Such US efforts in the past have been successful in Latin America, like when US Southern Command raised concerns over Chinese investment in deepwater ports and infrastructure on the Panama Canal and whether these projects could allow the Chinese military to gain a foothold around a critical global shipping lane. Panamanian President Laurentino Cortizo is credited with adopting caution following these US concerns.

Washington must also come prepared with alternatives including economic deals in key sectors—infrastructure investment is already being explored in Panama—that promote transparency, more readily account for and prevent social and environmental impacts, and respect democratic values and human rights. Beyond economic cooperation, the United States and Ecuador must continually nurture their collaboration on advancing their democratic and security interests. Washington cannot risk dulling its engagement in the region and should pay particular mind to those governments that would prefer cooperating with the United States instead of China.

Gabriel “Gabo” Alvarado is a nonresident senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub with previous experience at the US Department of State in the bureaus of East Asian and Pacific Affairs and Western Hemisphere Affairs.

Further reading

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

US-China vaccine diplomacy: Lessons from Latin America and the Caribbean

Report By

The implications of diverging COVID-19 responses, notably at the onset of the pandemic’s rise in the region, will reverberate beyond the health sector. What might the differing US and China pandemic approaches portend for future influence in the region?

Sun, Feb 6, 2022

The world’s top two authoritarians have teamed up. The US should be on alert.

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

It would be a profound mistake to see the Ukraine crisis in isolation at a time when Xi and Putin have provided its disturbing context.

Wed, Dec 8, 2021

Democracy in Latin America is under threat. These two summits are a chance to fix it.

New Atlanticist By

As nations across the Americas come together to address their shared shortcomings, here's a roadmap to help bolster their democratic institutions.

Image: Ecuadorian President Guillermo Lasso speaks at the inauguration of an extended marine reserve that will encompass 198,000 square kilometers (76,448 square miles), aboard a research vessel off Santa Cruz Island, in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador on January 14, 2022. Photo via REUTERS/Santiago Arcos.