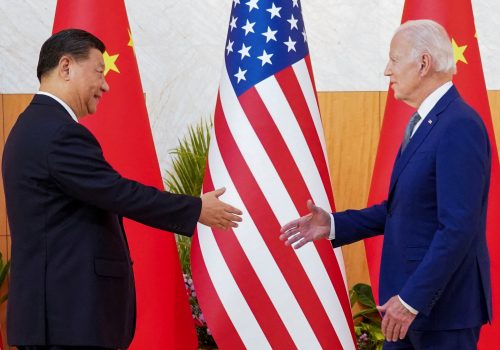

Experts react: What did Biden and Xi’s ‘candid’ meeting accomplish?

They talked, and walked, but did they deliver? On Wednesday, Chinese leader Xi Jinping met US President Joe Biden at an estate outside of San Francisco, during the ongoing Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit. In his opening remarks, Biden said that while the two leaders often disagreed, he appreciated that conversations with Xi were often “candid, straightforward, and useful.” There was certainly a lot to talk about, from the Israel-Hamas conflict and Russia’s war in Ukraine to North Korea’s nuclear arsenal, and from artificial intelligence (AI) risks to a raft of trade disputes. But specific outcomes (at least those shared publicly) were mostly limited to a reopened military-to-military hotline and new coordination to curb fentanyl trafficking from China. So was the four-hour meeting good for US-China relations? Below, Atlantic Council experts get candid about this question and more.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Colleen Cottle: Will efforts to stabilize the relationship withstand the next crisis?

Dexter Tiff Roberts: Xi is putting on a friendly face as China’s economy slumps

Hung Tran: This relationship needs more than ‘guardrails’

Kenton Thibaut: How China is shaping the narratives of the meeting—with the Global South in mind

Andrew A. Michta: China’s military buildup will continue to destabilize the region

Joseph Webster: Climate talks were constructive but insufficient

Niels Graham: Great power competition is more benign when both sides think time is on their side

Matt Geraci: While the US turns away from trade agreements, China seeks more

Rayhan Asat: Human rights must not be left outside of the meeting halls

Will efforts to stabilize the relationship withstand the next crisis?

Biden seems to have made the most of his meeting with Xi, which achieved the admittedly low bar for success, at least in the near term. The meeting afforded Xi the optics he desired—including the warm greeting and handshake from Biden when Xi arrived—to nudge him toward more candid discussions. The get-together offered Xi plenty of photos to use for a campaign to try to woo foreign investors back to the Chinese market, a key priority for Xi as he seeks to bolster the Chinese economy. (Following the Biden meeting, Xi dined with American business executives.) The two leaders covered a lot of ground in their private discussion, according to Biden’s recap during his press conference afterward, even if no resolution was reached on some specific US requests such as the release of US citizens being detained in China. Two of the summit’s three primary deliverables were widely expected—fighting the flow of fentanyl and its precursor components and the resumption of high-level military-to-military communications. The third was less anticipated but notable: coordination on AI risks and safety issues. And the overarching message of the summit was clear—that both sides see value in stabilizing the relationship and are committed to maintaining high-level communication even as they continue to vigorously compete.

Nonetheless, the durability of that success will only become apparent in the weeks and months ahead. When Biden and Xi met on the sidelines of the Group of Twenty (G20) summit in Bali a year ago, they struck a similarly optimistic note about the value of stabilizing the relationship and maintaining dialogue, which quickly faded as tensions flared over the suspected Chinese surveillance balloon floating over the United States. The painstaking preparations for this year’s visit and Chinese state media’s recent softening of its tone toward the United States offer a good foundation for maintaining open lines of communication. And the fragile Chinese economy might also serve as a useful check on any escalatory impulses from Beijing that could further repel foreign investors. However, when the next unexpected bump in the relationship inevitably comes—the next surveillance balloon or cyber incident, or perhaps an even nearer miss between Chinese and US forces in the South China Sea—will the two leaders really be able to pick up the phone and talk it out? Time will tell.

