Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made a surprise push for constitutional revision in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, drawing significant criticism of his timing. Abe, who initially intended to get changes completed and entered into force by 2020, has let go of the timeline, but not the goal. With more than a year left until September 2021 and the expiration of his term as leader of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the goal of revision might still seem plausible. The coronavirus, however, has shortened the timeframe left for the revision effort with its shifting of the Olympics to 2021, creating an unexpected obstacle for a referendum vote.

While a constitutional referendum has understandable significance in Japan, especially as the proposed changes encompass the controversial Article 9 which enshrines the country’s pacifist principles, the continued level of interest from Japan’s partners and competitors about the effort is difficult to unpack. These actors seem to view constitutional revision, rather than already-enacted legislation from 2015 increasing the scope and authorities of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF), as the key to enabling robust SDF engagement in international security affairs. With revision continuing to make headlines, the process, timeline, and issues at stake are worth rehearsing.

Japan’s national referendum law, passed during Abe’s first term in 2007, establishes the necessary procedures and timelines for a constitutional referendum. It requires a bill to be passed by the Diet with at least a two-thirds majority in both houses, and then a national vote to be held no sooner than two months and no later than six months after passage of the bill. This could be a heavy lift; the massive education and advocacy campaign needed to prepare the public for a vote of this magnitude would, in all likelihood, take closer to six months than two. For comparison, six months passed between the passage of the United Kingdom’s referendum bill and its Brexit vote.

The Olympics, postponed to July 2021 because of the coronavirus, provide a back end to the possible referendum timeframe if it is to be held within Abe’s tenure. They also effectively block off a chunk of time before and during the event that might otherwise be used for the vote or its preparation; given the inevitable attendant protests to a constitutional referendum affecting Article 9, the government would do well to conclude a referendum vote with a few months to spare ahead of the Olympics. That would put the latest reasonable vote in May/early June 2021 and working back six months yields November/December 2020, a mere half year from now.

With this timeframe in mind, Abe’s anxiety to move the issue forward becomes readily understandable. Getting a bill through the Diet by November 2020 would be a tight squeeze. The LDP’s coalition partner, Komeito, is not keen on revising Article 9 and most of the opposition parties are opposed. This leaves much work to be done behind the scenes before the LDP’s proposed revisions are even introduced into the Diet for discussions. If the LDP can drum up the needed support and a bill is introduced, Diet deliberations themselves are likely to be time-consuming; deliberations over the 2015 peace and security legislation, related to Article 9 and similarly controversial, took four months. It seems unlikely that all of these pieces will fall into place in time, but certainly not impossible.

What then is at stake? A look at the prospective changes is instructive, even though translations don’t give the full picture. Draft changes proposed by the LDP in 2018 leave the entirety of Article 9 intact, preserving the language renouncing both war as a sovereign right of the nation and the maintenance of land, sea, and air forces and other war potential. Instead, an additional paragraph is added that translates roughly as follows: “The provisions of the preceding clause shall not preclude the implementation of necessary self-defense measures to defend our country’s peace and independence and ensure the safety of the country and the people, and for that purpose, the Self-Defense Forces, with its supreme commander being the Prime Minister who is the head of the Cabinet, shall be maintained as an armed organization, as provided by law.” The overall effect is to enshrine the SDF in the constitution, formally putting to rest long-standing questions about its status. The real issue, however, lies with the term “necessary self-defense measures,” and how it might serve to cement in place controversial elements of the 2015 legislation and the 2014 reinterpretation of Article 9 that underlies it—most prominent among them, permission, under certain circumstances, for collective self-defense.

For transparency, I find the authorities introduced in Japan’s 2015 peace and security legislation, which I examined in a 2019 paper for the Japan Institute of International Affairs, to be both practical and useful for bringing Japan in line with modern-day security realities while still maintaining a brain-twisting set of caveats, limits, and conditionalities. The collective self-defense envisioned under the peace and security legislation is not the standard sort. It only endorses the limited use of collective self-defense for the specific purpose of defending Japan (as opposed to the explicit defense of another country, the traditional purview of collective self-defense). Even then, the use of force is only allowed when there are no other “appropriate means available” and to the “minimum necessary extent.”

Likely the only counterpart that would qualify under the specifics of Japan’s collective self-defense authorities is the United States. There are a number of other authorities from the 2015 legislation that govern how and under what circumstances the SDF could cooperate with non-US partners, however. These would enable Japan, given political will and the meeting of certain thresholds, to offer SDF participation in military operations to address threats to international peace and security like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan and internationally coordinated operations for peace and security outside of the United Nations framework like the NATO Implementation Force (IFOR) for Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as support to European forces responding to contingencies in the broader region.

All of these measures have been in place since 2016, when the peace and security legislation went into force, without the necessity of any constitutional changes. Only very limited use of them has been made, however, at least in part because of significant sensitivities among Japanese politicians and the public regarding the use of the SDF outside of Japan, as well as legal requirements for the Diet to approve most deployments envisioned under the legislation, including those related to collective self-defense. This is where the constitutional revision becomes pertinent. With self-defense unmentioned by the constitution, its definition and scope has been left up to successive governments, which have traditionally taken a restrictive view. With “necessary self-defense measures” explicitly authorized in the constitution and still undefined, there is a much stronger basis for governments to make a case in the courts for less-restrictive interpretations, less scope for legal challenges to the 2015 laws, and also more basis for politicians to justify less cautious application of the laws. That at least is the concern voiced by some opponents of revision, articulated most forcefully by Craig Martin in a 2019 piece in the Japan Times.

For Japan’s US ally and European partners, any more solid legal footing for the 2015 peace and security legislation that might be provided by constitutional revision can only be a net positive. Although there is still little practical understanding in Europe of the benefits of the SDF’s new authorities for bilateral and multilateral cooperation, the potential impact, including on future NATO operations, is not insignificant. China and North Korea both reacted negatively to Japan’s peace and security legislation, with China accusing Japan of endangering regional peace and security. A related constitutional change would thus likely be spurned by Japan’s competitors, but given that the lid on regional tensions did not come off when the legislation was passed and entered into force, a far more dramatic shift from the status quo in practical terms, then the notion that it would do so as the result of a constitutional referendum is unfounded.

It is for Japan’s people and no one else to decide how they feel about adding language to Article 9. Opinions on the issue are not consistent across recent polls, with a 2020 Asahi Shimbun poll finding 65 percent opposed to amending Article 9 and a 2020 Kyodo poll finding 49 percent in favor. Whether or not the Japanese public will face such a choice in the near future now seems inextricably tied with the coronavirus; either it will scuttle efforts to hold a constitutional referendum before the end of Abe’s term or it will be the impetus for an accelerated effort.

Mirna Galic is a nonresident senior fellow at the Asia Security Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading:

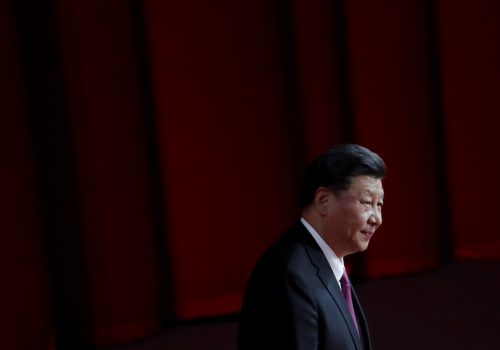

Image: Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe gestures during a news conference in Tokyo, Japan, May 14, 2020. Akio Kon/Pool via REUTERS