Kishidanomics: Investing in Japan’s green, digital future

Japan’s Nikkei and Topix stock indices have hit multi-decade highs in recent weeks, with investors bullish on the progress of a swifter COVID-19 vaccination rollout across Japan, and exuberant about the prospects for a stronger economic recovery amidst political change. As former Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida of the Liberal Democratic Party settles into his new post as prime minister—and likely remains as such after a general election later this year—investors are responding positively to the consensus that he represents a “safe pair of hands” for the country.

By setting out key policy priorities including a “free and open Indo-Pacific” and a renewed effort to reverse the declining birth rate, as well as by actioning policies to boost innovation and investment in renewable energy, Kishida presents an element of continuity with previous administrations. This semblance of stability provides a welcome backdrop for tackling the immediate health and economic crises wrought by COVID-19, as well as for addressing longer-term structural issues such as advancing the empowerment of women and courting foreign capital and talent to support Japan’s future.

Looking beyond equity markets, the prospects for investing in a green and digital Japan can present significant opportunities for real-estate, infrastructure, and private-equity investors, as well as for possible long-term profit allocation for corporations from across the globe. In turn, such investments have the potential to create a “virtuous cycle,” in Kishida’s words, in supporting Japan’s future economic dynamism.

Business as usual at the BoJ

Looking beyond the recent equity rally, it is important to note that Japan has attracted capital from foreign investors in real estate and private equity throughout the troughs of the pandemic. Several factors have underpinned this magnetism of sticky capital and are likely to endure beyond the changes in leadership.

Throughout the crisis, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has maintained an especially accommodative monetary policy, prioritizing the support of financing activity, especially for firms. One might argue that continuity of policy at the central bank is also a critical factor for foreign investors stepping up allocations to Japan (the term of current governor Hirohito Kuroda is set to expire in 2023). In addition to ultra-loose monetary policy, bountiful fiscal relief measures—combined with a rigid labor structure and sizeable cash reserves on behalf of many firms—have also contributed to Japan having the lowest unemployment rate of the G7 economies throughout the pandemic.

Lured by low (and sometimes negative) interest rates, a stable macroeconomic environment, and bullish prospects for long-term demand, foreign real-estate investors represented more than 30 percent in value terms of all property transactions in Japan in 2020. Boasting comparatively high rates of return in recent years, global private-equity companies also have a record amount of dry powder (unallocated capital) to invest in Japan. Some of the world’s largest investment houses are bolstering their teams on the ground, in anticipation of the ability to capitalize on potential changes in the Japanese economy and society wrought by COVID-19.

Kishida has vowed to continue supporting the economy in the wake of the pandemic with “tens of trillions of yen” worth of stimulus measures, designated to support a “virtuous cycle of growth.” While there has been concern over untapped stimulus in the previous administration, it’s important to consider the ways in which government support and policy might spur key investing themes, including green, digital, and the skills revolution.

Greening Japan

With the change in leadership, Japan’s robust goal of achieving net zero carbon emissions by 2050 still seems to be on the table. As part of its decarbonization strategy, the previous government had advanced timelines to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 46 percent in 2030 (from 2019 levels), with robust targets set for renewable energy, which is slated to become the main source of power in Japan by 2030.

Kishida has highlighted a role for renewables, among other sources, in Japan’s energy mix. It is important to note that Japan ranks third in the world in total installed solar capacity—a remarkable achievement, considering that with the country’s mountainous terrain, only 30 percent of its land is flat. Given the current saturation level of solar power, the development of offshore wind might become a major component of its green growth strategy, and foreign investors have a natural role to play in building out this capacity.

A net importer of oil and natural gas, Japan has long pioneered the exploration of alternative forms of energy, including ammonia, methane hydrate, and submarine hydrothermal deposits. In their push toward carbon neutrality, officials have encouraged the cultivation of alternative sources of energy such as rare-earth mud, as well as importing hydrogen through newly constructed carbon-neutral ports.

