The strategic relationship between the United States and India is among the most consequential of the twenty-first century—but the failure of both sides to cultivate their trade ties is holding it back.

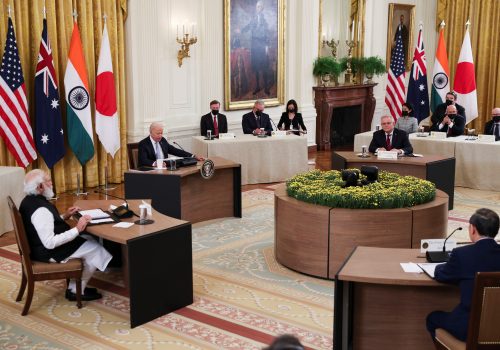

When US President Joe Biden and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met in Washington last month for the first time in Biden’s presidency, their talks on trade were limited and only briefly referenced in a joint statement. This cursory treatment suggests trade has been relegated to secondary importance. Instead, this should be an inflection point for growing the US-India trade relationship, ideally to eventually match the scale and importance of their strategic relationship. Their collaboration in the Quad security dialogue (along with Australia and Japan) reflects shared interests in countering China’s burgeoning regional hegemony and realizing the vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Skeptics who believe prioritizing and boosting trade ties is naïve have their compelling reasons. Earnest efforts to do so in the past proved fruitless (except in some delectable cases), while each country has a shaky history with free trade agreements (FTAs): India pulled away from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and the United States abandoned the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The domestic political environment in both countries is also unfriendly toward new trade deals, and some might argue that neither the United States nor India has shown that it’s ready to deal with the political challenges and vocal opposition that result from related negotiations.

In the absence of any substantive trade agreements, the US-India trade relationship—if measured by agreement obligations—is currently governed solely by the two countries’ membership in the World Trade Organization (WTO). This is unfortunate because they’ve historically been seen as unofficial leaders of conflicting economic blocs (developed and developing countries), even though WTO alliances are more complex and variable than simply that. The WTO continues to fail in producing meaningful results and pursuing reform, and the United States and India are generally at loggerheads on specific issues, from fisheries subsidies to approaches for decreasing market distortions in agricultural trade.

It would be unrealistic to hope that the United States and India might suddenly work together multilaterally on trade, which makes the bilateral trade relationship even more essential for resolving specific trade problems and generating productive dialogue going forward. Yes, the value of US-India bilateral trade and cross-border investments continues to grow—but this part of the relationship between the US and India remains unstable. It’s threatened by a range of risks, including regulatory trends that restrict economic integration and the threat of economic sanctions over India’s defense trade with Russia. To shift toward stability (and ideally more), Washington and New Delhi will need to articulate a joint vision for a deeper, broader, and more integrated economic relationship. The arguments in favor of pursuing a grander vision for trade are becoming increasingly compelling—especially as the trade relationship has stagnated even as the strategic one has leapt forward.

While an FTA is improbable in the near term, trade officials should at least start by laying the groundwork for one. Piyush Goyal, India’s minister of commerce and industry, has already pressed the United States to establish some form of trade agreement, and his meeting with US Trade Representative Katherine Tai at the US-India Trade Policy Forum later this year could be a golden opportunity to chart a course toward stronger trade and investment ties. Here’s what that vision could look like:

- Set the stage. First, the United States and India should establish conditions before either side starts taking steps to execute their vision. That means coordinating more effectively on strategic and trade goals going forward, leveraging the strategic relationship to resolve specific trade irritants, and treating strategic and trade interests as existing in overlapping arenas.

- Tackle the priorities… The United States and India must urgently engage on critical emerging issues that touch on trade. These include digital trade (with a focus on data localization and e-commerce), climate change (with a focus on promoting green markets and avoiding future conflicts over carbon border adjustment measures), and labor (with a focus on worker-centric trade policies). The latter is a priority for both countries, but the United States may press for commitments on specific labor rights, which India—like many other developing countries—may reject as arbitrarily blending trade with labor standards.

- …and leftover issues. Both countries should build a strong record of results on a range of outstanding issues such as market-access restrictions, including tariffs and non-tariff barriers; regulatory alignment, especially to address India’s increasing drive to develop its own standards and testing requirements that could restrict both inbound and outbound trade; limits on services trade, particularly foreign-investment restrictions and non-transparent or redundant licensing requirements; and intellectual property rights and other innovation policies in sectors of mutual interest, such as pharmaceuticals.

- Think long-term. Finally, as Goyal suggested, Washington and New Delhi should develop a long-term vision for trade, including a roadmap toward eventual negotiations on a US-India FTA. Until this happens, each side likely will grow further apart on trade even as they cultivate closer ties with other trading partners. Presenting a clear-eyed, forward-looking vision will justify allocating the resources necessary to pursue and eventually realize it.

There will be risks. In both countries, serious efforts to advance the trade relationship will face challenges in the form of protectionist sentiments and policies. Narratives that characterize certain economic actors—such as Americans who invest in India and vice-versa—as insidious and bent on market, social, or political dominance may set back any progress. This has been especially apparent in the digital economy, even as private-sector investment between India and the United States promises higher growth rates and global competitiveness for both.

Yet despite the risks, establishing a grand vision for the US-India trade relationship would be worthwhile. Biden and Modi should play active roles in integrating their economies more deeply. Failing to do so means the trade and investment relationship will falter—which is not in the strategic interests of either country.

Mark Linscott is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center and a former assistant US trade representative for South and Central Asian affairs, and WTO and Multilateral Affairs.

Further reading

Image: President Joe Biden meets Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the White House on September 24, 2021. Photo by Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters.