Zimbabwe’s government has never before had to deal with a nonviolent civil resistance movement as it is currently facing, according to Chloë McGrath, a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

Zimbabwe’s government has never before had to deal with a nonviolent civil resistance movement as it is currently facing, according to Chloë McGrath, a visiting fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

The non-partisan nonviolent nature of the protests has “really changed the narrative of the way that protests have worked in Zimbabwe in the past and has caught the ruling party off guard because they have never dealt with something like this before,” said McGrath.

Pastor Evan Mawaririe, the founder of the #ThisFlag social movement, was arrested after he mobilized last week’s peaceful protests, which proposed citizens stay home for the day, leaving roads and markets empty and businesses throughout the country closed.

Mawaririe was released on July 13 offering Zimbabweans a glimmer of hope for the future of the nation that is facing political turmoil, human rights violations, and economic despair.

Robert Mugabe, leader of the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), has been in power in Zimbabwe since the country became independent in 1980.

“We’ve reached this critical juncture where the ZANU-PF has been backed into a corner for the first time during its tenure,” said McGrath, noting that the country’s diamond reserves have run out, China is no longer unconditionally offering to bail it out, and civil servants have not been paid for weeks.

Chloë McGrath spoke in an interview with the New Atlanticist’s TK Spandhla. Here are excerpts from the interview.

Q: Zimbabwe has experienced more than sixteen years of political turmoil. Why are the current protests significant?

McGrath: What’s really significant about these protests is that they are strictly non-political. Every kind of previous move toward opposition politics that we have seen as resistance has largely been associated with a party. The national flag, which has been the rallying symbol around this grassroots, citizen-led movement, is nonaligned to any of those movements. It’s grassroots-led, so it doesn’t have party structures or hierarchy, which has given it the ability to be incredibly flexible and move around and adapt to the circumstances that it’s faced by. Also, it’s been distinctly nonviolent, which is one thing that the leaders have continually called for—a commitment to peace and nonviolence. That has really changed the narrative of the way that protests have worked in Zimbabwe in the past and has caught the ruling party off guard because they have never dealt with something like this before.

Q: So the nonviolent aspect of it has been something that ZANU-PF hasn’t really had to deal with before?

McGrath: Exactly. So if you look at what happen on July 6, Pastor Evan Mawarire called for a nationwide stay-away. Specifically asking people not to be on the streets, not to go to work, but to stay home. The country was completely quiet. Normal marketplaces were empty; the streets were empty. That’s a very difficult thing for an oppressive regime to deal with, because what do you do…go into people’s homes to beat them up? No. You can’t really complain about the fact that nobody is around. This was a tactic that took the government by surprise.

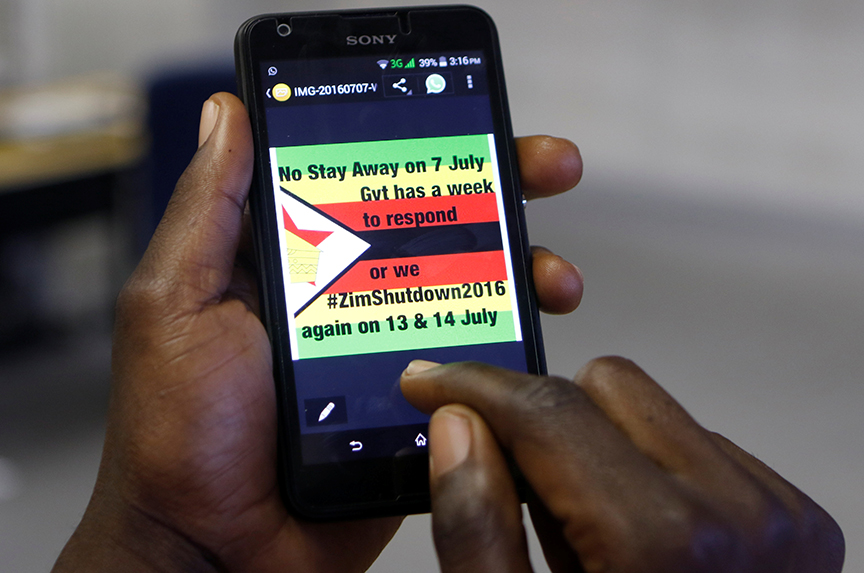

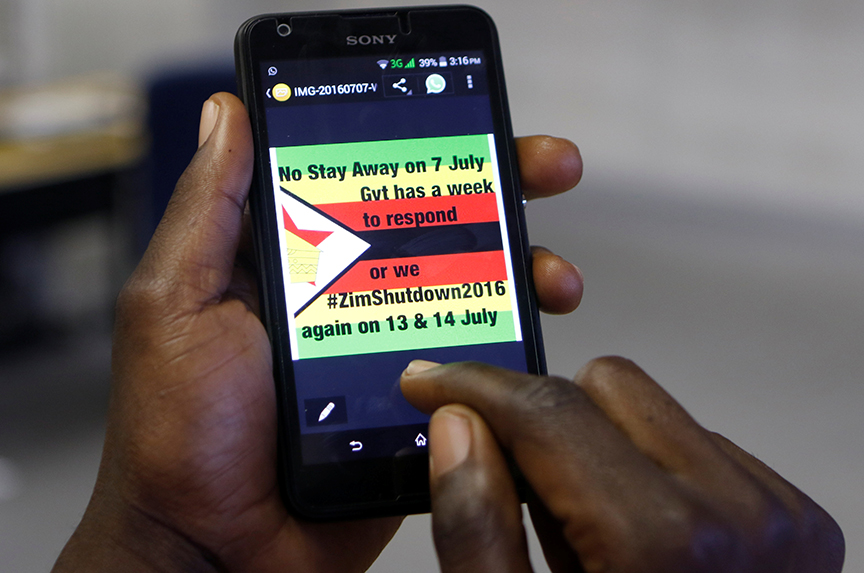

Additionally, I think one thing that has been very important has been the social media usage. Zimbabwe has a very well-functioning central intelligence unit that has offices throughout the country. The use of encrypted WhatsApp messages has really been the main mechanism of communication for people and has also made it difficult for ZANU-PF to respond because people are not gathering together at meetings that can be infiltrated or overheard or broken up…they are doing all of this on social media and across different parts of the country.

