The tectonic plates are shifting. The European Parliament elections, which wrapped up Sunday, saw the centrist coalition remain in power—but far-right forces make striking, if uneven, gains across the continent. The epicenter of the political earthquake was France, where Marine Le Pen’s National Rally party had double the support of President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance—leading Macron to call for snap elections in the coming weeks. Below, our experts take stock of the results across Europe.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Jörn Fleck: The right is rising, but don’t expect a revolution

Dave Keating: Could a ‘supergroup’ unite the far right?

Daniel Fried: The center held, but just barely

Paolo Messa: Will Giorgia Meloni be the new Angela Merkel?

Nicholas O’Connell: Italian influence across European institutions is growing

Aaron Korewa: In Poland, the prime minister is strengthened but his coalition partners are weakened

Andrew Bernard: In Portugal, the pendulum swings back to the socialists, while Chega underperforms

Carol Schaeffer: In Germany, a new AfD challenger is emerging—is it leftist or right-wing?

Patrik Martínek: The Czech political landscape remains highly fragmented

The right is rising, but don’t expect a revolution

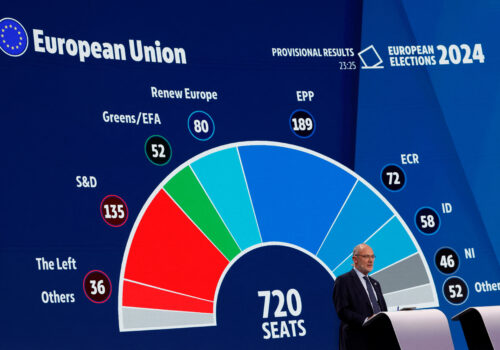

Initial results and exit polls suggest few surprises from the outcome of the European elections: The next European Parliament will see a shift to the right, with the mainstream center-right European People’s Party (EPP) placing first and parties from the far right making modest gains. Voters punished green and liberal parties, and to a lesser degree center-left social democrats. Even if important differences and idiosyncrasies among member state results remain, all that was largely expected.

But what impact exactly this shift to the right will have on the future of the European Union, its politics, and its key policies is far less clear on election night. Expect more complexity and protraction, but hardly a revolution in parliamentary business.

At the strategic level, the key question is whether the political right can overcome disunity and wield its supposed new power. Far right, hardcore Euroskeptic parties are dispersed across at least two political groups and the nonaligned. Divisions among these parties—especially among two of the largest players in this ill-defined bloc, the French National Rally (NR) and the German Alternative for Germany (AfD)—have in the past prevented concerted political action in the parliament and have recently flared up again. Add to that the unresolved relationship between the two more mainstream conservative forces—the EPP and the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), which includes Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy and the Polish Law and Justice party—and between them and the far-right bloc, and it’s far from certain the political right can really act in unison in parliament to leave a significant imprint on policies from the green transition to migration and economic competitiveness.

Two other factors will likely moderate the impact of this shift to the right. For one, in absolute terms, mainstream pro-EU parties will retain a solid, if shrunken, majority of 450-plus seats (out of 720). The small rightward shift in the center of gravity of that “mainstream coalition” will help the EPP little in shaping conservative policies if it cannot threaten the center-left parties with a credible alternative majority on the right, especially from the ECR. Second, the European Parliament does not possess the right of initiative. All EU legislation originates from the EU’s executive, the European Commission, and the European Parliament is a mere co-legislator in the process, together with the Council representing the twenty-seven member states. In that role, the Parliament can try to block, delay, and amend legislation. But it will hardly reshape the strategic direction of EU policies.

The election outcome does mean more uncertainty for a second term of current Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. This is less because the mainstream coalition of pro-European parties in the new Parliament does not have a solid majority that could get von der Leyen over the finish line. Rather, it is because of the wild-card element of Macron calling national parliamentary elections following the thumping his party coalition received in the European ballot at the hands of the nationalist, Euroskeptic National Rally. The snap elections between the end of June and mid-July broadly coincide with the period for EU leaders and the new European Parliament to have finalized the nomination and confirmation of the next Commission president. It seems unlikely that Macron, at the helm of the second largest EU member state, will drive forward that process before this do-or-die campaign for his party and legacy is settled. And a National Rally victory in this Macronian gamble of a ballot carries institutional implications for the EU. Much will depend on developments in France and on how much certainty, consensus, and stability European leaders can project at their upcoming summits in mid and late June.