—Colleen Cottle is the deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub. She previously spent over a dozen years at the Central Intelligence Agency serving in a variety of analytic and managerial roles covering East and South Asia.

Xi is putting on a friendly face as China’s economy slumps

“The global economy is recovering, but its momentum remains sluggish,” Xi said just before his meeting with Biden at the ongoing APEC Summit. The reality: The weak economy that Xi is really worried about is China’s. Indeed, the fact that Xi met at all with Biden, and the degree to which he has offered concessions (the fentanyl deal and resumption of military-to-military exchanges, to cite two examples), has everything to do with the protracted slump now ongoing in China’s economy.

A wake-up call signaling just how bad things have gotten was the shocking announcement earlier this month, that foreign direct investment fell in China in the third quarter, the first time in a quarter century that companies have pulled money out of the country. As things turn south for its own private firms (whose confidence has fallen to its lowest since 1978, according to one well-placed Chinese financier), Xi knows China needs multinationals to keep investing and creating jobs (particularly important for Chinese youth, more than 20 percent of whom in urban areas were unemployed, according to the last-released figures). And for now, that’s not happening as businesses from around the world, including American ones, have turned sour on the Chinese market.

Xi’s worries about the parlous state of the Chinese economy are also behind his decision to join a banquet in his honor with corporate chieftains, including Apple’s Tim Cook, BlackRock’s Larry Fink, and Visa’s Ryan McInerney, shortly after his meeting with Biden on Wednesday night. So even as Xi doesn’t seem to be getting much in return—the Trump-era tariffs aren’t going away, and the growing curbs on China’s access to advanced technology, including semiconductors, aren’t being reversed—he’s putting on a friendly face for his first visit to the United States in over six years.

—Dexter Tiff Roberts is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Indo-Pacific Security Initiative in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security and Global China Hub.

This relationship needs more than ‘guardrails’

Despite low expectations, the Biden-Xi summit has produced some useful results—including resuming direct military-to-military contacts, agreements to discuss potential risks of AI, and cooperation on climate change and on curbing the flow of fentanyl feeding the US opioid crisis. These outcomes can help keep US-China tensions from getting out of control—something useful for both leaders in the year ahead. Biden can focus on his increasingly challenging reelection campaign, and Xi can devote his attention to reviving China’s sputtering economy.

Nevertheless there is a risk of miscommunication, setting the stage for disappointment. By emphasizing the need for “guardrails” to keep relations from veering into conflict (a sensible idea in itself), the United States could risk sending the wrong message, that the current situation can be tolerable if it does not escalate further. US allies in the Asia-Pacific directly exposed to China’s threats over maritime and border disputes may not find such a message reassuring: It’s China that unilaterally wants to alter the status quo by threats of force and that needs to change its behaviors. Beijing also wants change, namely for the United States to end its high-tech containment of China, so that it can continue to develop and change the current international political and economic system in its favor.

—Hung Q. Tran is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center.

How China is shaping the narratives of the meeting—with the Global South in mind

In the lead-up to the meeting between Xi and Biden in San Francisco, Chinese state media has depicted the meeting as a triumph of “Xiplomacy” and Xi’s leadership. English-language coverage of the event in Chinese state media focused on Xi’s warm reception in San Francisco and outlined the benefits of positive relations for both sides. Chinese-language coverage highlighted Xi’s forward-leaning role in seeking to stabilize relations and also heavily emphasized the high turnout of overseas Chinese people and the diaspora community at the event, seeking to depict to a domestic audience the global support for Xi. Additional commentaries in state-owned outlets all over the world have emphasized China’s activities through APEC as contributing “Chinese solutions” to building “a community of shared future for mankind” and to bringing prosperity and development to the region—messages that resonate especially in the Global South. The coverage is meant to depict both to the global and domestic audiences that China—and more especially Xi—is the party that is seeking to stabilize the US-China relationship for the good of the world and that China is a responsible global leader. These messages are also designed to set up China’s response should the outcome of the meeting and of the summit itself not yield fruit.

