As Beijing has intensified its efforts in recent weeks to overcome China’s economic slowdown, speculation has centered on the prospects for a combination of monetary easing, government spending, and investment incentives that will create a “bazooka” stimulus. But the measures announced so far to address the country’s property crisis, falling prices, hoard of local-government debt, and plummeting business and consumer confidence, look unlikely to produce a sustained rebound.

A more apt metaphor can be found in the recent satellite photograph of salvage vessels trying to refloat a Chinese submarine that sank while under construction. The reality is that the seventeen trillion dollar Chinese economy is weighed down by problems that will require much more than the current policy response.

Chinese leader Xi Jinping apparently has opted for a mid-course correction emphasizing lower interest rates, reduced regulation of the property market, stock market pump-priming, and debt swaps for local governments. Plans for a budget increase are expected toward the end of this month, but hopes are fading for the kind of spending that would jump start domestic demand. With millions of empty and unfinished apartments, high youth unemployment, falling salaries, and policies prioritizing high-tech industries over sectors that are the backbone of the economy, China is on track to muddle through. The outlook is for more of the status quo: businesses that don’t invest, consumers who won’t consume, and local governments that can’t deliver services.

The impact of this mismanagement has become impossible to ignore.

The initial euphoric response to the government’s turnaround from the stock market has been replaced by disappointment, and Chinese officials have scrambled to announce additional “goodies.” Among the most recent were the measures to stimulate the property market, including reduced restrictions on apartment purchases and a package of loans to already deeply indebted developers. When that failed to reignite investors’ enthusiasm, the central bank announced $112 billion of loans and swaps to support the “steady development” of the market.

The public skepticism exemplified by China’s 200 million stock market participants has deep roots after several years of economic mismanagement. Beijing’s drive to achieve annual economic growth targets—which some analysts regard as “smoke and mirrors”—was powered by relentless investment in industry, infrastructure, and real estate. For all the country’s success of the drive to build electric vehicles and high-speed trains, the economic landscape has been marked by waste. By one estimate, more than fifty million residences currently sit empty nationwide, and millions more are unfinished. The industrial expansion produced “enormous structural overcapacity” that the slowing economy could not absorb, only amplifying the problems of indebtedness and supercharging the country’s export efforts—and trade tensions.

The music stopped in 2020 when government regulators turned off the taps on real estate lending. Dozens of developers soon collapsed, and local governments no longer could finance their profligacy with land sales. Provinces, counties, and cities are on the hook for some 100 trillion renminbi (fourteen trillion dollars) of debt, about 60 percent of which is classified as “off balance sheet.” Beijing made matters worse with its disastrous zero-COVID 19 policies, which undermined growth and decimated confidence. That fiasco was accompanied by a crackdown on many of the country’s most dynamic private sector companies that choked off private investment and closed off a source of jobs for college graduates. It was at that point, in the face of rising US-China tensions, that Xi doubled down on his pursuit of technology self-reliance, diverting resources that might have helped address the economy’s more immediate woes.

The impact of this mismanagement has become impossible to ignore. Home sales have plummeted 24 percent so far this year, and household savings are soaring. Producer prices have fallen for two years straight as factories pump out goods that can’t be sold, and consumer prices hover on the brink of deflation. Industrial output and fixed capital investment have lost momentum, and even export growth is slowing, in part because of falling prices. Measures introduced by the central bank to encourage investment and property sales so far have fallen flat. For example, only 4 percent of a forty-two billion dollar central bank initiative announced in May to encourage cities to buy unsold homes was taken up as of the end of June.

Beijing’s focus on refinancing local government debt—with discussion of a $853 billion swap to reduce servicing costs—and shoring up state banks with capital injections certainly is needed to ensure financial stability. But the money on offer pales in comparison with the scale of the debt problem, and trying to get businesses and households to open their wallets without more efforts to stimulate demand may prove a dead end in the absence of direct pump-priming. A program to subsidize trade-ins of older cars and appliances has proven popular, leading to a small rise in retail sales. But besides a one-time cash payment to poor families and some money for student loans, the central government has exhibited a pathological aversion to anything smacking of “welfarism.” That means there will be little relief for young people, 18.8 percent of whom—including millions of recent college graduates—were unable to find jobs as of August, according to Chinese government data, whose methodology was revised at the beginning of the year after the jobless figure hit 21 percent.

While the government has shifted from cracking down on China’s private sector to sweet-talking executives, the latest headline initiative sends a less welcoming message. A draft law on “Promoting the Private Economy” unveiled earlier this month clearly delineates that the sector will be expected to “uphold the leadership of the Communist Party of China, adhere to the socialist system with Chinese characteristics, and actively participate in building a strong, modern socialist country.” Businesses also will be required to “accept government and social supervision when engaging in production and operations.”

