Germany, a pioneer of the industrial revolution and one of the most technologically advanced countries on the planet, is facing a shortage of experts and engineers, a Spiegel report argues. The problem is an outdated immigration policy.

Germany, a highly industrialized nation dependent on its technical expertise, extends only a limited welcome to qualified foreigners. But it is an immigration policy which threatens to gamble away the country’s future. For years, German politicians have wasted valuable time in an international competition for talent with their half-hearted immigration and integration policies. And now, just as the country seems to have emerged from a major crisis, the alarmists are issuing new warnings. In a knowledge-based society, well-trained people are the most important and scarcest form of capital. While other industrialized nations have been courting skilled foreign workers for years, Germany has discouraged these highly qualified people and continues to do so today. Now, however, globalization, demographic changes and economic demands require a new, modern immigration policy. The country doesn’t have much time left to change its policies.

German companies are already complaining about a lack of skilled workers. According to the German Association for Information Technology (BITKOM), the industry is currently seeking 20,000 IT specialists. And the Association of German Engineers (VDI) says that Germany needs 35,000 more engineers than are currently available. The shortage applies to all sectors.

The German Federal Employment Agency notes that the current need for skilled workers extends beyond computer specialists and technicians. Lathe operators, metal workers, grinders, social workers, nurses and nursing home workers are also in short supply.

The Expert Council of German Foundations on Integration and Migration (SVR) estimates that the German economy is already losing about €20 billion ($26 billion) in value a year as a result of these developments. And the dilemma isn’t even all that new. Germans have been discussing the biggest problem — demographic change — for decades, but now it has suddenly arrived.

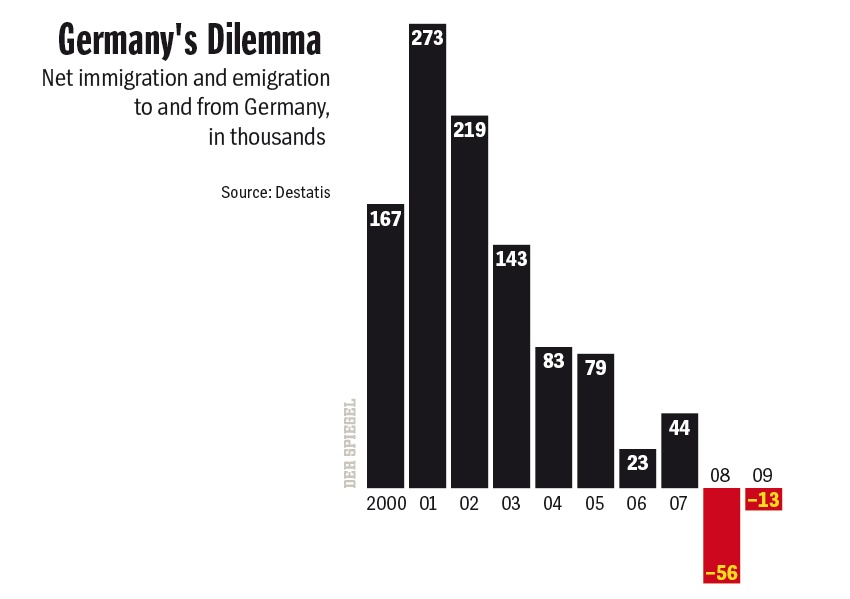

The population is shrinking drastically. When the first baby boomers retire starting in 2015, the older Germans leaving the work force will likely outnumber young people just entering the labor market.

Germany’s current labor force comprises about 44.5 million people. In 40 years, absent an increase in immigration, that number will have dropped to only 26 million.

Solving the problem, alas, will require a major cultural change.

After its postwar economic miracle, Germany traditionally brought in guest workers to perform the jobs that were poorly paid and required little qualification. Because most moderately educated foreigners were only expected to stay in Germany temporarily, integration policy was long merely a matter of debate with little connection to real needs.

The Gastarbeiter, predominately Turks, were happy for the opportunity to work in a much wealthier country, even though they and their children could never attain social integration into German society, much less citizenship. But that system will not attract highly educated labor with their pick of places to work.

"Germany has significantly more poorly qualified immigrants than other OECD countries. Unlike Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Australia, we have not managed to control immigration in a targeted manner," says IAB expert Brücker. Despite some improvements, particularly for academics and management personnel, the country still isolates itself instead of opening its doors. The 2005 Immigration Act has in fact curbed immigration.

Experts are arguing Germany needs to lower the bureaucratic barriers to entry, making it very fast and painless for highly qualified workers from outside Europe to get work visas.

Beyond that, though, Germany will have to lose its reputation for being unwelcoming to those from non-European cultures. As IT headhunter Ulrich Dietz puts it, "Everywhere — in China, India, Brazil — there are highly motivated, talented young engineers, and it’s our job to convince them that they want to go to Germany. German society has to open up more. Unfortunately, people from other countries, Indians, for example, are still not fully accepted." Right now, the United States and other more diverse societies are winning the competition for talent.

James Joyner is managing editor of the Atlantic Council.

Image: germany-migration-patterns.jpg