The main message will be that China put aside tensions to try and work with the United States for the global good, but that the United States was willing to sacrifice the benefits to the rest of the world that would come from a stabilized US-China relationship in the service of its own interests. This messaging taps into existing worries in regional blocs like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, where the debate on how to manage rising tensions between the United States and China has become an area of increasing concern. Hopefully, the two sides can reach some sort of détente in this downward spiral, but the United States should be aware of the messages that China may use following the outcomes of the meetings—domestically and across the world—should things go south.

—Kenton Thibaut is the resident China fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab.

China’s military buildup will continue to destabilize the region

While issues concerning the ever more difficult economic relations between the United States and China drive the summit headlines, China’s military buildup is the biggest elephant in the room. Beijing has been relentlessly expanding its military capabilities across domains, with the People Liberation Army (PLA) Navy, though inferior to the US Navy when it comes to capabilities, already numerically bigger than the United States’. The PLA is expanding at scale, with China aggressively pursuing cutting-edge military and dual-use technologies to reduce the qualitative gap with the US military. This rapid shift in relative military capabilities continues to destabilize the region, and China’s close alliance with Russia raises the risk of Beijing gaining access to some of Russia’s advanced military technology.

—Andrew A. Michta is director of the Scowcroft Strategy Initiative and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

Climate talks were constructive but insufficient

The climate provisions that came out of the latest summit between top climate officials from the United States and China—and released in a statement one day ahead of the Biden-Xi meeting—were constructive and welcome, but insufficient. The United States and China agreed to step up cooperation on the reduction of methane, a particularly dangerous greenhouse gas, and each committed to advance at least five large-scale cooperative carbon capture and underground storage projects by 2030.

Still, the statement leaves much to be desired. Both sides agreed to “pursue efforts to triple renewable energy capacity globally by 2030.” The focus on capacity is misplaced. The world needs actual generation of renewable electricity to displace fossil fuels, especially coal, not just capacity. Moreover, the misplaced emphasis on capacity—rather than generation—is a subtle concession to Beijing’s environmentally inefficient deployment of renewables.

Finally, the statement only contains a passing mention of the world’s most vital commodity: water. China is likely staring down an increasingly water-stressed future—potentially even a looming water crisis—that could force Chinese policymakers to make difficult trade-offs between food, energy, and water.

Despite the statement’s shortfalls, it’s highly constructive that the two sides are talking about the climate again. A single meeting can’t fix all the world’s climate problems, but hopefully it can begin to foster a common understanding of the immense climate challenges confronting humanity.

After all, 千里之行,始于足. A thousand-mile journey begins with a single step.

—Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Global Energy Center and editor of the China-Russia Report.

Great power competition is more benign when both sides think time is on their side

With little to no progress on several major issues—semiconductors, tariffs, and Taiwan—affecting the US-China relationship, Biden’s meeting with Xi did little to resolve the underlying points of tension in the US-China relationship. Washington continues to view China as a systemic rival while Beijing remains convinced that the United States is trying to constrain it. However, neither Biden nor Xi expected—or intended—to overhaul the bilateral relationship in this meeting. Instead, it was an opportunity for both sides to set expectations and mitigate risks. The limited areas of policy agreement are a sign that both sides are willing to engage in some cooperation in the short-term, but neither is willing to divert from a broader course of strategic competition.

A range of factors are incentivizing short-term cooperation. The ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East, as well as a national election in 2024, mean Washington has little appetite for another crisis involving China. Beijing would also rather focus its attention on revitalizing its domestic economy. Chinese growth has stumbled after a year of zero-COVID policies, combined with a structural slow-down in the economy. It’s unlikely either of these dynamics will shift in the next year. Barring an unexpected crisis, then, there is some hope that the Biden-Xi meeting will initiate the start of a period of relative calm in the relationship. Though, this may only last until either Washington or Beijing decides that they are once again in a position to actively compete.

—Niels Graham is an associate director for the Atlantic Council GeoEconomics Center where he supports the center’s work on the Chinese economy and US international economic policy in the Indo-Pacific.