Apart from government support, further incentives for investing in greening Japan emerge from the rich collaboration among leading universities, research centers, and the private sector in fostering an ecosystem for innovation. As demonstrated below, Japan leads the world in the number of patents in renewable energy—far exceeding the United States in the number of patents for solar energy, as well as for fuel-cell technology.

Operating at the intersection of the energy transition, mobility, and technology, one of the world’s leading companies has been engaged in developing solid-state batteries and has teamed up with a Japanese university to build out next generation battery technology. This is likely to be supported by Kishida’s proposition to expand investments into science and innovation in universities. He has also pointed to the potential to create a “digital garden city state” and to advance high-tech investments in smart farming.

Digital dreams

Although Japan is a frontrunner in developing renewable energy patents and has posted notable achievements in energy storage, some commentators have pointed to the country’s comparatively lagging stance in digital innovation and the fourth industrial revolution.

To reverse what one minister called a “digital defeat,” the Suga administration established a new digital agency last month to fully accelerate and launch digital development both within the government and across the country. Even as Japan awaits a new cabinet—and hence a potential change in leadership of the digital agency—the important thing to note is that change is already well underway.

Notably for global real-estate and infrastructure investors, a focus on digital inclusion might naturally entail an expansion of 5G across Japan’s regions. While government officials have acknowledged the benefits of teleworking, the dissemination of 5G networks across the country is likely to remain a priority and research and development into “beyond 5G” might also be encouraged. In addition to expanding the reach of telecoms networks, officials might also focus their attention on building out additional data centers (DCs), as the majority are located mostly around the Tokyo metropolitan area. This would spur a natural opportunity for real estate investors in data centers across the globe.

Investing in the skills revolution

With a focus on an inclusive economic recovery—and an eye toward addressing socio-economic disparities—Kishida is dedicated to reversing the potential for divisions within society. One way this might happen is through what has been called “growth-friendly fiscal policy,” or using the tax system to promote digital and skills investment by companies. In such a way, the government might collaborate with the private sector in a skills revolution, in mutual support of investing in skills for the future. Indeed, Japanese officials have recently highlighted the importance of cultivating a human capital base equipped to navigate changes within the new economy, including upskilling, reskilling, and vocational training—or what has been referred to as “recurrent education.”

In addition to addressing longer-term structural issues that have plagued the Japanese economy—such as flatlining productivity per worker—this bid to cement a “human new deal” via public-private partnerships presents a natural opportunity for global education technology (ed tech) investors. It also provides an opportunity for multinational corporations to proactively address skills shortages within their own organizations, thereby also potentially fulfilling growing mandates of social responsibility and the “S” component of ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria.

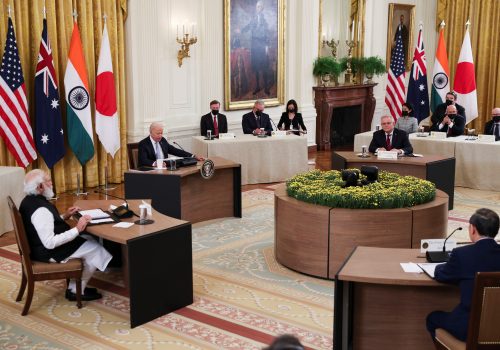

A changing Indo-Pacific

Kishida has designated a “free and open Indo-Pacific” as one of his key policy priorities, marking a key element of continuity with the Suga administration. Consistent with recent hawkish statements from Japan’s Defense Ministry, officials acknowledge a changing “security environment around Japan,” which is “becoming increasingly severe.”

This approach might entail solidifying economic and trade relationships via the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the World Trade Organization, as well as assuming leadership roles in e-commerce regulations, and the United Nations Climate Change Conference. Naturally, Kishida’s pursuit of an Indo-Pacific strategy will be enhanced by his experience as Japan’s longest-serving foreign minister.

