Throughout his career, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe worked to “normalize” his country’s military, primarily by attempting to broaden the relatively limited role and mission of its Self Defense Forces (SDF) to better protect Japan in an increasingly unstable world.

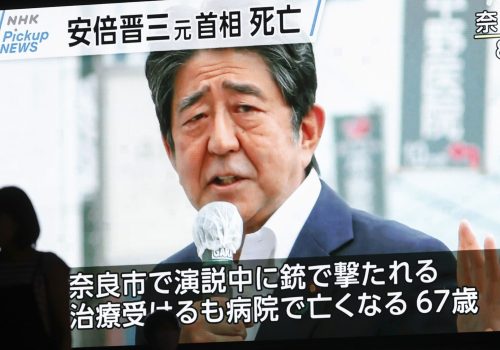

By the time Abe was murdered last month, he had not achieved all his goals for transforming Japanese security policy, such as removing constitutional constraints on the SDF, a controversial step which is still unlikely to be realized in the near term. The SDF derives its legitimacy from a longstanding interpretation of the constitution from the 1950s—but any talk of a full-fledged “military” is enough to make most Japanese deeply uneasy.

Still, Abe’s vision for Japan’s national-security policy will likely live on in other ways.

Today, there is a growing consensus domestically that the country needs to boost its defense as dangers in the region grow more acute. One need only look at the dramatically escalating tensions around Taiwan this week: Japan said several Chinese missiles, launched during military exercises shortly after US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei, landed in its exclusive economic zone. Some of Abe’s national-security policy proposals, once considered too hawkish and provocative, are gaining acceptance by larger portions of the political elite and the general population alike because of these external security challenges.

China’s rapid expansion of its military capabilities, as well as its generally assertive behavior, is one major driver of this trend. Tokyo’s concerns about its giant neighbor only increased after a series of diplomatic spats in the early 2010s over a group of disputed islands, known as the Senkakus in Japan and the Diaoyus in China. Since then, Chinese military and paramilitary activities near those islands have increased significantly. If tensions between China and Taiwan—which is only about seventy miles from Japan’s westernmost island of Yonaguni—continue increasing at the current pace, it will surely fuel even more serious concerns in Tokyo.

Meanwhile, nearby North Korea has continued improving its nuclear and missile arsenals. The country has conducted more than one hundred missile tests in recent years—two of which flew over Japan in 2017, prompting the Japanese government to alert residents. More recently, Russia’s February invasion of Ukraine compelled Japan to forsake the softer approach it took after Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and swiftly impose economic and travel sanctions. This unusual move reflected the government’s concern about revisionist forces trying to change the status quo through military might—a sentiment shared by the Japanese public, judging from its strong support for the government’s action.

The Ukraine war has strengthened support in Japan for an increase in defense spending, which was one of Abe’s national-security goals. Before his assassination, he had advocated for doubling Japan’s defense budget from the current 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) to 2 percent over a five-year period—which would make Japan the third-largest defense spender in the world—arguing that a country that does not defend itself will not receive assistance from others in times of trouble. The 2 percent defense-spending goal mirrors that of NATO member countries, and would be a major departure for Japan, which established the 1 percent cap in 1976 to signal that it is exclusively focused on self-defense. (That threshold has technically been breached several times, but it has long remained an informal guideline.) While Prime Minister Fumio Kishida plans to increase defense spending, it remains to be seen whether his government will reach Abe’s target.

Thanks to a heightened threat perception among the Japanese public, the government has also inched closer to collecting the political capital needed for the SDF to acquire the capability to attack enemy missile bases that threaten the homeland. Also endorsed by Abe, this step is controversial because it would exceed what Japan has traditionally considered necessary to defend itself. Some say it would violate the national policy of maintaining the minimum force necessary for self-defense. But proponents argue that it would enhance deterrence at a time when Japan faces missile threats from both North Korea and China.

Other ambitious national-security goals set by Abe—who stepped down as prime minister in 2020 but remained influential—are widely considered too extreme.

Most prominent is a dramatic revision of Article 9 of Japan’s Constitution, which prohibits the country from engaging in war and maintaining a full-fledged military. Over the years, Abe and his ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had dialed back their earlier ideas about ways to revise Article 9, due to political and public resistance. The current proposal adds a clause that legally recognizes the SDF—which maintains 250,000 troops but is still considered by some as unconstitutional because of the broader ban on a “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential.” The proposal would effectively legitimize the status quo, but would not allow the SDF to expand its missions beyond the “exclusively defense-oriented” policy. Japan would still be unable to acquire robust offensive military capabilities, such as intercontinental ballistic missiles and strategic bombers.

But the success of even this relatively limited revision is not guaranteed. Any change in the constitution requires support from two-thirds of both houses of Japan’s parliament, as well as a majority in a national referendum. While enough lawmakers are open to a constitutional revision, not all of them want to change Article 9; and for its part, the Japanese public appears divided over the change. The idea of legally recognizing the SDF is gaining ground, however, and further tensions in the region—such as a new conflict across the Taiwan Strait—could move public opinion toward a revision.

Another area where a major change is unlikely in the near term is Japan’s nuclear-weapons policy. The country currently relies on a US commitment to use American nuclear weapons to deter and, if necessary, defeat an attack on Japan. Before his death, Abe called for a debate on a new nuclear-sharing arrangement with the United States similar to the one Washington has with NATO (under which the United States deploys its nuclear weapons to some NATO countries) But Kishida flatly rejected the idea, citing Japan’s longstanding commitment to its three non-nuclear principles: not possessing, producing, or allowing nuclear weapons on its soil.

It remains to be seen whether Japanese attitudes toward any of these issues change. Adjustments in Japanese assessments of the country’s security environment, ranging from increased threats in the region to anxiety over the credibility of extended US nuclear deterrence, could shift Tokyo’s strategic trajectory once again. But even through these smaller steps, it’s clear that Abe’s legacy is still guiding Japanese defense policy—and could continue to do so for some time to come.

Naoko Aoki is a nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security’s Asia Security Initiative.

Further reading

Tue, Oct 5, 2021

Kishidanomics: Investing in Japan’s green, digital future

New Atlanticist By

Newly minted Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is hoping to kickstart a "virtuous cycle of growth" with public and private investment.

Fri, Jul 8, 2022

Shinzo Abe’s murder has shocked the world. What legacy will he leave behind?

New Atlanticist By

Experts from the Council’s Asia Security Initiative weigh in on what Abe’s death means for Japan’s future.

Mon, Jul 18, 2022

Dispatches from Taiwan: Follow an Atlantic Council delegation as it visits the island

New Atlanticist By

The high-level team delivers its insights, analysis, and reporting from the ground.

Image: Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force ships are pictured conducting drills with NATO in the Mediterranean Sea on June 15, 2022. Photo by EYEPRESS via Reuters Connect