Q: What does the release from prison of Evan Mawarire, the leader of the #ThisFlag Internet campaign, mean for the opposition and the civil resistance movement more broadly?

McGrath: Since the government of national unity ended, people have been disillusioned with the opposition. They’ve felt as if the opposition has not really capitalized on the internal fractures within the ZANU-PF and have not provided the leadership necessary to sustain continued pressure on the ruling party. So, this citizen’s movement—that is not politically affiliated—has really given people hope that change is possible. One of the typical tactics that ZANU-PF has used all throughout their time in power has been to detain people, convict them on false charges…and carry out abductions of citizen activists where someone disappears and is never heard from again—as was the case with Itai Dzamara sixteen months ago. Pastor Mawarire is unique in that he was very well known before he was arrested so he has a high profile and there is a great amount of support from people on the ground for his cause. During his hearing at the magistrate’s court, the prosecution changed the charges from theft to subverting a constitutionally elected government. That’s kind of the way a lot of these hearings go down in Zimbabwe, but what was so incredible about July 13 was that Pastor Mawarire’s lawyers pointed out the flaws in the state prosecutors’ actions—you are not allowed to bring new charges against the accused without reading them to the person first. It was on that technicality that the magistrate found that the charges should be dropped, and Pastor Mawawire was let go without bail.

Q: What is the regional impact of the unrest in Zimbabwe?

McGrath: Southern Africa has typically been a very stable and quiet region of Africa, but the last two years have really shown that things are changing. We’ve seen a resurgence of violence in Mozambique recently between the former liberation movement and the current government that is targeting civilians. In South Africa, things are increasingly uncertain politically. Ahead of South Africa’s municipal elections in August, there are a lot of mass demonstrations, rising social unrest, and rioting. We have Zambia as well, which has made some very significant anti-democratic moves in the last few months.

Zimbabwe plays a very pivotal role in the region. This is a common trend where you see former liberation struggle movements shoring each other up in this kind of claim to autocracy and dictatorship that they have had in their country.

The ANC (African National Congress) in South Africa has failed to support any opposition movement against Robert Mugabe because of the liberation struggle credentials that he has. What has been so unique now about this citizen-led social movement in Zimbabwe is that it has managed to recapture some of the liberation struggle terminology and language in a way that hasn’t been done in the past. So [on July 14] there was a very significant event in that COSATU, the trade union in South Africa which is typically aligned with the ANC, broke away from the ANC and commented in support of the mass movements that are going on in Zimbabwe. We are increasingly seeing this kind of movement of normal people working-class people confronting and holding to account liberation struggle parties that are refusing to let go of power.

Q: The IMF is in the final stages of finalizing the conditions for extending a loan to Zimbabwe—the first in seventeen years. Do you expect this move toward re-engagement to help the peaceful civil resistance efforts in Zimbabwe?

McGrath: Zimbabwe has had a difficult time with external involvement in domestic politics. [Since] Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 there’s been a lot of animosity toward Western engagement—neoimperialism and neocolonialism in particular. The Western donor community has not always been politically astute in the way that they’ve engaged in Zimbabwe and that has played directly into ZANU-PF’s hands; it’s been used as a tool of propaganda saying that the West and its financial institutions are undermining the sovereignty of the country. We’ve reached this critical juncture where the ZANU-PF has been backed into a corner for the first time during its tenure. The diamond reserves have run out. The Chinese are no longer bailing them out unconditionally and the country is in a state of national crisis. There is no money. Even civil servants are not being paid. Last month, the military was paid two weeks late. Now, the IMF is in the final stages of re-engaging Zimbabwe and offering to throw Mugabe a lifeline, which will reinvigorate the government, inject cash into the economy, and potentially weaken the case of the protest movement. Zimbabweans have been generally disappointed by the way the international community has not listened to what opposition leaders want, throwing Mugabe a lifeline at this time, no matter the conditions, will be critically damaging toward the people power movement.

The #ThisFlag movement, alongside other emerging social movements, has rekindled a sense of hope and that has been something that has been crushed time and time again over the last thirty-six years. It’s been an incredible move toward unity, across the political divide, across race, across ethnic affiliation and the victory that we saw in the court has made people believe that they can do anything if they unite. The fact that #ThisFlag has rallied around the national flag as an iconic symbol has been very significant as well. People feel that the flag has been typically used by ZANU-PF to represent the party and now it’s being reclaimed as a token of national unity and the power of Zimbabweans to take back their country and to pursue peace and prosperity for everyone.

TK Spandhla is a web assistant at the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @TK_Spandhla.

Image: A man checks a message on his mobile phone in Harare, Zimbabwe, on July 7. (Reuters/Philimon Bulawayo)