Given this shifting environment, a priority on “bolstering Japan’s economic security” is likely to continue. This might include an emphasis on building up supplies of critical material onshore, such as semiconductor chips, ships, batteries, electricity, oil, and gas. For global real-estate and infrastructure investors, this focus on onshoring may spur opportunities for investing in logistics and supply-chain enhancement, as well as for private equity and venture-capital companies scouting opportunities in advanced tech. Indeed, Japan’s pledge to jumpstart segments of its own advanced manufacturing and semiconductor industry has already caught the eye of some of the world’s largest chip fabricators.

Is ‘womenomics’ here to stay?

As another key policy priority, Kishida has also professed a desire to reverse the declining birth rate in Japan. Also consistent with previous administrations—including some successful policies from former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—a focus on “womenomics” is a central pillar of efforts to tackle long-term demographic trends. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report, which measures the status of women based on the criteria of economy, politics, health, and education, Japan ranks 120th out of 156 countries.

In considering the economic advancement of women, officials have highlighted the need to address the “M-shaped curve”—according to which, akin to other advanced economies such as the United States, women often drop out of the labor force after childbirth. Incentivizing and rewarding women to remain in the labor force is a critical component of reversing this trend. Beyond the provision of affordable childcare (a fruit of Abe’s “womenomics”), addressing the gender pay gap in Japan should rank as a top policy priority.

The role of women in Japan’s new economy might also be supported by encouraging more women in STEM education, as well as by promoting their advancement as faculty members. This could certainly be part of Kishida’s bid to increase spending on science in universities in Japan.

In terms of governance, officials have also hinted at working toward “measurable goals for the promotion of women, non-Japanese, and mid-career hires to management positions.” According to government statistics, women make up less than 12 percent of managers in the Japanese workplace and occupy only 8 percent of board seats. While change is ostensibly supported by the government, a meaningful shift might ultimately emanate from the private sector itself. The Japanese Business Federation (commonly known as the Keidanren) recently set a goal for women to comprise 30 percent of management positions by 2030 in an effort to boost Japanese competitiveness.

Given the ways in which the private sector has injected dynamism and a sense of urgency into Japan’s climate-change policies, it could also emphasize moves toward greater diversity in Japan’s corporate culture. Indeed, such a push would be a welcome move in addressing structural impediments to long-term growth.

‘Many cultures living together’

Although this G7 economy has been a magnet for foreign investment capital in real estate and private equity prior to Kishida’s election as prime minister, his administration has the potential to generate additional bright spots for investing in offshore wind assets, hydrogen, and energy storage; 5G, “beyond 5G,” and data centers; ed tech and skills investing; semiconductors and advanced tech; and even potentially advisory services related to diversity and inclusion.

As the pandemic eventually wanes, a mindset shift will be necessary to court the right balance of strategic capital to underpin sustainable growth in a green and digital Japan. In Japan, Foreign Direct Investment amounts to only 0.788 percent of GDP—about half that of the United States, and a paltry sum in contrast with that of Singapore, which currently stands at 32.2 percent. As Japanese officials have sought to attract the world’s top companies to contribute to greater economic security, there is a certain realization that Japan cannot go it alone.

In addition to the need to attract variegated sources of investment capital, the same can be said for the landscape for diverse talent and human capital. Government officials have highlighted the need to promote “international brain circulation” in order to enhance innovation in society. Given the statistically significant relationship between innovation and immigration, a domestic embrace of the concept of tabunka kyosei (or “many cultures living together”) might help unlock the potential for economic dynamism in Japan. For that to happen, policymakers should effectively communicate the types of skills gaps and labor shortages that could be addressed by appropriate immigration, as well as a clear depiction of how this fosters innovation, boosts competitiveness, and ultimately potentially enhances domestic economic security.

Although this is a tall order for the Kishida administration, Japan is not alone in attempting to strike this delicate balance. For the new prime minister to build the dynamic economy he dreams of, he will need to look beyond Japan’s shores.

Alexis Crow is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and the global head of the Geopolitical Investing practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Further reading

Image: Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida speaks at a news conference in Tokyo on October 4, 2021. Photo by Toru Hanai/Pool via Reuters.