—Jörn Fleck is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

With his snap elections gamble, Macron may be trying to discredit National Rally’s governing ability

Macron’s party suffered a huge setback in the European Parliament, securing only 14.5 percent of French ballots, well behind the far-right National Rally, which won with 31.5 percent of the vote. On the same day, Macron dissolved the National Assembly, marking the first time a French president has done so since 1997, and called for new legislative elections that will take place on June 30 and July 7. Since his reelection in 2022, Macron has, with difficulty, governed with a relative majority in the National Assembly, despite a recent reshuffle that welcomed a more right-leaning government. The snap elections put Macron’s Renaissance party in a duel with the National Rally, with the aim to present his party and policies as the only possible barrier to far-right populism.

It’s a risky endeavor to bet that far-right parties will not gain a majority in the National Assembly. This is purely political maneuvering from Macron, as there are no institutional rules that call for such a decision. If National Rally were to win a majority of seats in the National Assembly, this would lead to the creation of a “cohabitation” government, with Jordan Bardella or Le Pen potentially becoming prime minister. Perhaps by calling for snap elections, Macron is making the risky bet that if the National Rally does win enough seats to join the government, the party can then be discredited and pushed out of power before the 2027 presidential elections.

Le Pen’s party has been extremely critical of Macron’s policy toward Russia, opposing “useless” sanctions at the outset of the war as well as every new initiative to support Ukraine over the past few months. The Kremlin has exploited these narratives to support Russia’s war of aggression. The repercussions of the potential arrival of the National Rally party in government can however be tempered by the institutional set-up of the Fifth Republic. In times of divided government, the president can carve out a “reserved domain” (“domaine réservé”) for foreign and defense policy, and Ukraine would logically fall into that category.

—Léonie Allard is a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center, previously serving at the French Ministry of Armed Forces.

Could a ‘supergroup’ unite the far right?

The big news of Sunday night was the shock decision by Macron to dissolve the French parliament and call a snap legislative election in response to the astonishing performance of Le Pen’s far-right National Rally party, which received more than twice the votes of Macron’s party. But it’s important to note that this far-right surge in France did not occur in the EU election as a whole.

According to the latest projections, the far-right ECR group of Giorgia Meloni will go from 9.5 percent to 10 percent of the seats, while the far-right Identity and Democracy (ID) group of Le Pen will actually shrink from 8.2 percent of the seats to 8.1 percent. That’s because Le Pen kicked the German far-right party AfD, which came second in its country, out of the ID group just before the election (with AfD included, ID would have increased its share by more than ECR did). So what we know already is that there was no far-right surge overall, and in fact the gains were in line with the trajectory of the far right’s growth over the past two decades. But now comes the group formation process, in which many of the new undeclared or nonaligned members of the European Parliament are likely to join ECR and ID, which may unite into a far-right supergroup if Le Pen has her way. But even if they do, they would not have enough members to tempt the center-right EPP into a right-wing majority coalition. The EPP emerged the big winner of the 2024 election, just like they have been the big winner of every EU election for the past twenty-five years.

The worst fears of the centrists—that the EPP, center-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D), and liberal Renew would not win enough seats to form a majority—has not come to pass. They have far more seats than they need. In the coming month, they will hammer out the details of their coalition agreement and decide whether they want to confirm von der Leyen for a second term, if she is appointed to one by the twenty-seven national EU leaders as expected at a summit at the end of the month. The most important thing to watch will be the group formation talks of ECR and ID. Can they put their differences aside to unite? And if not, who will win the competition to attract the new nonaligned far-right members of the European Parliament, such as those in the new Se Acabó La Fiesta party?

—Dave Keating is a nonresident senior fellow at the Europe Center and the Brussels correspondent for France 24.

