Once again, China pushes for economic stimulus, hoping for a different result

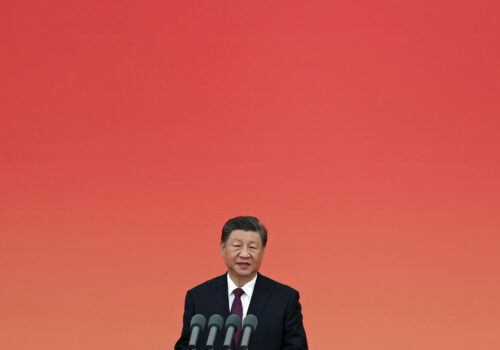

Chinese leader Xi Jinping is selling optimism, but China isn’t buying. Over the past four months, his government has repeatedly announced stimulus measures to revive the country’s stumbling economy, while claiming that everything is going splendidly. Then, when those policies prove inadequate, the stock market sinks, the economy lingers in the doldrums, and Xi tries again.

That pattern started to reemerge last week after the Chinese leadership’s annual conclave on economic policy. Xi declared in his keynote speech during the December 11-12 conference that “the economy is stable and making progress . . . and the main economic and social development goals and tasks are about to be successfully completed.” The conference communiqué announced that the most important policy task in 2025 will be to “vigorously boost consumption” through “moderately loose monetary policy” and “more active fiscal policy.”

The reception was decidedly mixed. Echoing many other observers, investment bank Morgan Stanley called the government announcement the “most aggressive stimulus tone in a decade,” but also said that “implementation remains uncertain.” In the absence of concrete details accompanying the announcement, China’s stock markets immediately tanked. In a country that lacks other outlets for public opinion, it was a clear vote of no confidence.

This lack of confidence should come as no surprise. Amid economic problems that include weak household consumption and anemic business investment, a property market collapse, high youth unemployment and deflation, the Chinese government is not facing up to a root cause of the downturn. It has spent five years stifling the country’s once-dynamic private sector. Policies that favor state-owned enterprises and give center stage to state planning have come at the expense of a market economy hit by tight regulation and Chinese Communist Party interference. “Building entrepreneurial confidence depends primarily on the reform direction, not on the strength of monetary policy stimulus,” said Zhang Weiying, a leading Chinese professor of economics, in an August speech. “However, recent practices suggest that focusing solely on [monetary and fiscal] solutions cannot fundamentally resolve China’s economic challenges.”

There is also an important international dimension to the policy choices Xi faces. China is the largest driver of global demand, and many countries need China to sustain a high level of import demand. But imports have been falling as the economy struggles, and Beijing has relied on export growth to keep China’s manufacturers alive. As a result, trade tensions are rising as a flood of Chinese goods hits both advanced and emerging market economies. And with President-elect Donald Trump threatening new US tariffs against China, the Chinese government will need to look to domestic drivers of growth.

The government certainly can do more to boost demand. The stimulus measures taken since September have focused on increasing credit, supporting local-government purchases of China’s vast store of unfinished or unsold homes, and restructuring the massive debt of local governments. In addition, Beijing is spending heavily on developing advanced technologies and building infrastructure, but the benefits of those expenditures—especially for more roads and railways—appear to be more limited than in the past. Most importantly, corporate and household borrowing has failed to gain momentum despite the easy credit—a sign of the depressed confidence that has undercut consumption and investment. Weak November retail sales and home sales figures show that, as far as consumers are concerned, it’s not nearly enough.

The true scale of the economic downturn has recently received attention in China through widely circulated comments by private sector economists. Earlier this month, Gao Shanwen, chief economist at SDIC Securities, was quoted as saying that post-pandemic China is “full of vibrant old people, lifeless young people, and despairing middle-aged people,” and he suggested that as many as forty-seven million people are unable to find formal work in China’s cities. Gao also estimated that the country’s economic growth over the past three years may have been overstated by 10 percentage points.

Meanwhile, Fu Peng, an economist with Northeast Securities, highlighted the plight of the country’s poor, saying on December 4: “Whenever the economy contracts, it’s those at the bottom who suffer the most at first. However, that barely has any impact on the macroeconomic data.” Not long ago, such critiques would have been just a small part of a wide-ranging policy debate that used to take place in China. But now, in the country’s current climate of strict control over all policy discussions, both economists’ remarks were removed from the Chinese internet after a few days and their social media accounts were restricted.

Public criticism of government economic policies has not been limited to private sector economists. “In recent years, the lack of effective demand in China can . . . be attributed to the government failing to return income to the public while itself also not actively spending,” said Xu Gao, chief economist at the state-owned Bank of China International in a September speech.

The Chinese government’s economic policy communiqué last week does speak of a “greater focus on benefiting people’s livelihood.” But it only cited a program introduced at an earlier stage of the stimulus effort to subsidize trade-ins of cars and household appliances. There was no new reference to income subsidies or other initiatives to directly assist China’s unemployed and underemployed, especially those in the construction and real estate industries who have lost work and millions of recent university graduates who are unable to find jobs. There also has been no talk of using the government’s central bank digital currency to make direct payments to consumers.

Since China’s middle class can buy only so many refrigerators and electric vehicles—even with government subsidies—the big question is whether Beijing is prepared to consider a wider effort to support consumers. However, Xi previously has expressed skepticism about “welfarism,” and he has spoken positively of his own experience during China’s Cultural Revolution of having to “eat bitterness.” So, public assistance may prove a bridge too far for a party that rose to power nearly eighty years ago claiming to represent China’s less fortunate citizens.

Perhaps it will take another shock to the system—for example, a sharp drop in exports—to jolt China’s rulers out of their current failing approach.

Jeremy Mark is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center. He previously worked for the International Monetary Fund and the Wall Street Journal Asia. Follow him on X: @JedMark888.

Further reading

Fri, Nov 22, 2024

The United States has trade leverage with China, but not as much as Washington thinks

Sinographs By Josh Lipsky, Mrugank Bhusari

Diversification away from China is proving far more difficult for high value-added goods such as electronics - and the incoming Trump administration knows that.

Wed, Nov 13, 2024

The Trump trade wars are coming back. Here’s what to expect this time.

New Atlanticist By Josh Lipsky

Donald Trump’s belief in tariffs is deeply rooted, and the incoming president is resolved to fill out his administration with those who will support his vision on trade.

Mon, Oct 21, 2024

China’s economic stimulus isn’t enough to overcome that sinking feeling

New Atlanticist By Jeremy Mark

Local governments are struggling under large amounts of debt, the property sector is heavily burdened, and Chinese leadership is preoccupied with just keeping the economy afloat.

Image: A man rides a scooter past a giant screen showing news footage of Chinese President Xi Jinping attending a Chinese Communist Party politburo meeting, in Beijing, China December 9, 2024. REUTERS/Tingshu Wang