While the US turns away from trade agreements, China seeks more

Biden came to the APEC Summit this week aiming to showcase the United States as a strong economic partner with Asia-Pacific countries, but he did not come with the promise of any new trade deals. Meanwhile, China has been rapidly building out its free trade agreement (FTA) network through bilateral and multilateral agreements. So far in 2023, China has signed two FTAs (with Serbia and Ecuador), initiated negotiations with Honduras mere months before they switched diplomatic ties from Taipei to Beijing, and began consultations with Papua New Guinea. Accounting for bilateral and regional efforts, China has now signed twenty-three FTAs, with another fourteen under negotiation and six under consideration (often through conducting joint feasibility studies). The United States, on the other hand, has fourteen comprehensive FTAs in force with twenty countries, and it put its last comprehensive bilateral FTA into effect in 2012.

With the Biden administration’s proposed Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) facing strong political headwinds, such as disagreements on enforceable labor standards even within the Democratic Party, and the 2024 election coming into full swing, the United States risks signaling to global partners that it is not a reliable economic partner and that the IPEF could be doomed to a similar fate as the US withdrawal of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Overall, China’s focus has been negotiating bilateral trade agreements with APEC countries (many of which happen to be part of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership that entered into force January 2022). At the same time, China has been pursuing multilateral trade agreements with regional groups, such as its ongoing negotiations with the Gulf Cooperation Council.

Whether pursuing FTAs or a broader framework, such as the IPEF, is the answer for the United States to better compete with Beijing, Washington needs to show it can deliver on its promises, such as the new cooperation on clean energy and anti-corruption pillars of the IPEF that have recently been agreed upon. Most importantly, the United States needs to reassure partners that an agreement on the IPEF’s trade pillar will have staying power no matter who sits in the White House. US policymakers should not ignore China’s “FTA diplomacy” agenda, since Beijing seems happy to fill in any gap left by the United States.

—Matt Geraci is an assistant director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub.

Human rights must not be left outside of the meeting halls

The high-level meeting this week revealed two contrasting realities. In one world, influential figures convened with Xi to address a range of global issues, from the fentanyl crisis affecting many Americans to broader matters of international significance. Among them were the ultra-rich chief executive officers of multinational corporations, who not only paid their way to dine with Xi but also honored him with a standing ovation, seemingly disregarding the allegations of human rights abuses linked to his government.

In the other world, outside the meeting halls, activists assembled to express their dissent, protest against injustices and crimes against humanity, and resist the status quo. These courageous individuals, who not only bear the potential consequences of the Chinese regime’s actions but also the outcomes of discussions between Biden and Xi, found themselves excluded from the confines of the meeting rooms.

As a human rights lawyer, this stark contrast prompts contemplation for me on how to bridge these two disparate worlds. Do the voices of civil society affect US foreign policy? If so, the question arises: Does and will Biden genuinely prioritize human rights, especially given recent actions, such as the removal of sanctions on Chinese entities associated with human rights abuses and genocide as determined by the US government?

—Rayhan Asat is a nonresident senior fellow with the Strategic Litigation Project at the Atlantic Council. As an international human rights lawyer, she focuses on international human rights, atrocity prevention, the rule of law, civil liberties, corporate accountability, and international law.

Further reading

Tue, Nov 7, 2023

How Biden can make the most of a meeting with Xi

New Atlanticist By Colleen Cottle

The US president and Chinese leader are expected to meet on the sidelines of the November 15-17 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in San Francisco.

Tue, Nov 7, 2023

What to expect from the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum

Econographics By Niels Graham

On November 15th US will host the Annual APEC Forum. There, the US is expected to make major announcements around its regional trade agreement, bilateral investment commitments, and a meeting with China's Xi Jinping.

Wed, Nov 15, 2023

China’s support for Russia has been hindering Ukraine’s counteroffensive

New Atlanticist By Markus Garlauskas, Joseph Webster, Emma C. Verges

A deep dive into trade data reveals how materials imported from China are vital for Russia’s ability to sustain its continued stubborn efforts to hold onto Ukrainian territory.