The center held, but just barely

The June 6-9 European parliamentary elections featured a swell in support for hard-right parties, but not the nationalist wave that some headlines are proclaiming. The hard right did so well in France that Macron decided to call snap elections. But the hard right did less well in Scandinavia, Spain, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia.

In Romania, the ruling center-left/center right coalition gained more than 50 percent of the vote, and in Poland the center-right/liberal Platforma outperformed the rightist Law and Justice party for the first time. Italy’s hard-right Brothers of Italy party did well. But Meloni, the party’s leader, has steered away from the pro-Russia positions of many other hard-rightists in Europe and maintained a more Atlanticist stance. In Germany, the hard-right AfD did well, but the main story there is the sagging support for the Social Democrats and Greens, as well as the strong showing by the center-right Christian Democratic Union.

Von der Leyen’s election night statement that “the center has held” seems about right, though not by much.

—Daniel Fried is the Weiser Family distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council, former US ambassador to Poland, and former US assistant secretary of state for Europe.

Will Giorgia Meloni be the new Angela Merkel?

Giorgia Meloni could be the new Angela Merkel in today’s EU. The Italian prime minister is the only leader among the big EU countries to celebrate a clear victory after the June 6-9 elections. Unlike Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, her support has significantly grown.

Meloni will be pivotal in Brussels going forward, as she plays three leading roles: Italy’s head of government, leader of the national Brothers of Italy party, and a prominent figure in the ECR group in the European Parliament. Her participation in the new European parliamentary majority is essential. She could help to rebalance some of the economic policies that were failing during the last European Commission, in particular on energy, as well on industry more broadly. She could also help strengthen European support for Ukraine and counter the malign influence of Russia and China on the continent.

It is worth noting that Italian voters didn’t reward the parties that championed anti-NATO narratives. Matteo Salvini’s Lega has not succeeded, and the Five Star Movement has lost a third of its electorate. Conversely, the success of Forza Italia, the pro-Europe and pro-West party led by Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs Antonio Tajani, is another piece of good news for von der Leyen and her winning centrist strategy.

—Paolo Messa is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and founder of Formiche.

Italian influence across European institutions is growing

Meloni’s rise to the top of European decision making was seemingly the talk of the town (or of the continent, in this case) in this election cycle. And yet, the results for Italy’s opposition parties are potentially just as consequential.

Despite being a sitting prime minister, Meloni fared remarkably well, further cementing her position as undisputed leader of her governing coalition and of the European Conservatives and Reformists. In the opposition, other parties remain fractured and nowhere close to the more than 40 percent support that Meloni’s coalition enjoys, but the Democratic Party staged a surprising late surge in the polls and is now poised to secure among the largest representation within the S&D group. Several prominent figures and astute political operatives from the Democratic Party are set to join the ranks in Brussels, including former governor of Emilia-Romagna Stefano Bonaccini and Florence’s mayor, Dario Nardella. Expect them to secure growing leadership positions within S&D. With a weakened Five Star Movement, the Democrats are expected to emerge as the primary opposition force in Italy, although their messaging and stances on various issues, from Ukraine to migration, remain somewhat ambiguous.

Meanwhile, Renew Europe parties faced a particularly bleak election, largely due to their leadership’s inability to forge common ground and present a united front to the electorate. Both centrist parties fell short of the crucial 4 percent threshold required, in Italian elections, to send members to the European Parliament.

Italy now finds itself center stage, from Meloni and her Brothers of Italy leading ECR to the Democratic Party gaining increased clout within S&D. Analysts anticipated a more pronounced Italian leadership in the next European Parliament, but even so, the extent of this influence came as a surprise.

—Nicholas O’Connell is the deputy director for public sector partnerships at the Atlantic Council. He previously worked in Italian politics.

In Poland, the prime minister is strengthened but his coalition partners are weakened

Securing 37.1 percent of the vote, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s center-right Civic Coalition (KO) managed to defeat Jarosław Kaczyński’s nationalist Law and Justice party, which won 36.2 percent of the vote, marking the first time the KO has surpassed Law and Justice in ten years. The other winner was the far-right and anti-EU Confederation political alliance. Its 12.1 percent is the highest vote share in the party’s history. Tusk’s coalition partners, the centrist Third Way and the Left, suffered setbacks, each one securing only about 6-7 percent of the vote.