That is hardly a formula for unleashing China’s once-unbridled “animal spirits.” Although the private sector provides 80 percent of employment in China’s cities and more than half of the country’s tax revenue, its contribution to fixed asset investment fell to 51 percent of the national total as of August compared with 59 percent in August 2019.

Beijing ultimately may have the “fiscal space” to pump more money into the economy. Finance Minister Lan Fo’an, speaking at an October 12 press conference, declared that there is “quite large room to borrow and increase the deficit.” Central government debt is about 35 trillion renminbi, or 26 percent of gross domestic product. Still, with local governments struggling to service more than twice that amount, and the property sector also heavily burdened, the leadership clearly is preoccupied with just keeping the economy afloat. But as with the sunken submarine, even if the economy eventually returns to an even keel, the legacy of mismanagement will linger for years to come.

Jeremy Mark is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center. He previously worked for the International Monetary Fund and the Asian Wall Street Journal. Follow him on X: @JedMark888.

Further reading

Fri, Oct 18, 2024

Toward a coherent framework for US-China tech competition in the Global South

Strategic Insights Memo By Peter Engelke, Samantha Wong

This memo provides strategists and policymakers in the United States and elsewhere with a coherent framework for understanding the competition between the United States and China for technological dominance with respect to the Global South.

Fri, Oct 18, 2024

Capture the (red) flag: An inside look into China’s hacking contest ecosystem

Report By

China has built the world’s most comprehensive ecosystem for capture-the-flag (CTF) competitions—the predominant form of hacking competitions, which range from team-versus-team play to Jeopardy-style knowledge challenges.

Thu, Oct 10, 2024

China’s economic reforms near the ‘end of the line’

Inflection Points Today By Frederick Kempe

Xi Jinping doesn’t believe in the market or economically sensible reforms, and thus investors shouldn’t believe in him. New Atlantic Council research puts this in stark relief.

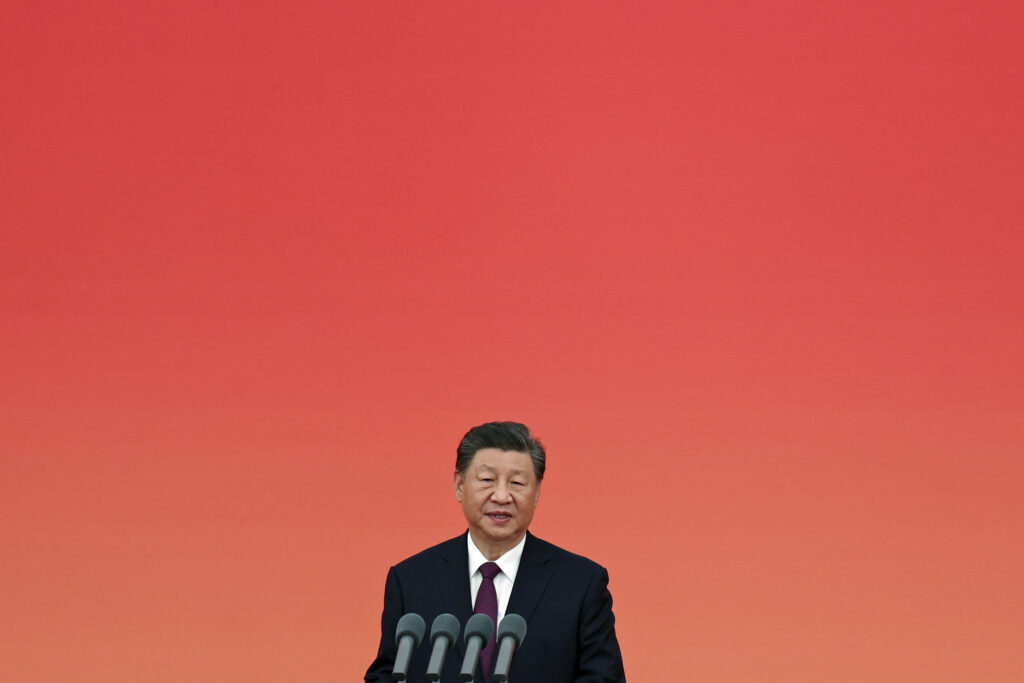

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a speech at a presentation ceremony of national medals and honorary titles, at the Great Hall of the People ahead of the 75th founding anniversary of the People's Republic of China, in Beijing, China September 29, 2024. REUTERS/Florence Lo