Having in effect run the KO campaign single-handedly, Tusk will likely emerge stronger, but the poor results for his partners may lead to tensions within his coalition, which came into power after the national elections in October 2023. This will also strengthen Tusk’s position in Brussels. With KO now one of the largest parties in the EPP group, he can present himself as the champion of the pro-EU, anti-populist cause.

For Law and Justice, the result is not likely to lead anyone to question Kaczyński’s leadership. There was no clear sign of which way the party should go, as both members of their radical wing and the centrists associated with former Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki managed to win seats.

The campaign focused mainly on security issues. For the past few months, Poland has seen an increased amount of cyberattacks and arsons, as well as escalating tensions on the border with Belarus. Shortly before the election, a Polish soldier was killed by a migrant trying to cross the border from Belarus to Poland and one of Warsaw’s largest shopping malls burned down. Tusk has laid the blame on Russia and showed that he could speak on national security issues, which he normally does not do. Despite high political polarization, Poles remain largely united on such issues.

Having had national, local, and now European elections in the span of only eight months, all the parties will now be gearing up for the final leg of this electoral marathon—the presidential elections in the spring of 2025.

—Aaron Korewa is the director of the Atlantic Council’s Warsaw Office, which is part of the Europe Center.

In Portugal, the pendulum swings back to the socialists, while Chega underperforms

Only three months after national legislative elections that propelled the center-right Democratic Alliance (AD) to victory, the pendulum oscillated ever so slightly back to the center-left Socialist Party during the European elections. Of Portugal’s twenty-one seats in the next European Parliament, the Socialists won eight and the AD won seven. This will embolden the Socialists domestically, hardening their opposition program and weakening an already fragile minority AD government.

The far-right Chega party won two seats during its European election debut, but the results were bittersweet. For a party that did not exist during the last European elections, two seats are a victory. The party, though, failed to capitalize on its robust national election results, underperforming at the European level. This suggests that portions of the electorate have sobered to the idea of a new far-right party in Portuguese politics.

The far-left parties continue to fall out of favor in Portugal. The Left Block and the Communist-led Unitary Democratic Coalition each dropped a seat in Strasbourg, while the People, Animal, and Nature party lost the one seat it had, knocking it out of the European Parliament entirely. The centrist Liberal Initiative’s gains were the biggest surprise, winning two seats for the first time and showing there is fertile ground for new political thinking in Portugal.

—Andrew Bernard is a retired US Air Force Colonel and a visiting fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

In Germany, a new AfD challenger is emerging—is it leftist or right-wing?

The biggest headline from Germany, as with the rest of Europe, is likely to be that the far right made significant gains. The AfD performed better than in any election it had ever run in, gaining 16 percent of the vote. However, this is hardly close to the 23 percent that polls were indicating for the AfD earlier this year, most likely due to a scandal involving the party that brought Germans out to protest en masse for weeks.

Inversely, the governing Social Democratic Party performed the worst it ever has in any election. Other members of the governing coalition managed to hold onto their base numbers, with the Greens winning around 12 percent (down from a peak of around 20 percent five years ago) and the Free Democrat Party remaining at 5 percent.

But the real news from my view is the emergent Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance. Wagenknecht was a well-known political star of the Left party for years until she broke off to form her own party late last year. This is the first election her party has appeared in and it managed to claim six parliamentary seats. Wagenknecht has been courting a particular and peculiar left-right political line that encourages a strengthened welfare system along with harsher laws against immigration and welfare for migrants. She is particularly popular in the former East Germany, where the AfD also has its strongest base.

Wagenknecht seems to be peeling voters away from the AfD while also attempting to appeal to voters who are put off by AfD’s extreme right-wing image, but who may agree with its tough-on-immigration platform. Wagenknecht is signaling that the right may be electorally divided, but right-wing issues, particularly when it comes to immigration, will be here to stay in upcoming elections.

—Carol Schaeffer is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a policy fellow with the Jain Family Institute.

In Spain, the center right wins, but a referendum against Sánchez fails to materialize

Sunday’s results from Spain did not drift too far from last year’s national elections, with the center-right Popular Party (PP) winning by a narrow margin over Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez and the ruling Socialists (PSOE). PP won 34 percent of the vote and secured twenty-two of Spain’s sixty-one European parliamentary seats, with PSOE grabbing twenty seats. PP leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo ran the campaign as a national referendum against Sánchez, focusing on corruption allegations and criticism of his policy of amnesty for Catalonian separatists. The results, though, are not overwhelming enough for Sánchez to call for new national elections.

One of the reasons for PP’s failure to gain ground was its inability to stem the growth of far-right parties. Vox gained two seats, which gives it six seats in the next European Parliament, while the reactionary far-right Se Acabó La Fiesta gained three seats. For the PP to govern again, it will have to find a way to either win back voters from Vox or learn to govern with them.

As for Sánchez, he and the Socialists will continue to cling to power, thanks to a strong showing in Catalonia. The prime minister continues to bank on Catalonian stability as a recipe for success.

—Andrew Bernard is a retired US Air Force Colonel and a visiting fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

The Czech political landscape remains highly fragmented

The European Parliament elections yielded surprising results for Czechia this year. Voter turnout reached a historic high of 36.45 percent, significantly surpassing the 28.72 percent turnout in the previous elections and the dismal 18.2 percent turnout in 2014. This high turnout appears to reflect a broad vote against the government, particularly benefitting far-right, populist, and Euroskeptic parties and echoing the successes of opposition parties in Germany and France.

As seen in the past four elections, the European parliamentary elections acted as a referendum on the ruling party. The opposition party Action of Dissatisfied Citizens (ANO), led by former populist Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, reaffirmed its position as the strongest entity in the Czech political arena, securing 26.14 percent of the vote. Despite this, the ruling coalition, made up of two coalitions of five parties, secured more seats in the European Parliament, picking up nine seats while ANO won seven. The main coalition party, Together, received 22.27 percent of the vote, translating to six seats. The ruling coalition expressed satisfaction with its results, viewing it as valuable feedback from the voters. However, losses for some coalition parties signal potential trouble for Prime Minister Petr Fiala’s government ahead of the national parliamentary elections in late 2025.

Commenting on the election outcome, President Petr Pavel stated on X, “We cannot ignore the rise in support for extremists in Europe,” adding that “we need to take note of these voices and think about why this is happening.”

The right-wing alliance Oath and Motorists, focusing on “protecting combustion engine cars from the EU” and combating illegal migration, garnered 10 percent of the vote and won two seats. The left-wing coalition Enough!, consisting of three parties including the Czech Communists, also secured two seats.

With these results, the Czech political landscape remains highly fragmented, with twenty-one European parliamentary seats divided among seven entities, four of which are coalitions.

—Patrik Martínek is a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center, currently in residence from the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Further reading

Sun, Jun 9, 2024

As the far right rises in Europe, can the center hold?

Fast Thinking By

Elections for the 720-seat European Parliament concluded on Sunday. Three Atlantic Council experts share their insights on the initial results.

Mon, Apr 15, 2024

Your primer on the European Parliament elections and how they will shape the EU

Eye on Europe's elections By

As Europe heads to the polls to elect the 10th European Parliament this June, the Europe Center is breaking down the key people and issues to know.

Thu, May 9, 2024

The European Parliament is still learning its lesson from corruption scandals

New Atlanticist By

With European Parliament elections upcoming, EU institutions should codify stricter definitions of foreign influence and interference, and they should pass additional reforms to ensure transparency.

Image: PARIS, FRANCE - JUNE 2: Jordan Bardella, President of the National Rally (Rassemblement National), a French nationalist and right-wing populist party, speaks to over 5,000 supporters at his final rally ahead of the upcoming European Parliament election on June 9th, at Le Dôme de Paris - Palais des Sports, on June 2, 2024., France, on June 2, 2024, in Paris, France. Photo by Artur Widak/NurPhoto.